The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex (13 page)

Read The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex Online

Authors: Stephen E. Goldstone

He pointed to his index finger.

“Could they be from my hands?

I had a wart burned off there several months ago.”

“No, you got these warts from sex.”

“Impossible.

I only have safe sex.

Always a condom.

You can’t get it with a condom, can you?”

In the AIDS era, most guys are so worried about HIV that they forget about all the other viral sexually transmitted diseases.

Although the list is long, the most common viral STDs include herpes, condyloma, and molluscum.

(No, it’s not something you’d order at a raw bar.

) I have included hepatitis in this chapter because within the gay community, this disease is often spread through sexual contact.

As we saw in

Chapter 3

, most STDs are far more prevalent than AIDS and don’t require ejaculation or even penetration to spread.

Viral STDs are no exception, but it gets worse; the condom you so faithfully wear for penetration may not protect you.

If your partner has been rubbing his penis

against your butt or groin, he can easily pass a virus.

You say it couldn’t happen because you make him wear a condom even during foreplay.

Don’t forget about his scrotum, pubic hair, and base of his shaft, areas not covered by the condom.

He can carry viruses there and give them to you.

And once you catch one of these nasty viruses, you can have it for life.

This doesn’t mean you are doomed to a life of pain and unsightly blisters.

On the contrary, viral STDs are typified by recurring outbreaks between quiet periods.

These viruses hide within your cells, safe from marauding antibodies, white blood cells, and medications.

A virus is the simplest biological form—a segment of genetic material tightly wrapped inside a protein coat.

Unable to reproduce on its own, a virus must invade a living cell to multiply.

Once safe inside, the virus commandeers the cell’s reproductive machinery and new viruses are made.

When a virus is dormant in a cell, its genetic material is still present but idle until it receives some unknown biological stimulus to reproduce again.

Then the cells are turned into factories making copies of the virus.

New viruses break out of the cells (sometimes but not always destroying the cell in the process) and move to infect other cells—in your body or in an unsuspecting partner!

Each viral outbreak sends your immune system into overdrive, churning out antibodies and T-cells that attack viruses.

Men with AIDS may not have immune systems capable of producing enough T-cells to kill the virus.

Fortunately, various medications such as acyclovir (Zovirax) help immune systems by preventing viral reproduction and are available by prescription.

Since there is no simple way to rid yourself of many of the viral STDs, what’s a sexually active gay man to do?

The answer is simple:

Prevent infection in the first place.

But prevention is a two-sided responsibility.

You must recognize

signs of infection in your partner (see

Chapter 10

), and you also must recognize your own symptoms.

It is much harder to transmit dormant virus, so the quicker you get treated, the less chance there is for you to pass the virus on to an unsuspecting partner.

Herpes was

en vogue

in the late 1970s and early 1980s, achieving a certain cachet thanks to a flurry of media attention when rates of infection skyrocketed.

Trendy magazines and news programs carried frequent stories while dating services sprang up to help infected individuals find each other.

Although the media glare has definitely dimmed, infection rates have not.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that almost half a million new cases of genital herpes appear each year and that as many as 30 million Americans are infected.

When all is said and done, one troubling fact remains:

Once you have herpes, you have it for life.

For most of us, the word “herpes” conjures images of painful sores in sensitive spots, but herpes actually refers to a large group of viruses containing more than eighty subtypes.

Most everyone has had a prior run-in with these common viruses—remember the chicken pox?

You got that thanks to herpes zoster.

A different type of herpes virus known as HHV-8 probably causes Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS.

What we typically think of as a herpes infection is caused by two different types of the herpes simplex virus:

herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2).

(Quite ingenious, isn’t it?

) It had been thought that HSV-1 caused infections above the belt line (most often on your mouth and lips) while HSV-2 caused them below the belt line.

We now know this is not entirely the case; HSV-2

can turn up in your mouth and, conversely, HSV-1 can infect your genitals.

The herpes simplex virus attacks only humans and is usually passed via direct sexual contact.

Although doctors report sporadic transmission after close physical contact (particularly between patients and healthcare workers), unless you are a masseur, you can’t get it from anything other than sex.

The fact that herpes can infect your oral cavity is especially important if you enjoy fellatio.

A condom would protect you, but most men don’t use one unless ejaculation is planned.

Just as you can catch herpes by sucking an infected penis—even if the herpes infection isn’t currently active—the converse is also true:

Your partner can spread the virus from his mouth to your penis.

Herpes passes to your anorectal region during rimming or unprotected rubbing of an infected partner’s penis against your buttocks.

Penetration is not necessary.

Again, a condom would be protective, but most men use condoms only for penetration.

Once a herpes virus lands on your body, it invades the skin.

You can’t see the virus at this early stage, but you might notice symptoms that you associate with any viral illness, such as a low-grade fever, weakness, and an achy feeling.

Within a week a burning sensation (occasionally quite painful) begins in the skin, followed, a day or two later, by a cluster of small, clear blisters.

(See

Figure 4.

1

.

) Pain intensifies as blisters develop, and at this point you become highly contagious.

You spread the virus not only to sexual partners but also to other parts of your own body (eyes, fingers, etc.

).

Do not touch your blisters, but if you do, wash your hands thoroughly with an antibacterial soap.

As with chicken pox, blisters typically burst in three to five days, leaving shallow pink ulcers that crust over.

Once crusting is complete, healing without scarring occurs.

The entire cycle usually lasts two weeks.

Herpes then enters a “latent phase” during which the virus goes into hiding.

Although its exact location is unknown, doctors suspect the viruses hide in large sensory nerves around your sacrum.

The virus remains dormant until something triggers it to reproduce and travel down the nerves to your anogenital region, where the cycle begins anew.

Unfortunately, we do not know what triggers this change from latency to attack, and the length of time between outbreaks is completely unpredictable.

Clearly, men with compromised immune systems (those with AIDS or on chemotherapy) are predisposed to recurrent attacks.

Cancer or severe infections can precipitate an attack, as can local trauma to your anogenital region (especially sunburn, so keep those bathing suits on).

Periods of intense emotional stress also have been associated with herpes outbreaks.

Whatever the cause, most people experience another attack within a year after their initial infection.

Expect four to five attacks in your first year, but some attacks can be so mild that you don’t even know you’re having one.

Subsequent attacks are usually shorter, and healing occurs within one week.

The good news is that over time, the frequency of outbreaks diminishes.

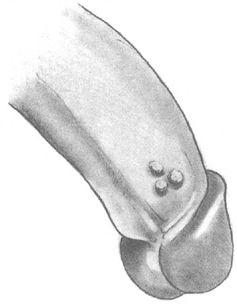

Figure 4.

1:

Herpes Blisters

On the penis, herpes blisters occur anywhere, from the head and shaft to under your foreskin.

(See

Figure 4.

1

.

) In your anal area, look for blisters on the surrounding skin or within the anus itself.

If your anal canal or rectum is involved, symptoms typically include bleeding and intense pain during bowel movements.

A bloody mucus discharge even without the passage of stool is common.

The colon lining can become so inflamed that many times a herpes outbreak is misdiagnosed as colitis unless you are honest with your doctor and admit to having had anal sex.

It is often difficult for physicians to diagnose a herpes infection in your mouth, because blisters hide on the roof of your mouth or between your lips and gums.

Symptoms are similar to what you would expect from any typical sore throat, with pain on swallowing, redness, and swollen lymph nodes (glands) in your neck.

Because the blisters are tiny, your doctor can easily miss them.

Unless you mention having had oral sex, most physicians won’t even think of herpes and will dismiss you with instructions to take throat lozenges.

When herpes recurs in your mouth, it is usually at the edge of your lip and commonly is called a fever blister or cold sore.

No matter how benign that name sounds, you still have a herpes infection that is highly contagious and easily passed to others.

To make the diagnosis of a herpes infection, doctors rely on a positive viral culture from your blister.

Although this type of culture is done with a cotton swab, it differs markedly from typical bacterial cultures you may be used to.

(Remember the strep test when your doctor rammed the

long stick down your throat until you gagged?

) A viral culture requires a different medium in which to grow, so if your doctor just performs a standard bacterial culture he or she will not find the herpes.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that within two weeks your symptoms disappear on their own.

This pattern is typical of any run-of-the-mill sore throat or nonspecific colitis, so the correct diagnosis is never made.

Why is it a problem if your herpes infection is missed, when it resolves on its own?

First and foremost, failure to make the diagnosis allows you to unwittingly pass herpes on to other partners.

Another advantage of making a timely diagnosis is that medications abort your attack.

In an untreated herpes outbreak, your immune system attacks the virus through a combination of antibodies and T-cells.

Because your first episode sensitizes your immune system, subsequent attacks are shorter.

Herpes antibodies can be detected in your blood and indicate that you’ve had a prior run-in with the virus.

Patients with AIDS and low T-cell counts are prone to frequent and more severe recurrences.

Medications such as acyclovir (Zovirax) and its derivatives, valacyclovir (Valtrex) and famciclovir (Famvir), are available in tablet form by prescription.

These drugs work to stop virus reproduction and typically shorten an attack.

The standard dose of acyclovir for acute herpes outbreaks is either 200 milligrams (mg) five times a day or 400 mg three times a day for ten days.

The latter dose is probably easier to manage and just as effective.

Although valacyclovir is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in immunocompromised (AIDS) patients, most doctors find it effective.

For first-time infections, the dose of valacyclovir is 1 gram twice a day for ten days, but with recurrent infections it decreases to 500 mg twice a day for five days.

The recommended dose for famciclovir for

acute attacks is 500 mg twice a day for seven days.

Some physicians also recommend acyclovir cream in combination with pills, but many medical authorities feel that that provides little or no added benefit.

These medications are relatively safe with few side effects and should be started at the first sign of an attack.