The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War (41 page)

Read The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War Online

Authors: Daniel Stashower

When Lincoln emerged, Judd would report, he carried a shawl draped over his arm. The shawl, according to Lamon, would help to mask Lincoln’s features as he emerged from the hotel. Curtin led the group toward the side entrance of the hotel, where a carriage waited. As they made their way along the corridor, Judd whispered to Lamon, “As soon as Mr. Lincoln is in the carriage, drive off. The crowd must not be allowed to identify him.”

Reaching the side door, Lamon climbed into the carriage first, then turned to help Lincoln and Curtin. At this, Judd stepped forward, steeling himself for the first of the evening’s many deceits. “Colonel Sumner was following close after Mr. Lincoln,” Judd recalled. “I put my hand gently on his shoulder. He turned round to see what was wanted, and before I had time to explain the carriage was off.” Sumner, left behind on the pavement like a dim-witted schoolboy, was outraged. “A madder man you never saw,” said Judd. One account has it that the old soldier wept with indignation.

Judd apologized in heartfelt terms. “When we get to Washington,” he said, “Mr. Lincoln shall determine what apology is due you.” Privately, Judd was relieved. The first phase of Pinkerton’s scheme had gone according to plan.

* * *

TO THE END OF HIS LIFE,

Pinkerton would enjoy telling a story concerning two newspapermen—possibly Joseph Howard of the

New York Times

and Simon Hanscom of the

New York Herald

—who were singled out for special treatment that evening. These two “knights of the quill,” Pinkerton recalled, were preparing to attend a scheduled evening reception for Lincoln when “a gentlemanly individual, well-known to me” appeared at the door of their hotel room. “The visitor quickly informed the gentlemen that Mr. Lincoln had left the city and was now flying over the road in the direction of Washington,” Pinkerton related. The reporters, startled by this unexpected news, “hastily arose, and, grasping their hats, started for the door,” eager to get this bulletin onto the telegraph wires. “Their visitor, however, was too quick for them,” Pinkerton noted with satisfaction, “and standing before the door with a revolver in each hand, he addressed them: ‘You cannot leave this room, gentlemen, without my permission!’”

A heated exchange followed: “‘What does this mean?’ inquired one of the surprised gentlemen, blinking through his spectacles.”

“‘It means that you cannot leave this room until the safety of Mr. Lincoln justifies it,’ calmly replied the other.”

Before the journalists could protest further, the unnamed gentleman struck a deal. If they would bide their time until morning, he would “make matters interesting,” with a full account of the “flank movement on the Baltimoreans.”

“Their indignation and fright subsided at once,” Pinkerton related, “and they quietly sat down. Refreshments were sent for, and soon the nimble pencils of the reporters were rapidly jotting down as much of the information as was advisable to be made public at that time.”

Pinkerton’s account bears the stamp of wishful thinking, but it is at least partially true. Years later, Joseph Howard of the

Times

would admit that he had been pulled aside that night and notified of what was transpiring. “The information had been given under an injunction of secrecy,” he said. “We were bound by honor not to attempt to use it until the morning, and did not.” Howard did, however, file a seemingly innocuous dispatch of earlier events in Harrisburg, which appeared the following morning. Seen in retrospect, the article appears freighted with secret knowledge of Lincoln’s unexplained absence that evening: “Mr. Lincoln being physically prostrated by hard labor, did not give the anticipated reception, but like a prudent man went to bed early,” Howard wrote. “We anticipate an exciting time today, and praying that it may prove an agreeable excitement, having a prosperous termination, I close.”

Howard’s next dispatch would be the most sensational of his career.

PART THREE

THE MARTYR

and

THE SCAPEGOAT

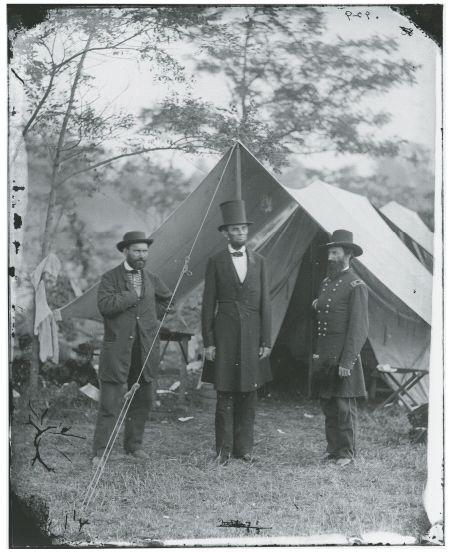

Allan Pinkerton and Abraham Lincoln, with General John A. McClernand, at Antietam, Maryland, October 3, 1862.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

THE FLIGHT OF ABRAHAM

Uncle Abe had gone to bed,

The night was dark and rainy

A laurelled night-cap on his head

Way down in Pennsylvany

They went and got a special train

At midnight’s solemn hour,

And in a cloak and Scottish plaid shawl,

He dodged from the Slave-Power

Lanky Lincoln came to town

In night and wind, and rain, sir

Wrapped in a military cloak

Upon a special train, sir

—revised lyrics for “Yankee Doodle,” which appeared in several Democratic newspapers, February 1861

AT WILLARD’S HOTEL IN WASHINGTON

the following morning—Saturday, February 23—the ongoing Peace Convention was scheduled to reconvene at 10:00

A.M.

Lucius Chittenden, the Vermont delegate whose midnight run to Baltimore one week earlier had left him convinced of a looming threat, noted an atmosphere of mounting excitement among his colleagues. “There were a few Republicans whose faces shone as they greeted each other,” he reported, because they shared a momentous secret.

“Members were not particular about the position of their seats,” Chittenden recalled, and that morning he happened to find himself squeezed between two outspoken Southerners: James A. Seddon, a former congressman from Virginia, and Missouri senator Waldo P. Johnson. Though Chittenden could not have known it at the time, both men would soon be serving the Confederacy—Johnson as an infantry colonel, and Seddon as secretary of war. That morning, however, both men had ostensibly gathered “to agree upon terms of compromise and peace.” Moments after the morning session was gaveled to order, a note was handed to Seddon. “Mr. Seddon glanced at it,” Chittenden wrote, “and passed it before me to Mr. Johnson, so near to my face that, without closing my eyes, I could not avoid reading it.” The note confirmed what Chittenden and other Republicans already knew. “The words written upon it were: Lincoln is in this hotel!”

As Chittenden recalled the scene, Johnson “was startled as if by a shock of electricity” as he read the note. In the excitement, Johnson “must have forgotten himself completely,” Chittenden continued. The Southern senator looked across at Seddon and blurted out, “How the devil did he get through Baltimore?”

With a look of “utter contempt” for the indiscretion, Seddon silenced his impulsive colleague with a sharp reply. “What,” he growled, “would prevent his passing through Baltimore?”

“There was no reply,” Chittenden noted, “but the occurrence left the impression on one mind that the preparations to receive Mr. Lincoln in Baltimore were known to some who were neither Italian assassins nor Baltimore Plug-Uglies.” For the moment, Chittenden did not have time to ponder the implications of what he had overheard. As the news of Lincoln’s unexpected arrival spread through the hall, the rising din of excited voices drowned out the repeated hammering of the speaker’s gavel. It would be some time before the conference could resume.

* * *

IN BALTIMORE AT NEARLY THE SAME MOMENT,

Otis K. Hillard fastened a palmetto cockade to his vest, a mark of the role he expected to play at the moment of Lincoln’s arrival. Hillard had heard a rumor that Lincoln had already slipped through the city unannounced, but he did not believe it. He declared that he would carry through with his orders to be present at the Calvert Street Station at 12:30, when Lincoln’s train was scheduled to arrive from Harrisburg. He asked his new friend Harry Davies to join him as he took up his assigned position.

As the two men made their way to Calvert Street, Davies noted that the streets were heaving with “some ten or fifteen thousand people,” all of them pushing and jostling their way toward the depot. Hillard pointed out several members of the National Volunteers along the way, and stopped to speak with several of them. The excitement of the hour made Hillard far more talkative than he had been at any point since Davies’s arrival in Baltimore. He swept his hand in the direction of a row of men standing in close formation. They were National Volunteers, too, he said, converging on the route that Lincoln was likely to take along Calvert Street. At Monument Square, site of a towering marble column commemorating the War of 1812’s Battle of Baltimore, an especially large contingent had gathered. Hillard explained that “if by any mishap Lincoln should reach that point alive,” having somehow emerged safely from the depot, he would get no farther than Monument Square, where the Volunteers would “rush en-mass” and strike him down. In the confusion, Hillard insisted, “it would be impossible for any outsider to tell who did the deed,” and he boasted, “that from his position he would have the first shot.”

The police, Hillard claimed, would present no obstacle. He told Davies that it was “so arranged, or was so understood by him, that the police were not to interfere.” Instead, the officers would do just enough to give the appearance of doing their duty. Even if they did intervene, Hillard said, what could they do against a force of thousands? Besides, he noted with obvious satisfaction, their leader, Marshal Kane, was nowhere to be seen. “He knows his business,” Hillard said.

By noon, as the rumors of Lincoln’s safe arrival in Washington gathered force, cracks began to appear in Hillard’s bravado. “Could it be true?” he asked Davies. If so, “how in hell had it leaked out that Lincoln was to be mobbed in Baltimore?” Lincoln must somehow have been warned, he told Davies, “or he would not have gone through as he did.”

At 12:30, the scheduled arrival time of the Lincoln Special, Hillard began to panic. Had he and his colleagues been found out? Was he about to be arrested? Davies could not resist a gibe. “I told him he belonged to a damned nice set [if] seven thousand men could not keep track of one man.” Hillard admitted that he could not explain how Lincoln could have given them the slip. He claimed that “they had men on the look out all the time,” watching for any change of plan. Even now, Hillard clung to a hope that the rumors were false. The train was simply running late, he said. Lincoln would appear at any moment. But, he insisted, if “Lincoln got away” somehow, there would be a reckoning. It would be a signal that “the ball had commenced now for certain,” and a direct attack on Washington would follow.

By 1:00

P.M.

, however, Hillard had spiraled into a state of despair. Special editions of the newspapers were now flowing into the streets. The rumors could no longer be denied: Lincoln was safe in Washington. William Louis Schley, one of the few Baltimore Republicans in the crowd that day, wrote to Lincoln to describe the scene: “[Y]ou may judge the disappointment at the announcement of your ‘passage’ through

unseen, unnoticed and unknown

—it fell like a thunder clap upon the Community.” Schley went on to compliment Lincoln on a wise decision: “By your course you have saved

bloodshed and a mob.

”

Hillard still hoped the day was not lost. Leaving Davies at the depot, he went off in search of his fellow conspirators. By the time Davies caught up with him at his hotel later that afternoon, Hillard was much the worse for drink and “unusually noisy” as a result. “I told him to sit down, or lay down, and keep quiet,” Davies said, but Hillard could not keep still. He paced back and forth, waving his hands in the air as he cautioned Davies to “be careful and not breathe a word.” It was terrifying, Hillard admitted, to think that there might well be a spy in their midst. The Pinkerton man said nothing.

In spite of these fears, Hillard grew “quite merry” as the effects of the day’s excitement and heavy drinking took hold. He insisted that a new plan was already being laid. Five thousand dollars had already been raised to buy arms, he told Davies, and soon there would be fifty men actively seeking a chance to kill Lincoln. “From what I could gather from him,” Davies reported, “Washington City appeared now to be the principal point for action by those in the plot to take Lincoln’s life.”

Whatever happened next, Hillard claimed, at least one thing had been accomplished that day: Lincoln had disgraced himself in the eyes of both North and South. “It is a good thing that Lincoln passed through here as he did, because it will change the feeling of the Union men,” Hillard declared. “They will think him a coward, and it will help our cause.”