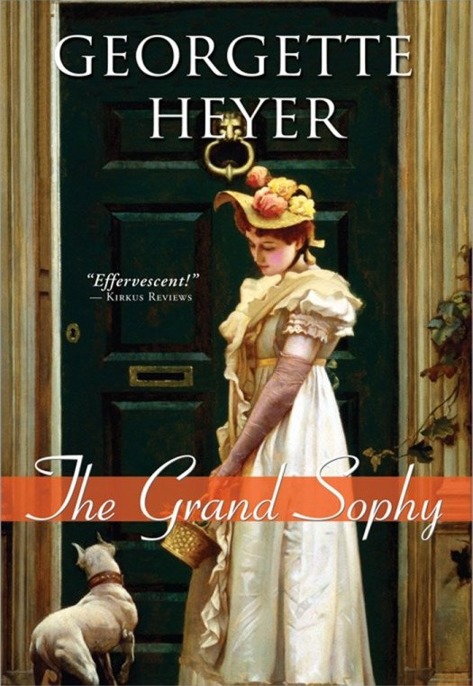

The Grand Sophy

Authors: Georgette Heyer

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Historical, #General

The Grand Sophy

Georgette Heyer

1950

I

THE BUTLER, recognizing her ladyship’s only surviving brother at a glance, as he afterward informed his less percipient subordinates, favored Sir Horace with a low bow, and took it upon himself to say that my lady, although not at home to less nearly connected persons, would be happy to see him. Sir Horace, unimpressed by this condescension, handed his caped greatcoat to one footman, his hat and cane to the other, tossed his gloves onto the marble-topped table, and said that he had no doubt of that, and how was Dassett keeping these days? The butler, torn between gratification at having his name remembered and disapproval of Sir Horace’s free and easy ways, said that he was as well as could be expected, and happy (if he might venture to say so) to see Sir Horace looking not a day older than when he had last had the pleasure of announcing him to her ladyship. He then led the way, in a very stately manner, up the imposing stairway to the Blue Saloon, where Lady Ombersley was dozing gently on a sofa by the fire, a Paisley shawl spread over her feet, and her cap decidedly askew. Mr. Dassett, observing these details, coughed, and made his announcement in commanding accents: “Sir Horace Stanton-Lacy, my lady!”

Lady Ombersley awoke with a start, stared for an uncomprehending moment, made an ineffective clutch at her cap, and uttered a faint shriek. “Horace!”

“Hallo, Lizzie, how are you?” said Sir Horace, walking across the room, and bestowing an invigorating buffet upon her shoulder.

“Good heavens, what a fright you gave me!” exclaimed her ladyship, uncorking the vinaigrette which was never out of her reach.

The butler, having tolerantly observed these transports, closed the door upon the reunited brother and sister, and went away to disclose to his underlings that Sir Horace was a gentleman as lived much abroad, being, as he was informed, employed by the government on diplomatic business too delicate for their understanding.

The diplomatist, meanwhile, warming his coattails by the fire, refreshed himself with a pinch of snuff and told his sister that she was putting on weight. “Not growing any younger, either of us,” he added handsomely. “Not but what I can give you five years, Lizzie, unless my memory’s at fault, which I don’t think it is.”

There was a large gilded mirror on the wall opposite the fireplace, and as he spoke Sir Horace allowed his gaze to rest upon his own image, not in a conceited spirit, but with critical approval. His forty-five years had treated him kindly. If his outline had thickened a little his height, which was well above six feet, made a slight portliness negligible. He was a very fine figure of a man, and had, besides a large and well-proportioned frame, a handsome countenance, topped by luxuriant brown locks as yet unmarred by silver streaks. He was always dressed with elegance, but was far too wise a man to adopt such extravagances of fashion, as could only show up the imperfections of a middle-aged figure. “Take a look at poor Prinny!” said Sir Horace to less discriminating cronies. “He’s a lesson to us all!”

His sister accepted the implied criticism unresentfully. Twenty-seven years of wedlock had left their mark upon her; and the dutiful presentation to her erratic and far from grateful spouse of eight pledges of her affection had long since destroyed any pretensions to beauty in her. Her health was indifferent, her disposition compliant, and she was fond of saying that when one was a grandmother it was time to be done with thinking of one’s appearance.

“How’s Ombersley?” asked Sir Horace, with more civility than interest.

“He feels his gout a little, but considering everything he is remarkably well,” she responded.

Sir Horace took a mere figure of speech in an undesirably literal spirit, saying, with a nod, “Always did drink too much.

Still, he must be going on for sixty now, and I don’t suppose you have so much of the other trouble, do you?”

“No, no!” said his sister hastily. Lord Ombersley’s infidelities, though mortifying when conducted, as they too often were, in the full glare of publicity, had never greatly troubled her, but she had no desire to discuss them with her outspoken relative, and gave the conversation an abrupt turn by asking where he had come from.

“Lisbon,” he replied, taking another pinch of snuff.

Lady Ombersley was vaguely surprised. It was now two years since the close of the long Peninsular War, and she rather thought that when last heard of Sir Horace had been in Vienna, no doubt taking mysterious part in the Congress, which had been so rudely interrupted by the escape of that dreadful Monster from Elba. “Oh!” she said, a little blankly. “Of course, you have a house there! I was forgetting! And how is dear Sophia?”

“As a matter of fact,” said Sir Horace, shutting his snuffbox, and restoring it to his pocket, “it’s about Sophy that I’ve come to see you.”

Sir Horace had been a widower for fifteen years, during which period he had neither requested his sister’s help in rearing his daughter nor paid the least heed to her unsolicited advice, but at these words an uneasy feeling stole over her. She said, “Yes, Horace? Dear little Sophia! It must be four years or more since I saw her. How old is she now? I suppose she must be almost out?”

“Been out for years,” responded Sir Horace. “Never anything else, really. She’s twenty.”

“Twenty!” exclaimed Lady Ombersley. She applied her mind to arithmetic, and said, “Yes, she must be, for my own Cecilia is just turned nineteen, and I remember that your Sophia was born almost a year before. Dear me, yes! Poor Marianne! What a lovely creature she was, to be sure!”

With a slight effort Sir Horace conjured up the vision of his dead wife. “Yes, so she was,” he agreed. “One forgets, you know. Sophy’s not much like her—favors me!”

“I know what a comfort she must have been to you,” sighed Lady Ombersley. “And I’m sure, dear Horace, that nothing could be more affecting than your devotion to the child!”

“I wasn’t in the least devoted,” interrupted Sir Horace. “I shouldn’t have kept her with me if she’d been troublesome. Never was. Good little thing, Sophy!”

“Yes, my dear, no doubt, but to be dragging a little girl all over Spain and Portugal, when she would have been far better in a select school—”

“Not she! She’d have learned to be missish,” said Sir Horace cynically. “Besides, no use to prose to me now on that head—it’s too late! The thing is, Lizzie, I’m in something of a fix. I want you to take care of Sophy while I’m in South America.”

“South America?” gasped Lady Ombersley.

“Brazil. I don’t expect to be away for very long, but I can’t take my little Sophy, and I can’t leave her with Tilly because Tilly’s dead. Died in Vienna, couple of years ago. A devilish inconvenient thing to do, but I daresay she didn’t mean it.”

“Tilly?” said Lady Ombersley, all at sea.

“Lord, Elizabeth, don’t keep on repeating everything I say! Shocking bad habit! Miss Tillingham, Sophy’s governess!”

“Good heavens! Do you mean to tell me that the child has no governess now?”

“Of course she has not! She don’t need a governess. I always found plenty of chaperons for her when we were in Paris, and in Lisbon it don’t signify. But I can’t leave her alone in England.”

“Indeed, I should think not! But, my dearest Horace, though I would do anything to oblige you, I am not quite sure—”

“Nonsense!” said Sir Horace bracingly. “She’ll be a nice companion for your girl—what’s her name? Cecilia? Dear little soul, you know—not an ounce of vice in her!”

This fatherly tribute made his sister blink, and utter a faint protest. Sir Horace paid no heed to it. “What’s more, she won’t cause you any trouble,” he said. “She has her head well on her shoulders, my Sophy. I never worry about her.”

An intimate knowledge of her brother’s character made it perfectly possible for Lady Ombersley to believe this, but since she herself was blessed with much the same easygoing temperament no acid comment even rose to her lips. “I am sure she must be a dear girl,” she said. “But, you see, Horace—”

“And another thing is that it’s time we were thinking of a husband for her,” pursued Sir Horace, seating himself in a chair on the opposite side of the fireplace. “I knew I could depend on you. Dash it, you’re her aunt! My only sister, too.”

“I should be only too happy to bring her out,” said Lady Ombersley wistfully. “But the thing is I don’t think—I am rather afraid— You see, what with the really dreadful expense of presenting Cecilia last year, and dearest Maria’s wedding only a little time before that, and Hubert’s going up to Oxford, not to mention the fees at Eton for poor Theodore—”

“If it’s expense that bothers you, Lizzie, you needn’t give it a thought, for I’ll stand the nonsense. You won’t have to present her at Court—I’ll attend to all that when I come home, and if you don’t want to be put to the trouble of it then I can find some other lady to do it. What I want at this present is for her to go about with her cousins, meet the right set of people—you know the style of thing!”

“Of course I know, and as for trouble it would be no such thing! But I cannot help feeling that perhaps, perhaps it would not do! We do not entertain very much.”

“Well, with a pack of girls on your hands you ought to,” said Sir Horace bluntly.

“But, Horace, I have not got a pack of girls on my hands!” protested Lady Ombersley. “Selina is only sixteen, and Gertrude and Amabel are barely out of the nursery!”

“I see what it is,” said Sir Horace indulgently. “You’re afraid she may take the shine out of Cecilia. No, no, my dear! I daresay you’ll think she’s a very pretty girl. But Cecilia’s something quite out of the common way. Remember thinking so when I saw her last year. I was surprised, for you were never above the average yourself, Lizzie, while I always thought Ombersley a plain-looking fellow.”

His sister accepted these strictures meekly, but was quite distressed that he should suppose her capable of harboring such unhandsome thoughts about her niece. “And even if I was so odious, there is no longer the least need for such notions,” she added. “Nothing has as yet been announced, Horace, but I don’t scruple to tell you that Cecilia is about to contract a very eligible alliance.”

“That’s good,” said Sir Horace. “You’ll have leisure to look about you for a husband for Sophy. You won’t have any difficulty. She’s a taking little thing, and she’ll have a snug fortune one of these days, besides what her mother left her. No need to be afraid of her marrying to disoblige us, either. She’s a sensible girl, and she’s been about the world enough to be well up to snuff. Whom have you got for Cecilia?”

“Lord Charlbury has asked Ombersley’s permission to address her,” said his sister, swelling a little with pride.

“Charlbury, eh?” said Sir Horace. “Very well indeed, Elizabeth! I must say, I didn’t think you’d catch much of a prize, because looks aren’t everything, and from the way Ombersley was running through his fortune when I last saw him—”

“Lord Charlbury,” said Lady Ombersley a little stiffly, “is an extremely wealthy man, and, I know, has no such vulgar consideration in mind. Indeed, he told me himself that it was a case of love at first sight with him!”

“Capital!” said Sir Horace. “I should suppose him to have been hanging out for a wife for some time—thirty at least, ain’t he? But if he has a veritable tendre for the girl, so much the better! It should fix his interest with her.”

“Yes,” agreed Lady Ombersley. “And I am persuaded they will suit very well. He is everything that is amiable and obliging, his manners most gentlemanlike, his understanding decidedly superior, and his person such as must please.”

Sir Horace, who was not much interested in his niece’s affairs, said, “Well, well, he is plainly a paragon, and we must allow Cecilia to think herself fortunate to be forming such a connection! I hope you may manage as prettily for Sophy!”

“Indeed, I wish I might!” she responded, sighing. “Only it is an awkward moment, because—the thing is, you see, that I am afraid Charles may not quite like it!”

Sir Horace frowned in an effort of memory. “I thought his name was Bernard. Why shouldn’t he like it?”

“I am not speaking of Ombersley, Horace. You must remember Charles!”

“If you’re talking about that eldest boy of yours, of course I remember him! But what right has he to say anything, and why the devil should he object to my Sophy?”

“Oh, no, not to her! I am sure he could not do so! But I fear he may not like it if we are to be plunged into gaiety just now! I daresay you may not have seen the announcement of his own approaching marriage, but I should tell you that he has contracted an engagement to Miss Wraxton.”

“What, not old Brinklow’s daughter? Upon my word, Lizzie, you have been busy to some purpose! Never knew you had so much sense! Eligible, indeed! You are to be congratulated!”

“Yes,” said Lady Ombersley. “Oh, yes! Miss Wraxton is a most superior girl. I am sure she has a thousand excellent qualities. A most well-informed mind, and principles such as must command respect.”

“She sounds to me like a dead bore,” said Sir Horace frankly.

“Charles,” said Lady Ombersley, staring mournfully into the fire, “does not care for very lively girls, or—or for any extravagant folly. I own, I could wish Miss Wraxton had rather more vivacity. But you are not to regard that, Horace, for I had never the least inclination toward being a bluestocking myself, and in these days, when so many young females are wild to a fault, it is gratifying to find one who— Charles thinks Miss Wraxton’s air of grave reflection very becoming!” she ended, in rather a hurry.