The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels (7 page)

Authors: Thomas Cahill

Religion is a complex phenomenon; and the correspondences soon became more complex, requiring orders of priests and shamans for their correct interpretation and effective use. The phallic snake, which sheds its skin and also disappears for part of each year, and thus was thought to die and regenerate itself, became in many different cultures the moon’s earthly manifestation. Idols recovered from such widely distant places as the Panchan and Ngan-Yang cultures of neolithic China and the Amerindian civilization of Calchaqui show the lozenge-decorated serpent, male and female combined, symbol of dualism reintegrated and potent predictor of fertility. Another moon-creature was the spider, whose silvery, cyclical web traps its victims in an image of man’s fate, which the moon, who sways all living things, was thought to control. (To spin is to predestine; and some of the oldest words for fate, such as the Anglo-Saxon

wyrd

, come from the Indo-European verb

uert

, meaning “to turn” or “to spin.”) The bull, whose crescent horns are the very image of the sickle moon, was sacred to Nanna-Sin, who was himself “the powerful calf with strong horns,” “the young bull of the sky.” The pearl was the Moon god’s amulet, the shining little moon contained within the vulva of the oyster. In pre-Columbian Mexico the snail, which like the moon, displays and withdraws its horns, was sacred to the moon, as was in Ice Age Europe the bear, who appears and disappears with the seasons and is the ancestor of humanity. Among peoples as widely dispersed as the African Bushmen, the Samoyed, and the Chinese, a whole series of lunar figures who were missing a hand or foot (like the incomplete moon) were

characterized by their power to bring rain and subsequent fertility.

T

HE

E

VOLUTION OF

W

RITING

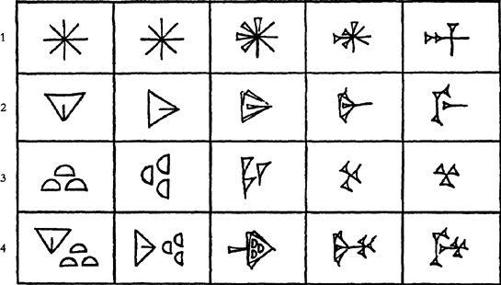

(1) The pictograph in the top row originally represents “star” but also comes to designate “god.” (2) The cleft triangle (which had an even more ancient antecedent, the lozenge or diamond shape) stands for the female genitals but also comes to designate “woman.” (3) Mountains. (4) “Mountain woman,” that is, a Semitic slave girl

.

Pictured above (from left to right) is the evolution of each sign from an original pictograph into a more easily incised symbol, shaped by the strokes of a small wedge-shaped stylus—thus cuneiform (or wedge-shaped) writing

.

In examining these correspondences that primitive man found so obvious, we post-Aristotelians are more likely to be struck by their illogic than by their appositeness. To see with the eyes of primitive society, we must abandon both our logic and our science. “The point,” writes Eliade, “of all these analogies is first of all to unite man with the rhythms

and energies of the cosmos, and then to unify the rhythms”—as in the sacred copulation rite—“fuse the centers and finally effect a leap into the transcendent,” what Eliade calls the “primal unity.” The underlying purpose of primitive theology was no different from that of any other human attempt to reach the truth: these people, our distant ancestors, were looking for knowledge that was

effective

, that could help them achieve prosperity, progeny, and the only immortality available to human beings—assurance that their seed would not die with them. And for the more mystical among them, there was the belief that this knowledge could put them in touch with something beyond themselves. Every rite has its irrational, mystical center, its acme of consecration, its moment out of time; and whether it is the transformation of the bread and wine at Mass, the whirling of the dervish, or the orgasm of Sumer, its purpose is ecstatic union, however fleeting, with transcendent reality, with the ultimate, with what is beyond mutability. For the ancients, such reality was beyond earth, beyond even the moon, beyond all becoming.

“Supra lunam sunt aeterna omnia,”

wrote

Cicero, echoing a most ancient Mediterranean belief in absolutes: “Beyond the moon are all the eternal things.”

A

century or two after the beginning of the second millennium

B.C.

, a family of Ur found wanting this static worldview of heavenly absolutes and earthly corruption. They were Terah’s family, as we read in Genesis, the first book of the Bible:

Now these are the begettings of Terah:Terah begot Avram,

1

Nahor and Haran;and Haran begot Lot.

Haran died in the living-presence of Terah his father in the land of his kindred, in Ur of the Chaldeans.

Avram and Nahor took themselves wives;

The name of Avram’s wife was Sarai,

The name of Nahor’s wife was Milcah—daughter of Haran, father of Milcah and father of Yisca.

Now Sarai was barren, she had no child.

Terah took Avram his son and Lot son of Haran, his son’s son, and Sarai his daughter-in-law, wife of Avram his son,

They set out together from Ur of the Chaldeans, to go to the land of Canaan.

But when they had come as far as Harran, they settled there.

And the days of Terah were five years and two hundred years,

then Terah died,

in Harran.

At first glance, this may strike the reader as an unimpressive narrative that, in its plainness and peculiarity (Terah, whoever he was, did not live for more than two centuries), has certain affinities with the narratives of Sumer,

if none of their mythological dash. But there are surprising dissimilarities: the careful preserving of the names and lineages of ancient characters—even of women—who were neither gods nor kings; and the importance placed on what

appear

at least to be exacting genealogical records.

Terah’s was a family of Semites, long settled at Ur, now “the land of his kindred.” His ancestors, hundreds of years earlier, had been part of the movement of wandering Semitic tribes that had overwhelmed the power of Sumer and been subsequently absorbed by its superior urban culture. The lines quoted here, a translation from the Semitic tongue called Hebrew, are found in Genesis just after the stories of human beginnings—from the Creation to the Flood. But unlike the stories that precede it, this chronicle of Terah’s family sounds not like a fairy tale but like an attempt at real historical narrative; and though, in this written form, it is probably less than three thousand years old, it is the product of an oral tradition that takes us back almost four thousand years, close to the beginning of the second millennium

B.C.

, to the period of Babylonian Sumer’s Golden Age under the aegis of

Hammurabi, the world’s first emperor.

We cannot be sure what these citizens of Ur had in mind when they set out. Probably not much. They traveled northwest along the Euphrates from Ur to Harran, a city also dedicated to the moon, a sister city of Ur and very like it in outlook—San Francisco to Ur’s New York. So their first attempt at relocation may have been only to improve their prospects, and there is some reason to believe that they

meant to settle permanently in Harran. For Avram, however, Harran was to be but a stage. What is odd about this passage is the assumption that the family’s ultimate destination is to be “the land of Canaan,” a hinterland of the Semitic tribes, who (at least in Sumerian caricature) ate their meat raw and didn’t even know how to bury their dead. No one whose family was established at Ur would have thought to leave it except for a similar city. So what we may be witnessing here is a migration in the wrong direction, a regression to simpler roots from which the urbanized Semites who had settled in Sumer had been cut off for centuries. But this peculiar migration would change the face of the earth by permanently changing the minds and hearts of human beings.

In Harran, Terah and his family struck it rich; and it was almost certainly in Harran that a voice spoke to Avram and said:

“Go-you-forth

from your land,

from your kindred,

from your father’s house,

to the land that I will let you see.

I will make a great nation of you

and will give-you-blessing

and will make your name great.

Be a blessing!

I will bless those who bless you,

he who curses you, I will damn.All the clans of the soil will find blessing through you!”

So, comments the anonymous narrator, “Avram went.” And with him went Lot, Sarai, “all their gain they had gained and the souls they had made in Harran,” that is, two extended households on the move once more. But in addition to their family members and chattel, they took their Sumerian outlook. However much of a discontinuity with the past this journey would come to represent, Avram, Sarai, and Lot, their families and slaves were people of Sumer and could no more escape the mind-set of their culture than we can escape ours. Something new is happening here; but it is happening as all things new must happen—in the midst of the old, usual, ordinary reality of what was then daily life.

“Nova ex veteris,”

runs the old Latin paradox. “The new must be born out of the old.”

For one thing, this family obviously adhered to Sumerian notions of the importance of business; otherwise it would hardly have occurred to the laconic narrator to mention “all their gain they had gained”—all the wealth they had accumulated during their stay in Harran. We know some of the ideas they brought with them—we can almost X-ray their mental baggage—for we can trace Sumerian religious notions in the earliest writings of the descendants of Avram. The voice that spoke to Avram was his patronal god; and in Avram’s mind he may not have been, to begin with, much different from Lugalbanda, Gilgamesh’s patronal god, whose statue Gilgamesh anointed for good luck. There were many

gods, but each human being had a guardian spirit—an ancestor or angel—charged with taking special care of him. These little gods, represented by amulets and portable statues, were, like all the gods, essentially familial—gods of the person, the family, the city, the tribe—and were jealous and contentious, like all family members. Even if in a particular situation they were not responsible for evil (though sometimes they were), in many situations they were powerless to counter evil—and, in any case, human beings were full of evil. “Man behaves badly,” pronounces Ut-napishtim sagely. “Never has a sinless child been born,” warns a favorite

Sumerian proverb. The way to success was to satisfy the duties of one’s cult, whatever those might be—which is why Sumerian temples were described with such precision and liturgies (including orgies and sacred couplings) enacted with such attention. It was by just such attention to cultic detail that Ut-napishtim had been found just; and such acts of piety were a Sumerian’s only insurance against the ill will of the gods.

We have already seen in the

Epic of Gilgamesh

some of the many mythological elements that would find their echo in the Bible. (The Gilgamesh story was so powerful that it would also influence the Greek stories that Homer would collect into the

Odyssey

as well as the

Arabian Nights

of medieval Islam.) As late as the sixth century

B.C.

, in the Jerusalem temple itself, Israelite women would sit and weep for the god Dumuzi (

Tammuz in the Bible), which the prophet Ezekiel notes with loathing. (The myth of the dying god casts so long a shadow that even today Tammuz is the name

for a month in the Jewish calendar.) The family of Terah no doubt took with them on their journey the stories of Sumer about the long-lived ancients and the ill-tempered gods—such as the story about the jealous goddess Ishtar, who had a sacred “tree of life,” guarded by a serpent, and the story about the ancestral figure whose unique piety enabled him to save a remnant of life in the great flood. And as the family of Terah looked back over their shoulders to the eastern horizon, the last thing they saw of Sumer was the

ziggurat of Harran, that bold Sumerian attempt to scale the heavens that would one day become the fabulous, foolish

Tower of Babel in Genesis.

But it is also true that, however “Sumerian” this expedition into the wilderness may have looked to the casual observer, its leader carried with him a brand-new idea.

We

know Avram was heading to Canaan, but did he? It is certain that the mention of Canaan in the summary account of the begettings and travels of Terah and his family is by way of overview and does not necessarily indicate that this destination was actually known to Avram when he started out. There is no reason to think that Avram knew where he was going or anything more than what his god had told him—that he was to “go forth” (the Hebrew imperative

“lekhlekha”

has an insistent immediacy that English cannot duplicate) on a journey of no return to “the land that I will” show you, that this god would

somehow

make of this childless man “a great nation,” and that all humanity would eventually find blessing through him.