The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (22 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

What had in fact been done was to authorise Germany to build to her utmost capacity for five or six years to come.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, in the military sphere the formal establishment of conscription in Germany on March 16, 1935, marked the fundamental challenge to Versailles. But the steps by which the German Army was now magnified and reorganised are not of technical interest only. The whole function of the Army in the National-Socialist State required definition. The purpose of the law of May 21, 1935, was to expand the technical élite of secretly trained specialists into the armed expression of the whole nation. The name Reichswehr was changed to that of Wehrmacht. The Army was to be subordinated to the supreme leadership of the Fuehrer. Every soldier took the oath, not as formerly to the Constitution, but to the person of Adolf Hitler, The War Ministry was directly subordinated to the orders of the Fuehrer. Military service was an essential civic duty, and it was the responsibility of the Army to educate and to unify, once and for all, the population of the Reich. The second clause of the law reads: “The Wehrmacht is the armed force and the school of military education of the German people.”

Here, indeed, was the formal and legal embodiment of Hitler’s words in

Mein Kampf:

The coming National-Socialist State should not fall into the error of the past and assign to the Army a task which it does not and should not have. The German Army is not to be a school for the maintenance of tribal peculiarities, but rather a school for the mutual understanding and adjustment of all Germans. Whatever may have a disruptive effect in national life should be given a unifying effect through the Army. It should furthermore raise the individual youth above the narrow horizon of his little countryside and place him in the German nation. He must learn to respect, not the boundaries of his birthplace, but the boundaries of his Fatherland; for it is these which he too must some day defend.

Upon these ideological bases the law also established a new territorial organisation. The Army was now organised in three commands, with headquarters at Berlin, Cassel, and Dresden, subdivided into ten (later twelve)

Wehrkreise

(military districts). Each

Wehrkreis

contained an army corps of three divisions. In addition a new kind of formation was planned – the armoured division, of which three were soon in being.

Detailed arrangements were also made regarding military service. The regimentation of German youth was the prime task of the new regime. Starting in the ranks of the Hitler Youth, the boyhood of Germany passed at the age of eighteen on a voluntary basis into the S.A. for two years. By a law of June 26, 1935, the work battalions or

Arbeitsdienst

became a compulsory duty on every male German reaching the age of twenty. For six months he would have to serve his country, constructing roads, building barracks, or draining marshes, thus fitting him physically and morally for the crowning duty of a German citizen – service with the armed forces. In the work battalions, the emphasis lay upon the abolition of class and the stressing of the social unity of the German people; in the Army, it was put upon discipline and the territorial unity of the nation.

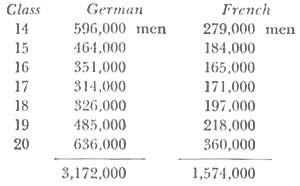

The gigantic task of training the new body and of expanding the cadres prescribed by the technical conception of Seeckt now began. On October 15, 1935, again in defiance of the clauses of Versailles, the German Staff College was reopened with formal ceremony by Hitler, accompanied by the chiefs of the armed services. Here was the apex of the pyramid whose base was now already constituted by the myriad formations of the work battalions. On November 7, 1935, the first class, born in 1914, was called up for service: 596,000 young men to be trained in the profession of arms. Thus, at one stroke, on paper at least, the German Army was raised to nearly seven hundred thousand effectives.

With the task of training came the problems of financing rearmament and expanding German industry to meet the needs of the new national Army. By secret decrees Doctor Schacht had been made virtual Economic Dictator of Germany. Seeckt’s pioneer work was now put to its supreme test. The two major difficulties were first the expansion of the officer corps, and secondly the organisation of the specialised units, the artillery, the engineers, and the signals. By October, 1935, ten army corps were forming. Two more followed a year later, and a thirteenth in October, 1937. The police formations were also incorporated in the armed forces.

It was realised that after the first call-up of the 1914 class, in Germany as in France, the succeeding years would bring a diminishing number of recruits, owing to the decline in births during the period of the World War. Therefore, in August, 1936, the period of active military service in Germany was raised to two years. The 1915 class numbered 464,000, and with the retention of the 1914 class for another year, the number of Germans under regular military training in 1936 was 1,511,000 men, excluding the para-military formations of the party and the work battalions. The effective strength of the French Army, apart from reserves, in the same year was 623,000 men, of whom only 407,000 were in France.

The following figures, which actuaries could foresee with some precision, tell their tale:

T

ABLE OF THE

C

OMPARATIVE

F

RENCH AND

G

ERMAN

F

IGURES

FOR THE

C

LASSES

B

ORN

FROM

1914

TO

1920,

AND

C

ALLED

UP FROM

1934

TO

1940

Until these figures became facts as the years unfolded, they were still but warning shadows. All that was done up to 1935 fell far short of the strength and power of the French Army and its vast reserves, apart from its numerous and vigorous allies. Even at this time a resolute decision upon the authority, which could easily have been obtained, of the League of Nations might have arrested the whole process. Germany either could have been brought to the bar at Geneva and invited to give a full explanation and allow inter-Allied missions of inquiry to examine the state of her armaments and military formations in breach of the Treaty; or, in the event of refusal, the Rhine bridgeheads could have been reoccupied until compliance with the Treaty had been secured, without there being any possibility of effective resistance or much likelihood of bloodshed. In this way the Second World War could have been prevented or at least delayed indefinitely. Many of the facts and their whole general tendency were well known to the French and British Staffs, and were to a lesser extent realised by the Governments. The French Government, which was in ceaseless flux in the fascinating game of party politics, and the British Government, which arrived at the same vices by the opposite process of general agreement to keep things quiet, were equally incapable of any drastic or clear-cut action, however justifiable both by treaty and by common prudence. The French Government had not accepted all the reductions of their own forces pressed upon them by their ally; but like their British colleagues they lacked the quality to resist in any effective manner what Seeckt in his day had called “The Resurrection of German Military Power.”

| 9 |

A Technical Interlude

, —

German Power to Blackmail — Approaches to Mr. Baldwin and the Prime Minister — The Earth versus the Air — Mr. Baldwin’s Invitation — The Air Defence Research Committee — Some General Principles — Progress of Our Work — The Development of Radar

—

Professor

Watson-Watt and Radio Echoes — The Tizard Report — The Chain of Coastal Stations — Air-Marshal Dowding’s Network of Telephonic Communications — The “Graf Zeppelin” Flies up Our East Coast: Spring of

1939

— I.F.F. — A Visit to Martlesham,

1939

— My Admiralty Contacts — The Fleet Air Arm — The Question of Building New Battleships — Calibre of Guns — Weight of Broadsides — Number of Turrets — My Letter to Sir Samuel Hoare of August

1, 1936

— The Admiralty Case — Quadruple Turrets — An Unfortunate Sequel — A Visit to Port Portland: the “Asdics.”

T

ECHNICAL DECISIONS

of high consequence affecting our future safety now require to be mentioned, and it will be convenient in this chapter to cover the whole four years which lay between us and the outbreak of war.

After the loss of air parity, we were liable to be blackmailed by Hitler. If we had taken steps betimes to create an air force half as strong again, or twice as strong, as any that Germany could produce in breach of the Treaty, we should have kept control of the future. But even air parity, which no one could say was aggressive, would have given us a solid measure of defensive confidence in these critical years, and a broad basis from which to conduct our diplomacy or expand our air force. But we had lost air parity. And such attempts as were made to recover it were vain. We had entered a period when the weapon which had played a considerable part in the previous war had become obsessive in men’s minds, and also a prime military factor. Ministers had to imagine the most frightful scenes of ruin and slaughter in London if we quarrelled with the German Dictator. Although these considerations were not special to Great Britain, they affected our policy, and by consequence all the world.

During the summer of 1934, Professor Lindemann wrote to

The Times

newspaper, pointing out the possibility of decisive scientific results being obtained in air defence research. In August, we tried to bring the subject to the attention, not merely of the officials at the Air Ministry who were already on the move, but of their masters in the Government. In September, we journeyed from Cannes to Aix-les-Bains and had an agreeable conversation with Mr. Baldwin, who appeared deeply interested. Our request was for an inquiry on a high level. When we came back to London, departmental difficulties arose, and the matter hung in suspense. Early in 1935, an Air Ministry Committee composed of scientists was set up and instructed to explore the future. We remembered that it was upon the advice of the Air Ministry that Mr. Baldwin had made the speech which produced so great an impression in 1933 when he said that there was really no defence. “The bomber will always get through.” We had, therefore, no confidence in any Air Ministry departmental committee, and thought the subject should be transferred from the Air Ministry to the Committee of Imperial Defence, where the heads of the Government, the most powerful politicians in the country, would be able to supervise and superintend its actions and also to make sure that the necessary funds were not denied. At this stage we were joined by Sir Austen Chamberlain, and we continued at intervals to address Ministers on the subject.

In February, we were received by Mr. MacDonald personally, and we laid our case before him. No difference of principle at all existed between us. The Prime Minister was most sympathetic when I pointed out the peace aspect of the argument. Nothing, I said, could lessen the terrors and anxieties which overclouded the world so much as the removal of the idea of surprise attacks upon the civil populations. Mr. MacDonald seemed at this time greatly troubled with his eyesight. He gazed blankly out of the windows onto Palace Yard, and assured us he was hardening his heart to overcome departmental resistance. The Air Ministry, for their part, resented the idea of any outside or superior body interfering in their special affairs, and for a while nothing happened.

I therefore raised the matter in the House on June 7, 1935:

The point [I said] is limited, and largely scientific in its character. It is concerned with the methods which can be invented or adopted or discovered to enable the earth to control the air, to enable defence from the ground to exercise control – indeed domination – upon airplanes high above its surface…. My experience is that in these matters, when the need is fully explained by military and political authorities, Science is always able to provide something. We were told that it was impossible to grapple with submarines, but methods were found which enabled us to strangle the submarines below the surface of the water, a problem not necessarily harder than that of clawing down marauding airplanes. Many things were adopted in the war which we were told were technically impossible, but patience, perseverance, and, above all, the spur of necessity under war conditions, made men’s brains act with greater vigour, and Science responded to the demands….