The Disorderly Knights (9 page)

Read The Disorderly Knights Online

Authors: Dorothy Dunnett

V:

Hospitallers

(Birgu, August 1551)

VI:

God Proposes

(Tripoli, August 1551)

VII:

But Allâh Disposes

(Tripoli, August 1551)

VIII:

Fried Chicken (The Yoke of the Lord)

(Tripoli, August 1551)

IX:

The Invalid Cross

(Tripoli, August 1551)

X:

Hospitality

(Malta, August 1551)

I

Sailing Orders

(

Mediterranean, June/July 1551

)

‘A

ND

this convenient Scotsman, where is he?’ asked the Constable of France, pacing the floor.

The Chevalier de Villegagnon, closing the window against the midsummer heat, turned back into the rich little room. ‘M. Crawford is coming. It is not yet the appointed time,’ he said.

‘We forget,’ said a voice from the shadows in Italian-French. ‘M. de Villegagnon is impressed by the gentleman.’

An older voice, in identical accent, answered drily. ‘If the young Queen of Scotland has survived her sojourn here in France, it is partly due at least to M. Crawford of Lymond, you must admit. Youth and bravado, Leone, are delicious assets.’

‘In the right place,’ said Leone Strozzi sardonically, and strolled away from his brother as voices outside told the Constable’s visitor had come.

Francis Crawford of Lymond, whose name, had he known it, was being bandied so freely at that time in Flaw Valleys and his own home, had then been in France for eight months; and his middling loyal activities during that time had brought him notoriety and a title, as well as the pressing interest of the Dowager Queen of Scotland, Mary of Guise, whose long visit to the court of France was nearly over.

When he appeared at the doorway of Constable Anne de Montmorency’s parlour at Châteaubriant, France, on that hot June morning of 1551, only Piero Strozzi and Nicholas Durand de Villegagnon, who had known him in his native land, could assess the changes which the high living so forcibly described by his brother had brought. To the rest he was a slender, wheaten-haired foreigner in virginal velvet, with an affable expression. He paused on the threshold for just long enough to scan the four other guests in the room—M. de Villegagnon, the brothers Piero and Leone Strozzi, and Francis of Lorraine, brother of the Queen Dowager of Scotland—before entering to deliver his bow to his host and be introduced.

The Constable of France, broad, grey and matted with age and

intrigue, smiled and lifted a great arm to the newcomer’s shoulder. ‘M. le Comte de Sevigny, is it not now?’ he said. ‘Let me introduce you to our friends. M. de Villegagnon you met in Scotland two years ago, he tells me, over a matter of a lady called—called …’

‘Hough Isa,’ said the Chevalier, smiling also, and gave Lymond his hand.

‘And M. Strozzi you met also—’

‘On the occasion of a wedding at Melrose. I remember, of course,’ said Lymond docilely, and got a sharp look from the Florentine black eyes.

‘But you have not yet encountered his brother Leone, General of the King’s Galleys in the Mediterranean. With M. de Villegagnon here, one of the great seamen of the world,’ said the Constable, throwing in some cursory tact.

‘I had the misfortune to be out of Scotland when Signor Leone paid us his memorable visit,’ said Lymond politely, and the second Strozzi brother, seal-like beside de Villegagnon’s ursine bulk, younger than the Chevalier by five years and than his brother by fifteen, bowed till the gold ring in his ear winked in the shafted sunlight and said, ‘I hear that you also, sir, have sailed in your time.’

With annoyance, the Constable saw that he was being left to retrieve this ill-timed reference to his guest’s informal past. Wishing, once more, that Leone Strozzi were not the Queen’s cousin, he said, ‘Some of the noblest captains on our seas have rowed for a year or two under the whip, Signor Strozzi.’

‘Such as Jean de la Valette,’ said de Villegagnon coldly, offering the name of one of Malta’s great captains.

‘Or Dragut,’ said Lymond cheerfully. ‘I met him once, I remember, off Nice. A most cordial encounter. We were in different boats but on the same side, of course … as the Grand Prior will appreciate,’ added the deprecating voice.

Francis of Lorraine, thus at last addressed, rose to his feet, scarlet to his soft hair line. At sixteen, the privilege of representing the Order of St John as Grand Prior of France was a prized and sensitive burden, as well as a lucrative one. Silent from youth and necessity, he returned the Scotsman’s bow until, straightening, he thought of something. ‘Whatever our allegiance to the King of France, Monsieur, our allegiance to God comes before it. I doubt if any member of my Order would call a murdering Turkish corsair

cordial

.’

‘But I,’ said Francis Crawford gently, ‘am not of your Order.’

And Piero Strozzi, a man of humour and of no ties with the Order of St John, concealed his amusement and sat in a mood of silent anticipation. For this artistic performer clearly understood every nuance of his invitation to dine with the Constable, and for the

Constable, unused to ambush in the bogs of statesmanship, the auspices were bad.

So, as every man there realized, with the possible exception of young Lorraine, was his dilemma. For the de Guise family, whose eldest sister Mary was Queen Dowager of Scotland, was becoming also too powerful in France. And with the coming marriage of the child Mary of Scotland to the Dauphin of France, the de Guises would be supreme behind the joint thrones of Scotland and France.

To curb the Queen Dowager’s power in Scotland were only a few strong Scottish families, dissatisfied with their French pensions, or with leanings towards the new religion and England. But these were hardly enough to keep her in check, so happily were they squabbling among themselves. And if Mary of Guise returned to Scotland with a new leader, a man of talent and panache, who would help her keep Scotland and maybe take Ireland too for the King of France, the power of her family would be beyond any control.

Similarly, if the King of France, so indebted to Crawford of Lymond for his services to the child Mary, chose with the de Guise family to make of Lymond an ally and a popular idol, the power of the Constable and the French Queen, silent in the daily company of her husband’s mistress, silent on the subject of the pregnant Lady Fleming, would silently drain away.

And meanwhile—‘As you have observed,’ said the Constable at last to Lymond as the marzipan was cleared away and the rosewater brought, ‘there are three Knights of Malta in this room. It is no coincidence. The Grand Prior and I have summoned M. de Villegagnon and M. Strozzi for the gravest of reasons.’

He paused. The Constable’s grand-uncle, as no one present ever forgot, had been first Grand Master of the Order of St John in Malta. It was one of the most useful relationships the Constable possessed, in an age where nepotism was not only legitimate but compulsory. Thoughtfully drying his hands on the towel proffered, ‘I cannot imagine why,’ said Lymond, and laid the silk down. ‘Unless the Sultan Suleiman is sending a corsair fleet against France?’

Piero Strozzi, commander and engineer, who had enjoyed every moment of his meal, caught the yellow-haired gentleman’s wide stare and grinned. ‘A little

too

disingenuous, sir,’ said the Florentine, and ignoring the Constable’s silence, continued comfortably.

‘Of course, France has been an ally of Turkey for years. We are not supporting the Moslem faith any more than Suleiman is supporting ours. But in face of the Emperor Charles V, dear small man who is enemy to us both, an alliance, military and naval, does exist. Added to that—’ Strozzi’s dark eyes strayed from the sardonic face of his brother to de Villegagnon’s steadfast stare, and from there to the

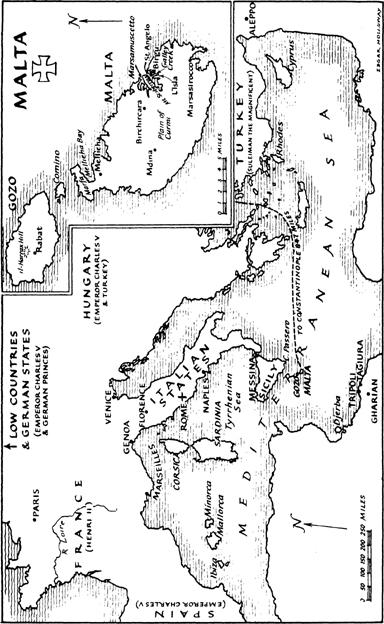

Grand Prior’s flushed face. ‘Added to that is the fact that Malta and Gozo were the Emperor Charles’s gifts to the Order, which would be homeless without them. The Knights of St John have lived rent-free on Malta for twenty-one years on condition that they defend it from the Turks, together with its neighbour Gozo, and Tripoli, over on the African coast. So that those gentlemen of France who have taken the holy vows of the Order have on occasion the unpleasant task of deciding whether to fight for the Order in the interests of the Emperor against the Turk … or whether to defend France from the Emperor, despite the fact that France’s allies are the very Moslems they are sworn to exterminate.… Am I right?’ said Piero Strozzi, smiling, to de Villegagnon.

The Chevalier did not return the smile. He said stiffly to Francis Crawford, ‘The Grand Prior has already made the position clear. To all Knights in the Order, whatever their nationality, allegiance to their Faith and the Order comes first.’

It was then that the knotted fist of Constable Anne de Montmorency fell; that the table rattled, chiming with abandoned silver, and the linen sprang grey with rosewater stains. Thick-built and grizzled; older than any man present, the Constable of France reared to his feet and stared at them all, jewelled and negligent round the small table in the leather-dressed room. ‘Is it a time for toying with words?’ he exclaimed. ‘For parlour phrases and pettishness? Have ye forgotten?’

‘

I

have not forgotten,’ said Francis of Lorraine passionately, jumping up. Striding to where Lymond was seated he put his two hands white-wristed on the table and bent, the pale hair under the velvet bonnet falling flat over his flushed brow. ‘If you are a man of no principle, leave us. If you are a man of no faith, abandon us. If you revere the infidel, go to him. But listen to this.

The Turkish fleet is at sea

. A hundred and twelve royal galleys, two galleasses, thirty flutes and more brigantines and troop ships under Sinan Pasha with Dragut, Salah Rais and twelve thousand men have left Constantinople and are sailing for Malta. The Chevalier de Villegagnon is leaving tonight for the island to warn the Grand Master. Signor Strozzi remains until there is a general call to arms, in case of attack by the Emperor on France. We wish to ask you, as a soldier and a man versed in ships, who has no national bias to affect his judgement and standing, to go with M. de Villegagnon and stir the Grand Master to Malta’s defence.’

‘

Against

,’ said Lymond drily, ‘Allâh’s Deputy on Earth?’

The boy straightened. ‘I have told you …’ he began.

‘Your allegiance is to God. I know,’ said Lymond. ‘But God knows the Sultan is going to be a little peevish when he notices that French knights are killing his Janissaries, whether in the Order or not. If I

were twenty Scotsmen you might hide your perfidious political faces behind me, but I cannot see that you may hide behind one.’

‘But you—’ began the Constable, a little tardily.

‘—are the equal of twenty. I believe it. But would your Treasurer believe it?’ said Francis Crawford amiably.

There was a crisp silence. However couched, the demand was extortionate. It was contemptible. De Villegagnon frowned; Leone Strozzi smiled; and the Constable’s face reddened with feeling even while he slowly agreed, as agree he must. Only Piero Strozzi looked thoughtfully at the speaker, knowing that Francis Crawford was wealthy enough to need no bribing, and sophisticated enough to find this kind of exercise mortally dull.

What he did not know was that the same Francis Crawford had found out only that morning that an Irishwoman called Oonagh O’Dwyer had just taken ship at Marseilles for the island of Gozo. And that if Francis Crawford reached Malta, it was because he always meant to reach Malta; not to fight, but to recruit.

In any case, it made no odds to the Order. The Order had got what it wanted; would have got what it wanted even had Lymond spurned them all and returned home to Scotland … since it was for no disingenuous reason that M. de Villegagnon, Chevalier of St John, had placed on Lord Culter’s anxious shoulders the responsibility for Gabriel’s sister of the apricot hair.

*

With de Villegagnon and his suite, Lymond left that night for Marseilles. Before he went he did some brief leave-taking: of the King, of his friends and followers at court, of the Queen Dowager and Margaret Erskine, Tom’s bride.

These last he got over quickly. Margaret, sober daughter of Jenny Fleming and herself a good friend in need, was pleased, he thought, even without understanding his motives. The Queen Dowager was angry.

‘And what do I tell my child?’ asked Mary of Guise. ‘That you are now compelled to seek excitement and fortune among her enemies?’

‘I do not expect,’ said Lymond, ‘to be fighting quite under the banner of the Emperor Charles. And if I were, I could hope surely for nothing better than to stand shoulder to shoulder with the Grand Prior of France.’