The Coming Plague (68 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

Two key features of those monkey populations that thrived despite the habitat shrinkage were their ability to adapt to

Homo sapiens'

pressure and their cross-species group behavior. For example, the tough African green monkey species was adept at scavenging human eating and food storage areas and would boldly raid houses.

Homo sapiens'

pressure and their cross-species group behavior. For example, the tough African green monkey species was adept at scavenging human eating and food storage areas and would boldly raid houses.

In the wild, many monkey, and occasionally chimpanzee, species lived and traveled in mixed troops. This worked well when the various species within the mixed troops had different, noncompetitive diets. And the advantage

was clear: a larger pack allowed for greater protection from predators and more effective use of a limited ecology.

211

was clear: a larger pack allowed for greater protection from predators and more effective use of a limited ecology.

211

From the microbial point of view, shrinking primate habitats and mixedtroop behavior opened the possibility for cross-species transmission among three or more monkey/chimp species. In such an environment various SIV strains had ample opportunity to move from immune hosts to vulnerable simian species. And an immune species that thrived alongside

Homo sapiens,

such as vervet African green monkeys, might conceivably serve as an SIV/HIV conduit, carrying viruses back and forth between mixed monkey troops and humans.

Homo sapiens,

such as vervet African green monkeys, might conceivably serve as an SIV/HIV conduit, carrying viruses back and forth between mixed monkey troops and humans.

It was speculation, of course. No one could be certain how the immunodeficiency viruses zoonotically moved among primates in ancient Africa.

Lentivirus expert Dr. Matthew Gonda, of the National Cancer Institute, argued that biology played no substantial role in the sudden explosion of HIV, which, he said, “has been around for thousands of years.” Rather, “the key lies with the demographics of Africa.”

In that vein, Dr. Anthony Pinching, of St. Mary's Hospital Medical School in London, maintained that “HIV could have been present, and even causing disease, in a human population in a remote rural region for some time, yet remain undetected. It could then have been transmitted to others following the movements of peoples, especially to the urban areas of Africa. Its subsequent spread would reflect the existing modes of sexual contact in these urban areas ⦠. The new seed was thus propagated on the existing soil of human behavior.

“If African countries had had the resources available in the USA during the mid-1970s, we would have seen AIDS emerging [then] as a sexually transmitted disease,” Pinching said.

212

212

Abraham Karpas, of Cambridge University, felt that human behavior was the key, but put primary blame on widespread use of nonsterile syringes in Africa, which “arrived together with antibiotics. As the early generation of antibiotics came only as injectable medicines, the needle and syringe became inseparable from their therapeutic effect. Even now, injectable medication is the treatment of choice in Africa and in other countries.”

213

213

Â

In retrospect, social conditions in 1975â80 were clearly ripe for the emergence and spread of even an extremely rare virus. Witness the case of HTLV-I and HTLV-II. Discovered at about the same time the AIDS epidemic was first noted, both were considered extremely rare human microbes, found almost exclusively in remote pockets of the

Homo sapiens

population. In 1980 studies showed fewer than 1 percent of the general populations of Europe, Japan, and North America were infected with HTLV-I. But people with hemophilia were rapidly getting infected in the United States: by 1981, one out of nine Georgians with hemophilia carried HTLV-I, as did one out of six New Yorkers with hemophilia.

214

HTLV-I would

prove endemic to pockets of Japan, the Caribbean basin, Melanesia, and Africa, and immigrants from those areas would carry the viruses to new regions. By 1993 the New York City borough of Brooklyn would have an HTLV-I infection rate of 5 percent of the adult populationâup from about 0.01 percent a decade earlier.

215

Homo sapiens

population. In 1980 studies showed fewer than 1 percent of the general populations of Europe, Japan, and North America were infected with HTLV-I. But people with hemophilia were rapidly getting infected in the United States: by 1981, one out of nine Georgians with hemophilia carried HTLV-I, as did one out of six New Yorkers with hemophilia.

214

HTLV-I would

prove endemic to pockets of Japan, the Caribbean basin, Melanesia, and Africa, and immigrants from those areas would carry the viruses to new regions. By 1993 the New York City borough of Brooklyn would have an HTLV-I infection rate of 5 percent of the adult populationâup from about 0.01 percent a decade earlier.

215

Like HIV, HTLV-I would be linked to homosexual transmission. In Trinidad, for example, gay men would prove seven times more likely to carry the virus than straight men, and up to 15 percent of gay Trinidadians would test positive for HTLV-I in 1986.

216

216

Similarly, HTLV-II would initially be found among Native Americans (in the United States, Panama, Colombia) and be considered an extremely rare event outside those populations. But in 1989 Irvin Chen's UCLA group discovered HTLV-II virus in 21 of 121 injecting drug users in New Orleans, Louisiana.

217

Studies of injecting drug users in Miami and Newark, New Jersey, revealed similar rates of HTLV-II infection, and showed that strains found in the three cities varied genetically by less than 6 percent, implying that their emergence in drug users spanning such distances was an extremely recent event.

218

217

Studies of injecting drug users in Miami and Newark, New Jersey, revealed similar rates of HTLV-II infection, and showed that strains found in the three cities varied genetically by less than 6 percent, implying that their emergence in drug users spanning such distances was an extremely recent event.

218

The origin and spread of the HTLVs, which was not particularly controversial, could have served as a useful illustration of the principles at work with HIV. The HTLVs were ancientâprobably older than HIVâyet they seemed to have spread radically outside isolated human pockets only in the late 1970s or early 1980s. Historical blood sample analysis demonstrated that this rapid spread was not an artifact of discovery. The factors for the viruses' emergence from isolated human groups to larger populations were apparent: injecting drug use and needle sharing, multiple partner sex (both gay and heterosexual), blood products, and transfusions.

It is probably impossible to pinpoint which factor(s) played the greatest role in HIV-1's emergence from an apparently obscure virus that, for example, infected less than 1 percent of the rural Yambuku and N'zara populations in 1976, and perhaps 0.1 percent of isolated populations of Europe or North America during the same period, twenty-four months later exploding into a global pandemic that threatened to kill as many as twenty million adults and over one million children by the year 2000. But Joe McCormick's reminder to “look at human beings” was helpful.

“Human beings have done it to themselves,” McCormick said. “And that's not moralistic, it's just a fact.”

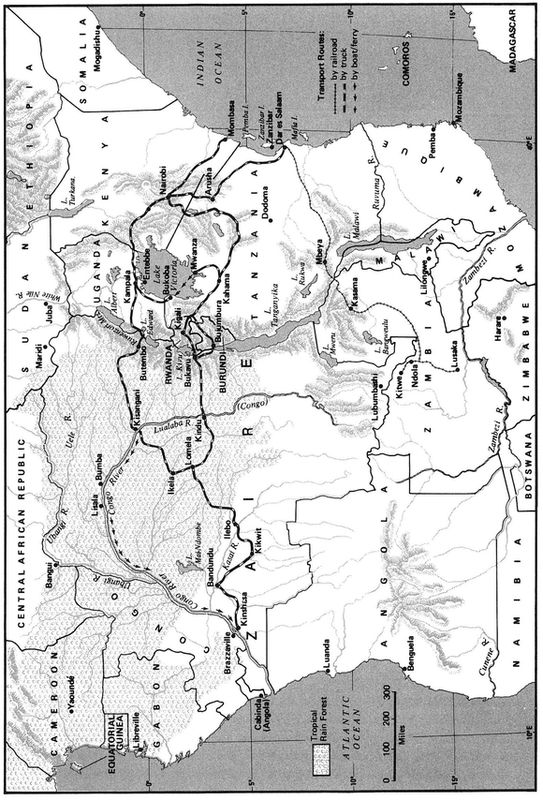

In Africa, many factors undoubtedly played a role in amplifying the otherwise rare incidence of HIV. The epidemiologic record argues for amplified emergence somewhere around the eastern Lake Victoria/northwestern Zaire region. Crucial data that could help solve that area's AIDS puzzle was never collected, undoubtedly for political and logistic reasons: missing from the equation are representative blood samples from veterans of the Tanzanian/Ugandan war, female victims of rape during that war, and

the first wave of female prostitutes that left the war-torn area in search of livings in nearby urban centers.

the first wave of female prostitutes that left the war-torn area in search of livings in nearby urban centers.

Nevertheless, it is tempting to conclude, as many of the physicians of the Bukoba and Rakai districts have, that the war played a pivotal role in the emergence of HIV-1 in Central Africa.

219

219

Primary truck routes for shipment of goods between the eastern port cities of Dar es Salaam and Mombasa to landlocked Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, and eastern Zaire all passed through the former war zone. And by 1990 the link between those truck routes and the spread of HIV, via brothels and

femmes libres

along the roadsides, would be thoroughly documented. Finally, the extraordinary incidence of HIV-1 infection in the area, as well as the presence of the particularly lethal D clade of the virus, argued for an especially volatile epidemic.

femmes libres

along the roadsides, would be thoroughly documented. Finally, the extraordinary incidence of HIV-1 infection in the area, as well as the presence of the particularly lethal D clade of the virus, argued for an especially volatile epidemic.

The postwar dispersal patterns of prostitutes and truckers from the region mirrored the second wave of Central Africa's HIV-1 epidemic.

HIV-1's emergence in North America was almost certainly driven by the overlapping injecting-drug-using/gay male population, but here again the crucial data were missing. It was not possible to work backward in time to the pre-1975 period in New York, San Francisco, Miami, Newark, and Los Angeles to determine which group first had a significant level of HIV-1 infection.

Of note, however, was the fact that gay men of the 1970s were very actively interacting with the U.S. and European medical systems due to their high rates of STDs and comparatively good incomes, which allowed them full access to health care. Several national and local health surveys were underway in the U.S. gay population in the 1970s. And many of America's prominent physicians and nurses were themselves gay. Yet the HIV epidemic wasn't detected in that population until 1981.

In contrast, the injecting-drug-using population was generally outside the medical system, even in countries that had nationalized health care. Drug users interacted primarily with emergency rooms and so-called street clinics. As noted earlier, the medical profession found drug users a difficult, even distasteful, population and few doctors were closely following health trends in that group during the 1970s. Arguably, it would have been easy for isolated early cases of AIDS to go undetected in drug users.

There was a crying need for what Gerald Myers called “fossil viruses,” particularly from Western Europe and North America, to help solve the mystery of the 1959 Manchester sailor. Was he, as Myers asserted, an aberration? Or were there European pockets of low-level HIV endemicity in ports of call along his 1950s voyages?

If HIV originated in Africa during the 1970s, scientists must explain why only the Type B clade of the virus had taken hold, after fifteen epidemic years, in Europe and North America. And why HIV-2 had yet to take hold on either continent.

Â

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Another piece of missing data concerned the remarkable coincidence of HIV-2 and areas of former Portuguese colonization (Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, São Tome and Principe). The only East African site of HIV-2 was in Mozambique, and West African ex-colonies had among the highest incidences of HIV-2. It would have been helpful if somebody had systematically tested Portuguese and African veterans of the 1965â75 colonial wars to determine whether these soldiers caught, and spread, the virus.

For an obscure blood-borne virus to find its way into large segments of the world's population a crucial amplification step must have taken place. Something new and radical must have occurred that fundamentally altered an ancient homeostatic relationship between humans and the microbe. Ideally, such an amplifier would have provided the microbial population with several key opportunities to spread rapidly outside of its ancient niche.

Between 1970 and 1975 the world offered HIV an awesome list of amplification opportunities: multiple partner sexual activity increased dramatically among gay North American and European men and among African urban heterosexuals; needles were introduced to the African continent on a massive scale for medical purposes, and then resupplied so poorly that their constant reuse on hundreds, even thousands, of people was necessary; heroin use, coupled with amphetamines and cocaine, soared in the industrialized world; waves of other sexually transmitted diseases swept across the same regions, lowering affected individuals' resistance to disease and creating genital and anal portals of entry for the virus; the global blood market exploded into a multibillion-dollar industry; primate research expanded; and governments all over the world turned their backs, convinced, as they were, that the age of plagues and pestilence had passed.

Though it had been the focus of attention of some of the greatest minds in contemporary biomedical science on at least four continents, nobody by 1994 had yet pinpointed a time, place, or key event responsible for the emergence of HIV-1.

But the human factors responsible for amplification of that event, for the rapid expansion of an isolated infection to an outbreak cluster and later epidemic, were very well understood. The World Health Organization was able to delineate those factors repeatedly in pamphlets, and the UN General Assembly would adopt resolutions that cited factors for societal emergence of HIV.

Yet the virus would continually find vulnerable

Homo sapiens

all over the world, for the human factors responsible for spread of the virus would resist change. Governments of countries without AIDS would smugly deny the correlation of such behaviors with the inevitable arrival of the virus. And in nation after nation, when AIDS arrived it would find conditions ideal for rapid spread, and politicians would be unwilling to take unpopular steps to acknowledge the threat, thereby possibly altering the epidemic's course.

Homo sapiens

all over the world, for the human factors responsible for spread of the virus would resist change. Governments of countries without AIDS would smugly deny the correlation of such behaviors with the inevitable arrival of the virus. And in nation after nation, when AIDS arrived it would find conditions ideal for rapid spread, and politicians would be unwilling to take unpopular steps to acknowledge the threat, thereby possibly altering the epidemic's course.

Understanding how humanity aids and abets emerging microbes would soon be Jonathan Mann's most important lesson, learned, ironically, in one of the planet's coziest, safest, most sanitized locales.

Other books

The Rossetti Letter (v5) by Phillips, Christi

The Boarded-Up House by C. Clyde Squires

In Plain View (Amish Safe House, Book 2) by Ruth Hartzler

Cotton’s Inferno by Phil Dunlap

The Scum of All Fears: Squeaky Clean Mysteries, Book 5 by Barritt, Christy

Lost... In the Jungle of Doom by Tracey Turner

Hemispheres by Stephen Baker

Where The Heart Is (Choices of the Heart, book 1) by Jennie Marsland

With the Might of Angels by Andrea Davis Pinkney

Open by Ashley Fox