The Coming Plague (43 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

Bates insisted: “The goal of prevention was frequently compromised. Physicians often discharged still infectious patients, and men and women with communicable disease left institutions against advice. Instead of a system that cured and prevented disease, society had built one that met some needs of sick and dependent people, spared families some of the burdens of care at home, and reduced the public's fear of infection, if not the actual threat. These unanticipated results grew out of political, social, and economic transactions in which medical understanding of tuberculosis played only a subordinate part.”

27

27

Another way to answer the question of what factors had been key to Europe's TB decline was to study the disease in an area that was making a transition during the twentieth century that was roughly equivalent to Northern Europe's Industrial Revolution a century earlier. South Africa fit the bill, and was a good place to test the hypotheses of McKeown, Dubos, and others: the country's European descendants had a standard of living and disease patterns analogous to their counterparts in the Northern Hemisphere. But the African and Indian residents suffered from marked economic and social deprivation. Their communities bore a striking resemblance to the squalid living conditions endured by London's working classes in the 1850s.

Though antibiotics and curative medicine existed, coupled with scientific knowledge of the modes of transmission of the bacteria, tuberculosis death rates rose 88 percent in South Africa between 1938 and 1945. Cape Town's rate increased 100 percent; Durban's 172 percent; and Johannesburg's 140 percent. In the rural areas, despite poverty and hunger, active TB cases and deaths never exceeded 1.4 percent in any surveyed group. But in the cities, incidence rates as high as 7 percent were commonplace by 1947. Nearly all TB struck the country's black and so-called colored populations.

The key to the increase in TB seemed not to rest with the health care system, for little had changed during those years. Nor were the diets of black South Africans much alteredâthey had been insufficient for decades.

The answer, it seemed, was housing. From 1935 to 1955, South Africa underwent its own Industrial Revolution, having previously been a largely agrarian society. As had been the case a century earlier in Europe, this required recruitment of a cheap labor force into the largest cities. But South Africa had an additional factor in its socioeconomic paradigm: racial discrimination.

The recruited labor was of either the black or the colored race, prescribed by law to live in designated areas and carry identity cards which stipulated their sphere of mobility. The government subsidized an ambitious program of urban housing development for white residents of the burgeoning cities, but government-financed housing construction for black urbanites during the period of metropolitan expansion actually declined by 471 percent.

28

The recruited labor was of either the black or the colored race, prescribed by law to live in designated areas and carry identity cards which stipulated their sphere of mobility. The government subsidized an ambitious program of urban housing development for white residents of the burgeoning cities, but government-financed housing construction for black urbanites during the period of metropolitan expansion actually declined by 471 percent.

28

By the 1970s, South Africa was generating 50,000 new tuberculosis cases a year, and the apartheid-controlled public health agencies were arguing that blacks had some unidentified genetic susceptibility to the disease. In 1977 the government made many of its worst TB statistics disappear by setting new boundaries of residence for blacks. The TB problem “went away” when hundreds of thousands of black residents of the by then overly large cities were forcibly relocated to so-called homelands, or when their urban squatter communities were declared outside the city's jurisdiction and, therefore, its net of health surveillance.

29

29

If the South African paradigm could be applied broadly, then, it lent some support to Dubos's theories, underscoring human squalor as the key ecological factor favoring

M. tuberculin

transmission, but it failed to support Dubos's other assertions about the role of working conditions.

M. tuberculin

transmission, but it failed to support Dubos's other assertions about the role of working conditions.

One thing that cities of the wealthy industrialized world and the far poorer developing world had in common was an ecology ideal for the emergence of sexually transmitted diseases, particularly syphilis. Certainly people had sex regardless of where they lived, but cities created options. The sheer density of

Homo sapiens

populations, coupled with the anonymity of urban life, guaranteed greater sexual activity and experimentation. Since ancient times urban centers had been hubs of profligacy in the eyes of those living in small towns and villages.

Homo sapiens

populations, coupled with the anonymity of urban life, guaranteed greater sexual activity and experimentation. Since ancient times urban centers had been hubs of profligacy in the eyes of those living in small towns and villages.

Houses of both male and female prostitution, activities mainstream societies often labeled “deviant” such as homosexuality, orgies, even religiously sanctioned sexual activity, were common in the ancient cities of Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, and the Hindu empires and among the Aztecs and the Mayans. The double standard of chastity in the home and risque behavior in the anonymity of the urban night dates back as far as the beginning of written history.

It seemed surprising, then, that syphilis did not reach epidemic proportions until 1495, when the disease broke out among soldiers fighting on behalf of France's Charles VIII, then waging war in Naples. Within two years, however, it was known the world over. Syphilis seemed to have hit

Homo sapiens

as something completely new, because in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it struck in a far more fulminant and deadly form than it would take by the dawn of the twentieth century.

Homo sapiens

as something completely new, because in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it struck in a far more fulminant and deadly form than it would take by the dawn of the twentieth century.

Syphilis was caused by a spirocheteâor spiral-likeâbacterium called

Treponema pallidum

, the same organism that caused the childhood skin disease known as yaws. Evidence of the existence of yaws clearly dated

back to ancient times, yet of syphilis there was no hint prior to the fifteenth century.

Treponema pallidum

, the same organism that caused the childhood skin disease known as yaws. Evidence of the existence of yaws clearly dated

back to ancient times, yet of syphilis there was no hint prior to the fifteenth century.

Several twentieth-century theories were offered to explain this puzzle. The most obvious solution was to blame Amerindians, Christopher Columbus, and his crew. Their 1492 voyage to the Americas and subsequent return to Spain coincided with the 1495 emergence of the disease during the Franco-Italian wars. So it seemed circumstantially convenient to conclude that syphilis originated among the Native American peoples, was picked up by Spanish sailors, and carried back to Spain.

There were, however, two problems with that suggestion. First of all, yaws was an ancient disease on both continents, passed by skin contact between people. If yaws had existed on every continent, certainly the potential for syphilis had also always been present worldwide.

Second, syphilis wiped out Amerindians in the fifteenth century with a ferocity equal to the force of its attack on North Africans, Asians, and Europeans. If it had been endemic in the Americas, the Amerindians should have developed at least partial immunity to it.

The most likely explanation for the apparently sudden emergence of syphilis came in the late 1960s from anthropologist-physician Edward Hudson, who argued that syphilis was a disease of “advanced urbanization,” whereas yaws was “a disease of villages and the unsophisticated.”

30

In Hudson's view the spirochete could best exploit the ecology of the village by taking advantage of the frequent cuts and sores on the legs of children, coupled with the close leg-to-leg contact of young people who slept together in rural hovels and huts.

30

In Hudson's view the spirochete could best exploit the ecology of the village by taking advantage of the frequent cuts and sores on the legs of children, coupled with the close leg-to-leg contact of young people who slept together in rural hovels and huts.

When the spirochete settled under the skin it produced only a localized infection that eventually healed. Transmission could occur only during the few weeks when the sore was raw and skin-to-skin contact could allow the organism to jump from one person to another. This occurred most easily among children who played or bedded down together.

Sexual transmission of the spirochete, however, required a far more complex human ecology in which many hundreds or thousands of people interacted intimately every day and a large percentage of the population regularly had sexual intercourse with a variety of partners.

Other twentieth-century theorists went further, arguing that the sexually transmitted microbes could

only

emerge in a population of

Homo sapiens

or animals in which a critical massâperhaps even a definable numberâof adults in the population had frequent intercourse with more than one partner. Clearly, they argued, a strict society in which every adult had sex only with their lifetime mate would have an extremely low probability of providing the

Treponema

spirochete with the opportunity to switch from a skin contact yaws producer to sexual syphilis.

only

emerge in a population of

Homo sapiens

or animals in which a critical massâperhaps even a definable numberâof adults in the population had frequent intercourse with more than one partner. Clearly, they argued, a strict society in which every adult had sex only with their lifetime mate would have an extremely low probability of providing the

Treponema

spirochete with the opportunity to switch from a skin contact yaws producer to sexual syphilis.

Conversely, in cities where social taboos were less enforceable or respected, the possibility of multiple-partnering and, therefore, sexual passage of disease was far greater.

Following the Black Death of the fourteenth century, most of Europe experienced two or three generations of disarray and lawlessness. Death had taken a toll on the cities' power structures and, in many areas, the worst of the survivorsâthe most avaricious and corruptâswept in to fill the vacuums.

“The crime rate soared; blasphemy and sacrilege was a commonplace; the rules of sexual morality were flouted; the pursuit of money became the be-all and end-all of people's lives,” Philip Ziegler wrote.

31

The world was suddenly full of widows, widowers, and adolescent orphans; none felt bound by the strictures of the recent past. Godliness had failed their dead friends and relatives; indeed, the highest percentage of deaths had occurred among priests. Europe, by all accounts, remained so disrupted for decades.

31

The world was suddenly full of widows, widowers, and adolescent orphans; none felt bound by the strictures of the recent past. Godliness had failed their dead friends and relatives; indeed, the highest percentage of deaths had occurred among priests. Europe, by all accounts, remained so disrupted for decades.

One could hypothesize the following scenario for the emergence of syphilis: the spirochete was endemic worldwide since ancient times, usually producing yaws in children. But on rare occasionsâagain, since prehistoryâit was passed sexually, causing syphilis.

32

These events were so unusual that they never received a correct diagnosis and may well have been mistaken for other crippling ailments, such as leprosy. But amid the chaos and comparative wantonness that followed the Black Death, that necessary critical mass of multiple-partner sex was reached in European cities, allowing the organism to emerge within two or three human generations on a massive scale in the form of syphilis.

32

These events were so unusual that they never received a correct diagnosis and may well have been mistaken for other crippling ailments, such as leprosy. But amid the chaos and comparative wantonness that followed the Black Death, that necessary critical mass of multiple-partner sex was reached in European cities, allowing the organism to emerge within two or three human generations on a massive scale in the form of syphilis.

In the late twentieth century similar debates about the emergence of other sexually transmitted diseases would take placeâdebates that might have been easier to resolve if questions regarding the sudden fifteenth-century appearance of syphilis had been settled.

By 1980 there were five billion people on the planet, up from a mere 1.7 billion in 1925.

The cities became hubs for jobs, dreams, money, and glamour, as well as magnets for microbes.

Once entirely agrarian,

Homo sapiens

was becoming an overwhelmingly urbanized species. Overall, the most urbanized cultures of the world were also, by 1980, the richest; and with the notable exception of China, the richest individual citizens usually resided in the largest cities or their immediate suburbs.

Homo sapiens

was becoming an overwhelmingly urbanized species. Overall, the most urbanized cultures of the world were also, by 1980, the richest; and with the notable exception of China, the richest individual citizens usually resided in the largest cities or their immediate suburbs.

Propelled by obvious economic pressures, the global urbanization was irrepressible and breathtakingly rapid.

By 1980 less than 10 percent of France's population was rural; on the eve of World War II it had been 35 percent. The number of French farms plummeted between 1970 and 1985 from nearly 2 million to under 900,000.

33

33

In Asia only 270 million people were urbanites in 1955. By 1985 there were 750 million, and that figure was expected to top 1.3 billion by 2000.

34

34

Worldwide, the percentage of human beings living in cities showed a steady climb, and from less than 15 percent in 1900, was expected to exceed 50 percent by 2010.

35

About 60 percent of this extraordinary urban growth was due to babies born in the cities; 40 percent of the new urbanites were young adult rural migrants or immigrants moving from poor countries to the large cities of wealthier nations.

36

35

About 60 percent of this extraordinary urban growth was due to babies born in the cities; 40 percent of the new urbanites were young adult rural migrants or immigrants moving from poor countries to the large cities of wealthier nations.

36

The most dramatic rural/urban shifts were occurring in Africa and South Asia, where tidal waves of people poured continuously into the cities throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. Some cities in these regions doubled in size in a single decade.

37

37

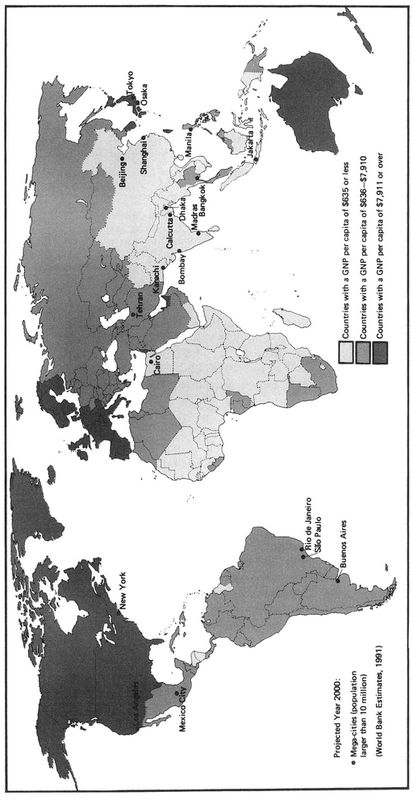

The bulk of this massive human population surge occurred in a handful of so-called megacitiesâurban centers inhabited by more than 10 million people. In 1950 there were two megacities: New York and London. Both had attained their awesome size in less than five decades, growing by just under 2 million people each decade. Though the growth was difficult and posed endless problems for city planners, the nations were wealthy, able to finance the necessary expansion of such services as housing, sewage, drinking water, and transport.

By 1980, however, the world had ten megacities: Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Mexico City, Los Angeles, New York, Beijing, Shanghai, Tokyo, and London. And even wealthy Tokyo found it difficult to accommodate the needs of its new population, which grew from a mere 6.7 million in 1950 to 20 million in 1980.

But this was only the beginning. Continued urban growth was forecast, and it was predicted that by 2000 there would be 3.1 billion

Homo sapiens

living in increasingly crowded cities, with the majority crammed into 24 megacities, most of them located in the world's poorest countries.

38

Homo sapiens

living in increasingly crowded cities, with the majority crammed into 24 megacities, most of them located in the world's poorest countries.

38

Throughout the 1980s a key shift would occur, and most of the nations experiencing the greatest population growth would also rank among the poorest countries in the world. They would be hard pressed to meet the health and service challenges posed by the cities' extraordinary escalation in need.

The World Health Organization concluded that “urban growth, instead of being a sign of economic progress, as in the industrialized country model, may thus become an obstacle to economic progress: the resources needed to meet the increasing demand for facilities and public services are lost to potential productive investment elsewhere in the economy.”

39

39

According to the World Bank, African cities were increasing in size by 10 percent a year throughout the 1970s and 1980s, which constituted the most rapid proportional urbanization in world history.

In 1970, in the Americas there were three city residents for every rural resident; by 2010 the ratio would be four to one. The same shift was forecast for Europe, both Western and Eastern. Some Asian countries were predicted to have five urban residents for every one rural individual by 2010.

Â

GLOBAL PER CAPITA EARNIGS

During the 1970s and 1980s this crush of urban humanity was causing severe growth pains that directly impacted on human health, even in the wealthier nations. Japan, which was quickly becoming one of the two or three wealthiest countries on the planet, was reeling under Tokyo's expanding needs. By 1985 less than 40 percent of the city's housing would be connected to proper sewage systems, and tons of untreated human waste would end up in the ocean.

40

40

Hong Kong, a center of wealth for the Chinese-speaking world, was dumping one million tons of unprocessed human waste into the South China Sea daily. Nearby Taiwan had sewage service for only 200,000 of its 20 million people, two-thirds of whom lived in its four largest cities.

But for the poorest developing countries, the burden of making their growing urban ecologies safe for humans, rather than heavens for microbes, proved impossible. Except for a handful of East Asian states which developed strong industrial capacities (i.e., South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore), the developing world simply had no cash in 1980.

In addition to growing national debts, developing countries faced the steady capital drain of paying off development loans obtained during the 1960s and 1970s and investing in newer sources of potential revenue generation. Some countries simply couldn't bear the burden, and shirked or attempted to renegotiate their multibillion-dollar loans.

The capital drain would turn into a hemorrhage. In 1980 the Latin American nations collectively were receiving from their external creditorsâmajor banks, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bankâabout $11 billion more than they were losing in capital transfers back to wealthy-nation interests. But by 1985 these nations would be losing $35 billion more a year in capital transfers to North America and Europe than they received in loans and investments.

41

41

Africa was also staggering under the burden of debt servicing and capital transfer, though the impact wasn't as profound in dollar terms as that seen in Latin America. In 1979 the recently elected Prime Minister of the U.K., Margaret Thatcher, addressed these concerns in frank terms in a speech before the Commonwealth Conference, convened that year in Lusaka, Zambia. Ministers from the poorest of England's former colonies hoped that Thatcher would extend a pound-filled hand, but she proffered only the sorry news that the once-great Empire was itself feeling the economic pinch. In short, it was time for a global belt tightening.

The cities worsened, some coming to resemble their teeming counterparts in nineteenth-century Europe. By the mid-1980s, 100 million newly homeless adults would roam the streets of developing-world cities; at least 100 million abandoned street children would haunt the urban nights. Half the city dwellers of developing countries who were not classified as homeless would live in shantytowns and slums that, among other things, lacked safe

drinking water. Forty percent would be without public sanitation or sewage facilities. A third would live in areas in which there were no garbage or solid waste collection services.

drinking water. Forty percent would be without public sanitation or sewage facilities. A third would live in areas in which there were no garbage or solid waste collection services.

As was the case in ancient Rome, it was healthier to remain in the villages and small towns of the developing worldâeven in times of drought and crop failureâthan to live in the filthy, unwieldy metropolises. The average child living in a typical developing-country urban slum was forty times more likely to die before his or her fifth birthday of a preventable infectious disease than was a typical rural child in the same country.

42

42

Disasters, and the very real opportunities they afforded the microbes, were everywhere. The streets of Cairo, for example, were flooded in December 1982 with sewage water that in some places was knee-deep. The flooding persisted for day after day, while authorities struggled to identify its cause.

43

43

Nearly every Egyptian had been, for over 4,000 years, dependent on a single water supplyâthe Nile. The river's annual floods would carry away a host of human sins in the form of waste and soil overuse, and leave behind a thick layer of fresh, fertile silt.

But construction of the Aswan Dam, coupled with Egypt's extraordinary human population explosion, had erased the Nile's majesty. Now slow-moving and predictable, the Nile was filling up with silt, fertilizers (which the farmers now needed because they no longer got the topsoil from the annual Nile floods), sewageâboth treated and untreatedâand industrial waste. Scientists predicted the imminent demise of Alexandria's freshwater delta lagoons, a rise in the level of the Mediterranean Sea, and serious public health risks due to chemical and biological pollution of the Nile. They suggested that, given Cairo's growth rate, there was nothing that could be done to prevent future environmental and public health disasters.

44

44

The World Bank rated 79 percent of the housing of Addis Ababa “unfit for human habitation” in 1978. A quarter of the city's houses were without toilet facilities.

A quarter of Bangkok's residents in 1980 had no access to health care, according to the World Bank. In the Dharavi slum of Bombay, then inhabited by over 500,000 people, conditions were so appalling that 75 percent of the women suffered chronic anemia, 60 percent of the population was malnourished, pediatric pneumonia afflicted nearly all children, and most residents contracted gastrointestinal disorders due to parasitic infections. In Jakarta in 1980, the life expectancy was only fifty years, several years less than in the countryside. By 1980, 88 percent of Manila's population lived in squatter settlements constructed of discarded pieces of wood, cardboard, tin, or bamboo. Forty percent of Nairobi's 827,000 people in 1979 lived in housing so poor that their neighborhoods were deliberately omitted from all official maps.

45

The flood of people into the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, led to epidemics of malaria, diarrheal diseases, anemia (presumably produced by malaria), measles, whooping cough, and diphtheria

in the early 1980s. In the Ivory Coast, rural tuberculosis rates by 1980 were down to 0.5 percentâa success story. But in the large capital city of Abidjan the TB rate was 3 percent and climbing.

46

45

The flood of people into the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, led to epidemics of malaria, diarrheal diseases, anemia (presumably produced by malaria), measles, whooping cough, and diphtheria

in the early 1980s. In the Ivory Coast, rural tuberculosis rates by 1980 were down to 0.5 percentâa success story. But in the large capital city of Abidjan the TB rate was 3 percent and climbing.

46

These and hundreds of other examples of urban squalor and its concomitant diseases were compounded by large-scale chronic malnutrition. Except in times of famine, drought, or other natural disastersâor of the man-made disaster of warfareârural residents of even exceptionally poor countries usually had access to a variety of types of food, including protein. But when they moved to the city, people had to buy foods that were produced and marketed by others. Lacking sufficient earning power to purchase goods, the urban poor were forced to forgo adequate foods. Even in times of food plenty for the nation, most of its urban population might, as a result, be malnourished. This, of course, contributed to weakening their disease-fighting immune systems.

47

47

Other books

Twelve Days of Xanthus by Shyla Colt

Keep Me Posted by Lisa Beazley

Something About Love: A YA contemporary romance in verse by Johnson, Elana

The Class by Erich Segal

Rex Stout - Nero Wolfe 24 by Three Men Out

Twilight of the Wolves by Edward J. Rathke

Better Off Red by Rebekah Weatherspoon

Split Second (Pivot Point) by West, Kasie

The Boss's Pet: Sharing Among Friends by Kinzer, Tonya

13 Minutes by Sarah Pinborough