The Coming Plague (134 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

195

In addition to the millions of dollars spent on early malaria eradication efforts, substantial amounts of money poured into WHO control efforts and international research. Between 1973 and 1988, for example, WHO received from a variety of sources an average of $73 million annually for malaria control. Most of that was spent on training people at the local level to do such things as apply pesticides or count parasite levels in people's blood.

The U.S. government spent similar amounts of money, primarily for drug and vaccine research through either the Army or the Agency for International Development. USAID spending averaged around $22 million annually during the period; military research spending was about $10 million a year. The CDC and the NIH each spent well under $1 million a year on malaria research. See Institute of Medicine (1991), op. cit.

196

By far the majority of all dollars spent on malaria research from 1960 to 1994 were dedicated to the search for a vaccine. Though a promising product failed to appear, the effort pushed on relentlessly, amid indictments and corruption. The biggest funder was the U.S. Agency for International Development, which spent for vaccine efforts over and above other forms of possible control or drug development. As R. S. Desowitz. formerly of the University of London, then at the University of Hawaii, put it: “AID failed because it was run by amateurs who would not heed the advice of professionals. AID failed because it succumbed to sleaze and corruption. AID failed because it fostered mediocre science and over-inflated the meaning of experimental results. It may also be that AID failed because the human constitution is such that no vaccine can a confer protective immunity.” R. S. Desowitz,

The Malaria Capers

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

The Malaria Capers

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

In the spring of 1993, Colombian scientist Dr. Manuel Elkin Patarroyo announced results of a field trial of a synthesized protein vaccine against

P. falciparum.

In 1,500 Colombians the vaccine proved 38 percent effective in preventing infection, he said. A year later, amid much WHO fanfare, Patarroyo announced similar results from a field trial in Tanzania. Skeptics questioned the timing of the Tanzania announcement, which was coincident with USAID plans to cut the vaccine research budget. And they said that such claims had been made before. See “Malaria Vaccine a âGood Chance' for a Breakthrough,”

World Bank News

XIII (February 17, 1994); World Health Organization, “Malaria Vaccine Could Be Developed Soon: Global Effort Needed,” Press Release WHO/13/13 February 1994; M. V. Valero, L. R. Amador, C. Galindo, et al., “Vaccination with SPf66, a Chemically Synthesized Vaccine Against

Plasmodium falciparum

Malaria in Colombia,”

Lancet

341 (1993): 705â10; and P. Brown, “Malaria Vaccine Passes Key Test,”

New Scientist

, February 19, 1994: 7.

P. falciparum.

In 1,500 Colombians the vaccine proved 38 percent effective in preventing infection, he said. A year later, amid much WHO fanfare, Patarroyo announced similar results from a field trial in Tanzania. Skeptics questioned the timing of the Tanzania announcement, which was coincident with USAID plans to cut the vaccine research budget. And they said that such claims had been made before. See “Malaria Vaccine a âGood Chance' for a Breakthrough,”

World Bank News

XIII (February 17, 1994); World Health Organization, “Malaria Vaccine Could Be Developed Soon: Global Effort Needed,” Press Release WHO/13/13 February 1994; M. V. Valero, L. R. Amador, C. Galindo, et al., “Vaccination with SPf66, a Chemically Synthesized Vaccine Against

Plasmodium falciparum

Malaria in Colombia,”

Lancet

341 (1993): 705â10; and P. Brown, “Malaria Vaccine Passes Key Test,”

New Scientist

, February 19, 1994: 7.

197

See E. Marshal, “Malaria Parasite Gaining Ground Against Science,”

Science

242 (1991): 190â91; and P. J. Hilts, “U.S. Plans Deep Cuts in Malaria Vaccine Program,”

New York Times

, February 13, 1994: A17.

Science

242 (1991): 190â91; and P. J. Hilts, “U.S. Plans Deep Cuts in Malaria Vaccine Program,”

New York Times

, February 13, 1994: A17.

14. Thirdworldization

1

We're running scared,” Mahler told

New York Times

reporter Lawrence Altman in 1986, adding that he could”not imagine a worse health problem in this century ⦠. We stand nakedly in front of a very serious pandemic as mortal as any pandemic there has ever been. I don't know of any greater killer than AIDS.” See L. K. Altman,”Global Program Aims to Combat AIDS âDisaster,'”

New York Times

, November 21, 1986: Al.

New York Times

reporter Lawrence Altman in 1986, adding that he could”not imagine a worse health problem in this century ⦠. We stand nakedly in front of a very serious pandemic as mortal as any pandemic there has ever been. I don't know of any greater killer than AIDS.” See L. K. Altman,”Global Program Aims to Combat AIDS âDisaster,'”

New York Times

, November 21, 1986: Al.

2

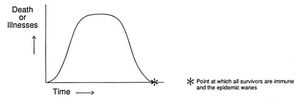

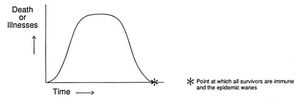

The bell-shaped curve typically seen with epidemics indicated that in any population of people infected with a given microbe, some would eventually have a natural immunity and survive, even if enormous numbers of other people died. The only other disease on earth in 1994 that similarly failed to exhibit a bell-shaped curve was rabies, which was 100 percent lethal in all people in the absence of emergency vaccination. The classic curve was pictured as follows:

In 1986 the bell was still on its upward curve everywhere in the world. In 1994 it remained so everywhere with the exception of a handful of small population groups that took preventive steps to avoid infection and an even smaller set of human beings scattered around the globe who appeared to have been infected and naturally cleared HIV from their bodies, never contracting AIDS.

3

The full extent of all WHO activities relevant to AIDS prior to establishment of the Global Programme on AIDS is outlined in the following: World Health Organization, Executive Board, Seventy-seventh Session, Provisional Agenda item 20, “WHO Activities for the Prevention and Control of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS),” EB 77/42, November 25, 1985.

4

The UN agencies were often viewed by government leaders as graceful dumping grounds for powerful foes, corrupt politicians, burned-out or less than brilliant cronies, or influential political allies who happily received payoffs in the form of cushy jobs in wealthy countries for years of successfully bolstering the power bases of their leaders. Certainly not all the 50,000 professionals employed in the UN system were of that ilk; many were bright visionaries who ardently believed in the need for a global community that sought collective solutions to its problems rather than resorting to wars. But all too often in UN history the bright and idealistic were stifled by the bureaucratic, corrupt, and dim-witted. See “The United Nations Agencies: A Case for Emergency Treatment,”

The Economist,

December 2, 1989: 23â26; R. N. Wells, Jr.,

Peace by PiecesâUnited Nations Agencies and Their Roles: A Reader and Selective Bibliography

(Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1991); G. Hancock,

Lords of Poverty

(New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1989); and V. Navarro, “A Critique of the Ideological and Political Positions of the Willy Brandt Report and the WHO Alma Ata Declaration,”

Social Science and Medicine

18 (1984): 467â74.

The Economist,

December 2, 1989: 23â26; R. N. Wells, Jr.,

Peace by PiecesâUnited Nations Agencies and Their Roles: A Reader and Selective Bibliography

(Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1991); G. Hancock,

Lords of Poverty

(New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1989); and V. Navarro, “A Critique of the Ideological and Political Positions of the Willy Brandt Report and the WHO Alma Ata Declaration,”

Social Science and Medicine

18 (1984): 467â74.

5

Fortieth World Health Assembly, Agenda item 18.2, WHA 40.26, 12th Plenary, 3 pages.

6

The statement read:

1.

CONFIRMS that WHO should continue to fulfill its role of directing and coordinating the global, urgent and energetic fight against AIDS;

CONFIRMS that WHO should continue to fulfill its role of directing and coordinating the global, urgent and energetic fight against AIDS;

2.

ENDORSES the establishment of a Special Programme on AIDS and stresses its high priority.

ENDORSES the establishment of a Special Programme on AIDS and stresses its high priority.

3.

FURTHER ENDORSES the global strategy and programme prepared by WHO to combat AIDS ⦠.

FURTHER ENDORSES the global strategy and programme prepared by WHO to combat AIDS ⦠.

and encouraged the nations of the world to openly share all germane information and cooperate in efforts to combat AIDS.

7

See Annex 2, Resolution 42/8 of the Forty-second General Assembly of the United Nations, “Prevention and Control of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS),” WHO/GPA/DIR/89.4, 1987.

8

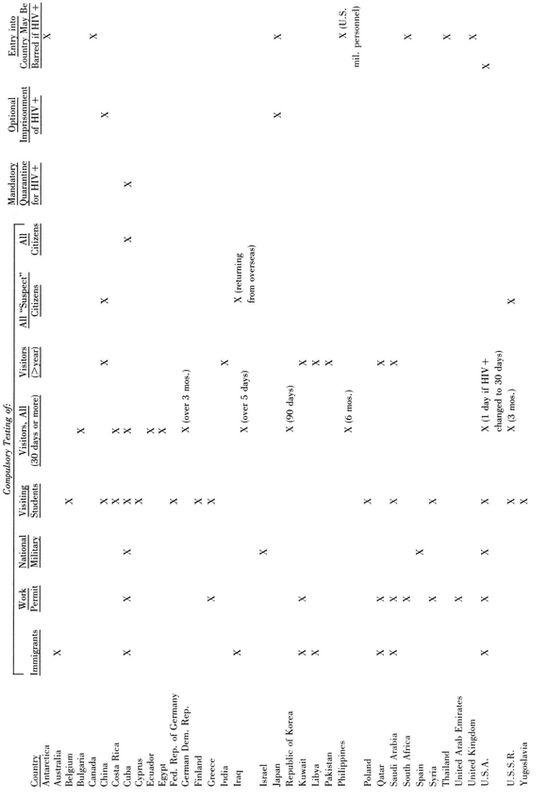

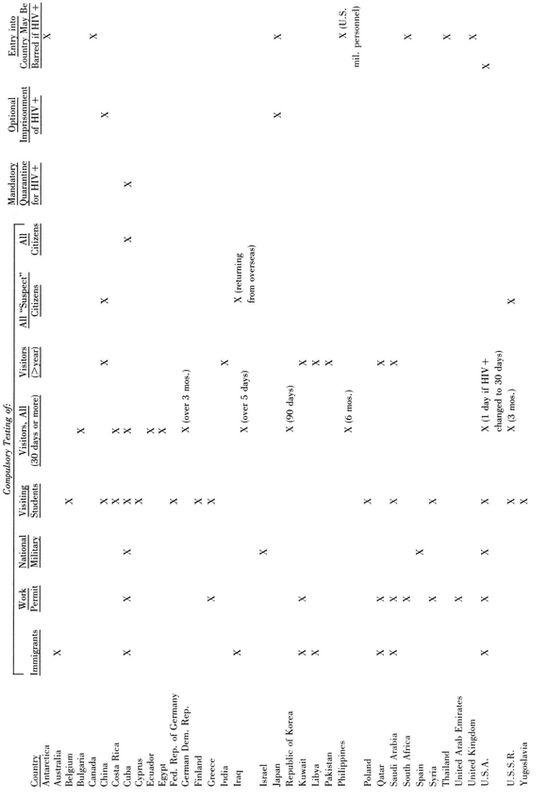

THE GROWTH OF HIV/AIDS LEGISLATION, 1983â92 (Source: World Health Organization, Health Legislation Unit)

Countries, etc., known to have legislation as of December 1983

: Austria, Canada (Alb.; B.C.; Ont.), Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Turkey, U.S.A. (CA; NJ; NY)

: Austria, Canada (Alb.; B.C.; Ont.), Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Turkey, U.S.A. (CA; NJ; NY)

Additional jurisdictions introducing legislation between 1984 and 1987

: Angola (1987), Australia (1984), Barbados (1985), Belgium (1985), Belize (1987), Benin (1987),* Bermuda (1985), Brazil (1985), Brunei Darussalam (1987), Bulgaria (1985), Burundi (1987), Canada (1985), Chile (1984), China (1987), Costa Rica (1985), Cuba (1986), Cyprus (Sovereign Base Areas) (1987), Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (1984), Denmark (1985), Dominican Republic (1987), Ecuador (1985), Egypt (1986), Finland (1985), [German Democratic Republic (1986)], Grenada (1986), Guatemala (1986), Haiti (1987), Honduras (1987), Hungary (1985), Iceland (1986), India (Goa) (1987), Indonesia (1987), Iraq (1987), Jordan (1987), Kenya (1987), Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1987), Liechtenstein (1987), Luxembourg (1984), Malaysia (1985), Malta (1986), Mauritius (1987), Mexico (1985), Monaco (1986), Mozambique (1986), Netherlands (1987), Niger (1987), Panama (1985), Paraguay (1985), Peru (1987), Philippines (1986), Poland (1986), Portugal (1986), Republic of Korea (1987), Romania (1985),* Russian Federation (1985), Rwanda (1987), Singapore (1985), South Africa (1987), Spain (1985), Switzerland (1986), Syrian Arab Republic (1987), Thailand (1985), Togo (1987), United Kingdom (1984), Uruguay (1984), Venezuela (1984), Yugoslavia (1986)

: Angola (1987), Australia (1984), Barbados (1985), Belgium (1985), Belize (1987), Benin (1987),* Bermuda (1985), Brazil (1985), Brunei Darussalam (1987), Bulgaria (1985), Burundi (1987), Canada (1985), Chile (1984), China (1987), Costa Rica (1985), Cuba (1986), Cyprus (Sovereign Base Areas) (1987), Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (1984), Denmark (1985), Dominican Republic (1987), Ecuador (1985), Egypt (1986), Finland (1985), [German Democratic Republic (1986)], Grenada (1986), Guatemala (1986), Haiti (1987), Honduras (1987), Hungary (1985), Iceland (1986), India (Goa) (1987), Indonesia (1987), Iraq (1987), Jordan (1987), Kenya (1987), Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1987), Liechtenstein (1987), Luxembourg (1984), Malaysia (1985), Malta (1986), Mauritius (1987), Mexico (1985), Monaco (1986), Mozambique (1986), Netherlands (1987), Niger (1987), Panama (1985), Paraguay (1985), Peru (1987), Philippines (1986), Poland (1986), Portugal (1986), Republic of Korea (1987), Romania (1985),* Russian Federation (1985), Rwanda (1987), Singapore (1985), South Africa (1987), Spain (1985), Switzerland (1986), Syrian Arab Republic (1987), Thailand (1985), Togo (1987), United Kingdom (1984), Uruguay (1984), Venezuela (1984), Yugoslavia (1986)

Additional jurisdictions introducing legislation between 1988 and 1992

: Albania (1992), Algeria (1989), Argentina (1988), Bahrain (1990), Bolivia (1988), China (Province of Taiwan) (1988),* Colombia (1988), Comoros (1988), El Salvador (1988), Equatorial Guinea (1988), Estonia (1992), Gabon (1989), Guinea-Bissau (1989), Hong Kong (1988), Japan (1988), Lebanon (1990), Madagascar (1990), Mongolia (1989), Oman (1990), Saint Lucia (1991), Saudi Arabia (1990), Senegal (1990), Tunisia (1989), Ukraine (1991),* Vietnam (1989)

: Albania (1992), Algeria (1989), Argentina (1988), Bahrain (1990), Bolivia (1988), China (Province of Taiwan) (1988),* Colombia (1988), Comoros (1988), El Salvador (1988), Equatorial Guinea (1988), Estonia (1992), Gabon (1989), Guinea-Bissau (1989), Hong Kong (1988), Japan (1988), Lebanon (1990), Madagascar (1990), Mongolia (1989), Oman (1990), Saint Lucia (1991), Saudi Arabia (1990), Senegal (1990), Tunisia (1989), Ukraine (1991),* Vietnam (1989)

Date of legislation unknown

: Bahamas,* Cyprus,* United Republic of Tanzania*

: Bahamas,* Cyprus,* United Republic of Tanzania*

*Text unavailable to WHO.

See chart on facing page.

9

For a flavor of the period, see Panos Dossier,

The Third Epidemic: Repercussions of the Fear of

AIDS (London: Panos Institute and Norwegian Red Cross, 1990).

The Third Epidemic: Repercussions of the Fear of

AIDS (London: Panos Institute and Norwegian Red Cross, 1990).

10

In addition, Zimmermann revealed that the names of HIV-positive German residents had been forwarded to police authorities, who were closely watching the individuals.

11

These and other details are compiled from a large variety of news, medical, and interview sources. Citing these points would so severely increase the size of this book that I must request the readers' forgiveness and refer, in addition to the previously cited Panos Dossier, to back issues of two invaluable publications:

CDC AIDS Weekly,

P.O. Box 5528, Atlanta, Georgia; and

AIDS Newsletter,

published by the Bureau of Hygiene and Tropical Diseases, London, WC1E7HT.

CDC AIDS Weekly,

P.O. Box 5528, Atlanta, Georgia; and

AIDS Newsletter,

published by the Bureau of Hygiene and Tropical Diseases, London, WC1E7HT.

12

According to a BBC translation, the Soviet decree stated:

The citizens of the U.S.S.R., as well as foreign citizens and stateless persons living or staying in the territory of the U.S.S.R., may be bound to take a medical test for the AIDS virus. If they refuse taking the test voluntarily, the persons, in relation of whom there are grounds for assuming that they are infected with the AIDS virus, may be brought to medical institutions by health authorities with the assistance in the necessary cases of authorities from the Interior Ministry.

The infection of another person with AIDS by a person aware of having AIDS shall be punishable by up to eight years in prison.

13

In fact, according to 1993 Cuban government statistics, more tests were eventually conducted than there were Cubans, meaning some people were repeat-tested. More than 14 million tests were conducted between 1986 and 1993. Some 930 Cubans would test positive during that time, according to Dr. Jorge Pérez. director of Cuba's Los Cocos AIDS sanitarium in Havana.

14

Anti-African sentiments were so high that AIDS rumors sparked mini-riots in Beijing and around universities located in other Chinese cities. Deported African students described raids upon their dormitories by citizens' groups, beatings, and tauntings when they appeared in public places.

15

For details on the evolution of the Thai sex trade and its influence on the AIDS epidemic, see Asia Watch Women's Rights Project

, A Modern Form of Slavery

(New York, Washington, Los Angeles, London: Human Rights Watch, 1994).

, A Modern Form of Slavery

(New York, Washington, Los Angeles, London: Human Rights Watch, 1994).

16

C. Decker, “Robertson Tailors His Message to Audiences,”

Los Angeles Times

. November 23, 1987: Al.

Los Angeles Times

. November 23, 1987: Al.

17

This argument generated an enormous amount of press, and no short list of citations can adequately capture the flavor of this often vociferous debate. For a hint of the atmosphere, see T. Monmaney, P. Wingert, G. Raine, and M. Gosnell, “AIDS: Who Should Be Tested?”

Newsweek,

May 11, 1987: 64â65; M. Cimons, “Candidates Forced to Deal with AIDS Issue,”

Los Angeles Times,

November 2, 1987: Al; M. Cimons, “Bowen Against Federal AIDS Legal Protection,”

Los Angeles Times,

September 22, 1987: A16; R. Shilts, “U.S. Backtracks on AIDS Brochure,”

San Francisco Chronicle

,

August

28, 1987: Al; C. Thomas, “Fight AIDS with a National Health Card,” Editorial,

Los Angeles Times,

May 5, 1987; M. Cimons, “Conservatives Split as Some Attack Koop,”

Los Angeles Times,

May 14, 1987: Al; D. Whitman, “A Fall from Grace on the Right,”

U.S. News & World Report

, May 25, 1987: 27â28; J. Helms, “Only Morality Will Effectively Prevent AIDS from Spreading,” Editorial,

New York Times,

November 23, 1987; and C. E. Koop,

Koop: Memories of America's Family Doctor

(New York: Random House, 1991).

Newsweek,

May 11, 1987: 64â65; M. Cimons, “Candidates Forced to Deal with AIDS Issue,”

Los Angeles Times,

November 2, 1987: Al; M. Cimons, “Bowen Against Federal AIDS Legal Protection,”

Los Angeles Times,

September 22, 1987: A16; R. Shilts, “U.S. Backtracks on AIDS Brochure,”

San Francisco Chronicle

,

August

28, 1987: Al; C. Thomas, “Fight AIDS with a National Health Card,” Editorial,

Los Angeles Times,

May 5, 1987; M. Cimons, “Conservatives Split as Some Attack Koop,”

Los Angeles Times,

May 14, 1987: Al; D. Whitman, “A Fall from Grace on the Right,”

U.S. News & World Report

, May 25, 1987: 27â28; J. Helms, “Only Morality Will Effectively Prevent AIDS from Spreading,” Editorial,

New York Times,

November 23, 1987; and C. E. Koop,

Koop: Memories of America's Family Doctor

(New York: Random House, 1991).

18

For a flavor of the U.S. immigration debate, see R. M. Wachter,

The Fragile Coalition

(New York: St. Martin's Press, 1991).

The Fragile Coalition

(New York: St. Martin's Press, 1991).

19

The distinction between “epidemic” and “endemic” is crucial to all discussion of emerging diseases. Ideally, one hopes to spot an emerging microbe and bring it under control when its impact on

Homo sapiens

is limited to small outbreaks. Barring that, there may still be hope for effective action against an epidemic, which, by definition, is a new and potentially short-lived phenomenon.

Homo sapiens

is limited to small outbreaks. Barring that, there may still be hope for effective action against an epidemic, which, by definition, is a new and potentially short-lived phenomenon.

With microbes like HIV, human papillomavirus, and herpes simplex, it was very difficult to spot emergence at either the outbreak or early epidemic stages because the majority of infected human beings were asymptomatic for months or years. Thus, an epidemic could smolder and spread, unnoticed, for years. Slow-acting viruses offered the greatest challenge to public health advocates, therefore, because it took so long for the public to recognize a threat.

In the absence of alert public health authorities, such simmering epidemics could easily evolve into endemic diseases in a society before the emergence of the microbe was even noticed. Once a disease was endemic to some segment of a society, it was extremely difficult to defeat.

The GPA hoped in 1988 to prevent HIV from becoming endemic to most of the societies in the world by shaking governments out of denial and prompting effective action while HIV was still in an outbreak or early epidemic stage of emergence. By 1988 endemicity was already the reality in much of sub-Saharan Africa, North America, and Western Europe. But there was hope for the majority of the world's populations, residing in Asia, Eastern Europe, Oceania, and Latin America.

Â

AIDS-RELATED RESTRICTIONS ENACTED INTO LAW AT FEDERAL LEVELS, 1987â89*

(Compiled from multiple sources, including WHO; Panos Institute; McGill Centre for Medecine, Ethics and Laws; AIDS Policy Center. Intergovernmental Health Policy Project, George Washington University) * Some of these laws were subsequently revoked. In addition, some countries passed analogues legislation or edicts after 1989).

(Compiled from multiple sources, including WHO; Panos Institute; McGill Centre for Medecine, Ethics and Laws; AIDS Policy Center. Intergovernmental Health Policy Project, George Washington University) * Some of these laws were subsequently revoked. In addition, some countries passed analogues legislation or edicts after 1989).

In a worst-case scenario HIV would reach endemic status on one or two continents, spread as a pandemic across the rest of the world, and eventually reach a stage of global endemicity, becoming permanently entrenched in every society on earth.

Other books

Worth a Thousand Words by Noel, Cherie

The Pregnancy Test by Erin McCarthy

The Hands of Time by Irina Shapiro

Breathless & Bloodstained (The Chicago War #4) by Bethany-Kris

Set Me Free by Gray, Eva

Getting Married by Theresa Alan

Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden

Einstein's Monsters by Martin Amis

Mr. Darcy's Great Escape by Marsha Altman

Dear Opl by Shelley Sackier