The Black Pearl (8 page)

Authors: Scott O'Dell

"The pearl is gone," he cried. "Gone!"

"Gone?" I asked.

"Stolen!"

I jumped to my feet and followed him back to the church. People were gathering outside. He led me down the aisle and pointed to the niche where the Madonna stood with Her hand held out and empty. A crowd had followed us and there were many ideas about who had stolen the great pearl. Someone said that an Indian she knew had stolen it. Another said he had seen a strange man running away from the church.

As I listened and the women wept and Father Gallardo wrung his hands, it was on my tongue to say, "I have the pearl. It is in my room, hidden under my pillow. Wait and I will get it." Then I thought of the wrecked ships at Maldonado and again I heard the old man's voice, as clear as if he were there in the church beside me, speaking his solemn admonition.

I slipped away and went home and after supper, with the pearl hidden in my shirt, I went down to the beach, taking a roundabout path so as not to be seen. I searched until I found a

boat that belonged to a man I knew. It was not a boat for a swift voyage, being too large for me to handle well, but there were no others.

When the moon came up I started for the lagoon where the Manta Diablo lived, or where the old man said he lived, and now I half-believed to be the truth.

A

BOUT DAWN

I reached the entrance to the lagoon. The tide was out but it had started to change and I had trouble steering the boat down the dark channel.

As I came to the rocks that guard the cave, I found that the lagoon lay hidden under a mantle of red mist, so heavy that the far shore where the old man lived could not be seen. It was then that I heard a sound. Perhaps I heard nothing and only felt that someone or something was behind me.

During the long night I had thought little of the Manta Diablo and when I did it was without fear. A creature who could change his form and become a living person and go into the town and even into the church, as the old man said, whose friends among the sharks and fish told him everything they saw or heard on the sea, surely this creature would know that I had the great pearl and was returning it to his cave. Still from time to time, as I rowed southward in the night, I scanned the moonlit waves for the monstrous, batlike form, half-smiling as I did so.

Behind me in the mist I heard the sound again. Then above the hissing of the tide came a voice I knew at once.

"Good morning, mate," he said. "But you are slow with the oars. I followed you out from La Paz and dawdled most of the night and waited and fell asleep. Does the pearl weigh you down?"

"What pearl?" I asked, calmly as I could.

The Sevillano laughed. "The great one, of course," he said. "Listen and let us be truthful. I know that you stole the big one. I stood at the door and saw you steal it and I also saw the bulge in your pocket when you came out from the church. Since we are truthful and you will wonder why I watched you I must say that I was there because I came to steal the pearl myself. Does that surprise you?"

"No," I said.

"Two thieves," the Sevillano said and laughed again. "Now that we both speak the truth as thieves, do you have the pearl?"

I could not see him through the heavy mist nor could I judge where his boat was.

"And if you do not have the pearl," he said, "then tell me, is this where you found it?" His voice became hard. "To both these questions, give me a truthful answer."

Now the red mist parted a little where we were floating and the sun broke through. The Sevillano was between me and the mantas cave, much closer than I had thought him to be. In his hand was a knife and the sun glittered on it. We looked at each other and I saw by his face that he meant to use the knife if the need arose; still I said nothing.

"Do not think that I blame you for stealing the great pearl," he said. "For all the good it did it might better have been given to the devil. Nor do I blame you for wishing to keep the place where you found it a secret. But hand it over, mate, and we shall talk then about other things."

He put the knife in his belt. His boat moved nearer, until it touched the prow of mine. He held out his hand to take the pearl.

The cave was dark, yet not far distant, so I could see it clearly. I took the pearl from my

shirt, as if to give it to him, but as he put out his hand to receive it, I threw the pearl into the air, beyond him into the water, into the mouth of the cave.

It was an unwise thing to do, for the pearl had no quicker left my hand than the Sevillano was in the sea, swimming beneath the water. I picked up the oars and turned the heavy boat against the current, thinking that I would row to the far end of the lagoon and seek the old man's help. Before I could straighten the boat, the Sevillano came to the surface, grasped one of the oars and then the gunwale. In his hand was the great black pearl.

"You toss it to the devil and the devil picks it up," he said, climbing over the side. "Now we find my boat."

It had drifted off on the tide. The boat was smaller than mine and as we overtook it I saw that it was filled with provisions for a voyageâfood, a jug of water, a fishing line and hooks, and an iron harpoon, among other things. The Sevillano stepped into the boat and motioned me to follow. Not knowing what he meant for me, I did not move.

"Hurry, mate, or we miss the tide," he said. "We have many leagues to go."

"I am rowing ashore," I answered him. "I have business with Soto Luzon."

The Sevillano slipped the knife from his belt. I looked toward the far shore and hoped that the old man had heard our talk and had come to the lagoon to see who we were, but the red mist still hid the shore from view.

Again the Sevillano motioned me into the boat, this time with his threatening knife. I had no choice except to obey him.

"Sit down. Be comfortable," he said, handing me a pair of oars.

He stripped off his singlet and wrapped it round the pearl and seated himself in back of me.

"Row," he said.

The mist had begun to rise from the water. I took a last look toward the shore, but it was deserted. Then I felt the sharp point of the knife pressing against my shoulder. I picked up the oars and began to row aimlessly.

"Toward the sea," the Sevillano said. "Because we go in that direction. And why do we go in that direction? Since you will ask this sooner or later, I shall tell you now. We go to the City of Guaymas. What do we there? We sell the great pearl. We sell it together, you and I, for the name of Salazar is known among the pearl dealers of Guaymas. And for this reason we shall sell it for ten times the sum I could get if I sold it alone."

He was silent, busying himself with his oars. I heard him set the oars in their locks and thought, Now there is a chance for me to slip over the side and swim to the nearest shore. He must have read my thoughts, for again I felt the knife pressing against my back.

"Since I cannot row and watch at the same time," he said, "it is you who must do the rowing, so put your mind to it, mate. The tide turns and does not wait."

Slowly I pulled at the oars, thinking a hundred thoughts in desperation. But to no avail, for the knife was at my back and I could only do what I was bidden.

Once outside the channel, too far for me to swim ashore, the Sevillano set his course eastward across the Vermilion and raised a ragged sail.

T

HE WIND BLEW

fresh from the south and we made a goodly distance that morning. At noon we ate some of the corn cakes the Sevillano had brought and then I lay down and slept. When I awoke at dusk I asked the Sevillano if he wished me to take the tiller while he slept.

"No," he said and grinned. "I have little trust in you, mate. I might never wake up and if I did I would most likely find that you had turned the boat around and we were sailing back into La Paz."

Nevertheless, the Sevillano did doze off, but with one eye open and a hand on his knife and the pearl held between his bare feet, which had long toes like fingers.

The wind slackened and as the moon came up I saw a movement on the sea, some two furlongs astern. It was not a wave that I saw because the sea was smooth. There were many sharks around, so I thought that a few of them were feeding upon a school of fish. Shortly I saw the movement again and this time the moon's light shone on the tips of outspread wing-like fins, rising and slowly falling. It was plainly a manta.

We had seen several of these creatures that day, sunning themselves or leaping high into the air out of good spirits, therefore I paid no heed to the one swimming behind us. I fell asleep and awoke about midnight to sounds that I felt I had dreamed.

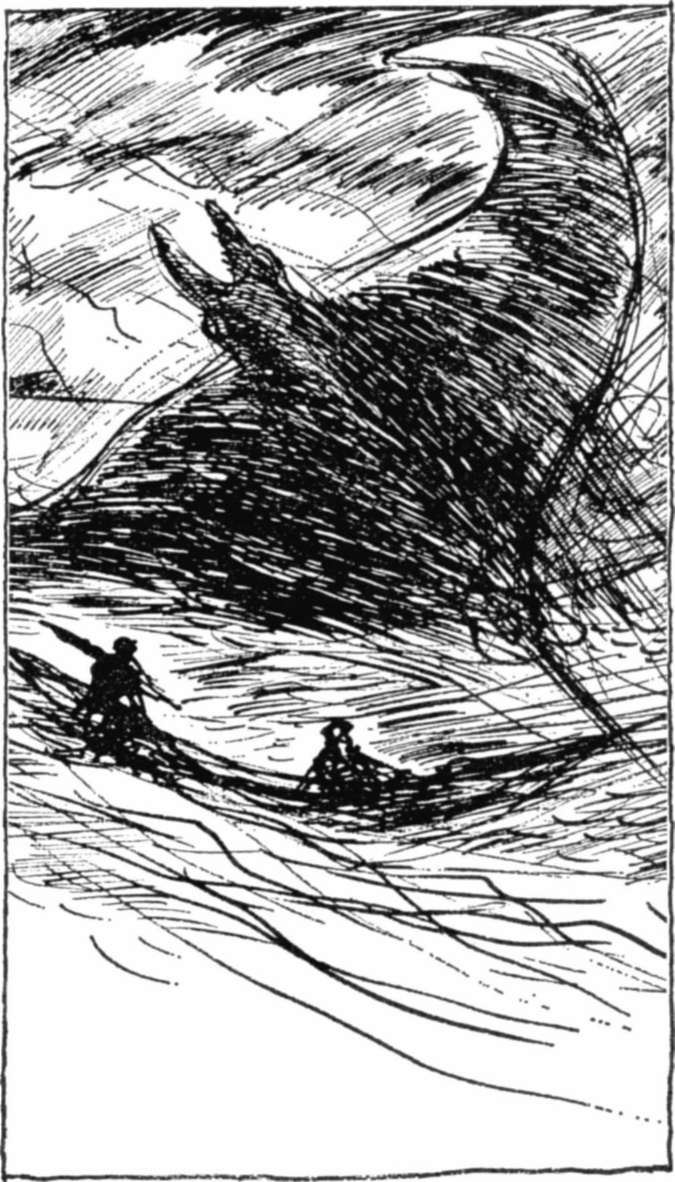

The sounds were small and not far distant, like the sounds that wavelets make as they slide upon a beach. Suddenly I found that they were nothing I had dreamed, for not more than a hundred feet away and clear in the moonlight a giant manta was swimming along behind us.

"We have a companion," I said.

"A big one," replied the Sevillano. "I wish he would swim out in front and then I could tie a rope to him and we would soon be in the City of Guaymas."

He laughed at the picture he had called up, but I sat silent and stared at the giant manta swimming close to the stern of our boat. That it was the same manta I had seen early in the evening, I had no doubt.

"He smells the corn cakes," said the Sevillano.

At daylight the manta still swam behind us. He was no closer than before, swimming along at the same pace as the boat, with only the slightest movement of his fins, more like a giant bat swimming through the air than like a fish.

"Remember on the voyage," I said to the Sevillano, "when we were coming home and you shouted, 'Manta Diablo,' and the Indian got scared? Well, he should be here now to see this one."

"I have seen many," said the Sevillano, "but this one is the monster of all. He will measure ten paces across, from fin to fin, and weigh more than two ton. But they are a chummy sort, these sea-bats, friendly like the dolphins. I have had them follow my boat for a whole day, yet never with malice. Still, with a mere flip of a fin or a twitch of their tail they can send you into eternity.

Most of an hour went by and then the manta swam out ahead of us. As he passed the boat, I clearly saw his eyes. They were the color of amber and flecked with black spots and they seemed to fix themselves upon me and me alone, not upon the Sevillano. I also caught a glimpse of his mouth and for some reason remembered that my mother had told me that the Manta Diablo had seven rows of teeth, and I said to myself, "She was wrong, he has no teeth above and only one set below, which is dull and not sharp like knives and very white."

The manta turned and came back, swimming in a wide circle around us. Then out he went again, but this time when he returned the circle was smaller and the waves he made caused the boat to pitch about.

"I grow tired of our friend," said the Sevillano. "If he swims closer I will give him a taste of the harpoon."

I wanted to say to the Sevillano, "You had best not molest him. One harpoon would be only the prick of a pin." I tried to say, "This is not just a manta that swims there. This is the Manta Diablo." But my lips were frozen.

I think it was the amber eye he had fixed upon me as he passed, upon me and not upon the Sevillano. Yet it might have been the stories that had frightened me as a child, before I had learned to laugh at them, that now came flooding back, more real than they ever were. I do not know. I do know that suddenly I was certain that the giant swimming there was the Manta Diablo himself.

The circles grew smaller. We were the center of themâthe boat, the Sevillano, myself, the pearlâof this I had no doubt.

The boat began to rock violently and water came in and we both had to bail with our hats to save it from sinking. A half mile or less off our bow was an island called Isla de los Muertos, Island of the Dead. It had gained this name because on it lived a tribe of Indians who were known to do away with all those who landed there, to spear turtles or for any other reason.

"Keep at the bailing and I will row," said the Sevillano. "We head for the island."

"I would rather take my chances on Los Muertos," I said and never in my life meant anything more.

As if he sensed what we planned to do, the Manta Diablo swam off to a distance, sank out of sight, and allowed us to reach the island safely.

L

OS

M

UERTOS

is barren like all the islands of our Vermilion Sea, but it has a snug, sandy cove where turtles by the hundreds come to lay their eggs. Into this we made our way, beached the boat, and then climbed a low hill behind the cove, which gives a good view of the island.

Isla de los Muertos is small and mostly flat and at its southern end the Indians live out in the open, without shelters of any kind. From the hill we saw that evening fires were burning and people had gathered around them and that their black canoes lay in a neat row on the shore. We decided, therefore, that no one had seen us sail into the cove.

We turned the boat over and emptied the water that had almost swamped us and ate more of the corn cakes. By then it was night.