The Big Burn (21 page)

Authors: Timothy Egan

The chain reaction of a wildfire had begun. Heated plant matter released hydrogen and carbon while drawing in oxygen, and the whole of it was on the run, a weather system of its own. Thus, three small blazes in grass met six bigger ones in the lower forest and then merged with a dozen others before joining twenty or thirty more, until the mass was bundled into a single wall of yellow and orange moving upward at fifty miles an hour into the crowded zone of Douglas fir, spruce, and larch, into groves of wizened hardwoods and withered cedars next to dried-up streams, moving faster than a horse could run. All at once, it burned at the scrub and limbs of the lower tier of the forest, it burned at thick midheight, it burned large boughs, which broke away in the storm, huge cones popping in fireballs, and it burned at the crowns, the highest tips of the trees exploding into the air, flying off to light the crowns of other tall trees. The densest part of the forest, between three and five thousand feet above sea level, was ready-to-burn fiber when the flames

moved through it. In pops and cracks and snaps and gulps, in gasps and whistles, the fire metastasizedâmore clamorous with every fresh intake, charging ahead. Any leftover little fire that might have smoldered and smoked in a last gasp was given new life by the wind, yanked from the ground, pitched into the river of flame, into the current of the now unrecognizable Palouser.

Midway through the Clearwater, the wall of flame took over the forest, hundreds of feet high, at least thirty miles wide in some parts, and still gaining strength, still fanning out, consuming oxygen in heaves, and picking up intensity as its core temperature rose. The fire was a classic convection engine now: heat rising, pulling the hottest elements upward, a gyro of spark and flame. After racing through the Clearwater and Nez Perce forests, leveling nearly all living things in the Kelly Creek region, the fire swept up trees at the highest elevations. At this altitude, along the spine of the Bitterroots, the wind moved without obstruction, and the fire itself threw brands ten miles or more ahead of the flame front. The storm found the Montana border and spit flames down into the heavily settled Bitterroot Valley. It found the Lolo forest and crossed over the pass and along the summits, jumping ridgeline to ridgeline. At the peak of its power, it found the Coeur d'Alene forest, leading with a punch of wind that knocked down thousands of trees before the flames took out the rest of the woods. By now, the conscripted air was no longer a Palouser but a firestorm of hurricane-force winds, in excess of eighty miles an hour. What had been nearly three thousand small fires throughout a three-state region of the northern Rockies had grown to a single large burn.

The advance force of the firestorm, just ahead of the flame wall, was so strong it uprooted bark-armored trees that had held to a piece of ground for three centuries or more. Entire sections of the forest were mowed down as if they were blades of grass. Deer were trapped by falling timbers; some were crushed, others suffocated. Smaller animals emerged from shelter in the hollows of trees, driven out by heat and smoke, only to die in the collapsing forest.

Funnels, columns, and whirlwinds formed within the storm, each breaking out in a separate dance of gas and flames. Explosions and the charge of the wind brought a sound that shook any leaf or limb not consumed by flame.

Through the Coeur d'Alene that night, the burn picked up every fire along the ridge separating Wallace from Avery, every fire in the upper reaches of the St. Joe, and every fire downriver. Its only imperative was to find more fuel. It moved west, downstream, toward the towns of St. Maries and Coeur d'Alene and close to Spokane, and it moved east, up the Bitterroots, toward Grand Forks and Taft, over the divide, toward Missoula. It moved northeast, into the Cabinet and Pend Oreille forests, across the Canadian border into British Columbia, and farther still to Glacier Park and the Blackfeet and Flathead forests. Firebrands were tossed ten miles or more, torching the ground ahead of the incendiary waves. As the storm approached a piece of untouched ground, it announced itself with a roar and a light on the horizon and finished with a sea of flames, suffocating the woods. If there was a river in the way, the fire leapt over water. If there was a lake in the way, it rode its own wind to the other side and alighted on fresh timber. If there was a town in the way, it engulfed it without blinking, exploding a barrel of kerosene or a tank of oil, taking tents and timber, taking shellacked houses and plank sidewalks and cedar-shake churches, all ready for the burn.

The aftermath, in the Bitterroot Mountains of Idaho, of what historians have called the largest wildfire in American history.

US. Forest Service

A 1910 photo of Ed Pulaski, whose actions saved many lives. Badly wounded by the fire, he retired a bitter man.

U.S. Forest Service

This tunnel above Wallace, Idaho, is where Ranger Pulaski and his crew took refuge on the night the forest blew up under hurricane-force winds, August 20, 1910.

U.S. Forest Service

Ranger Joe Halm (right) after the fire. Halm was hired just out of college, and like Ranger Pulaski, he helped save many lives.

U.S. Forest Service

A forest in ruins. Winds knocked down trees that had held to the ground for two centuries or more, and fire left others standing, but stripped of all green.

U.S. Forest Service

Men standing amid downed timber after the Big Burn of 1910. The fire covered an area the size of Connecticut.

U.S. Forest Service

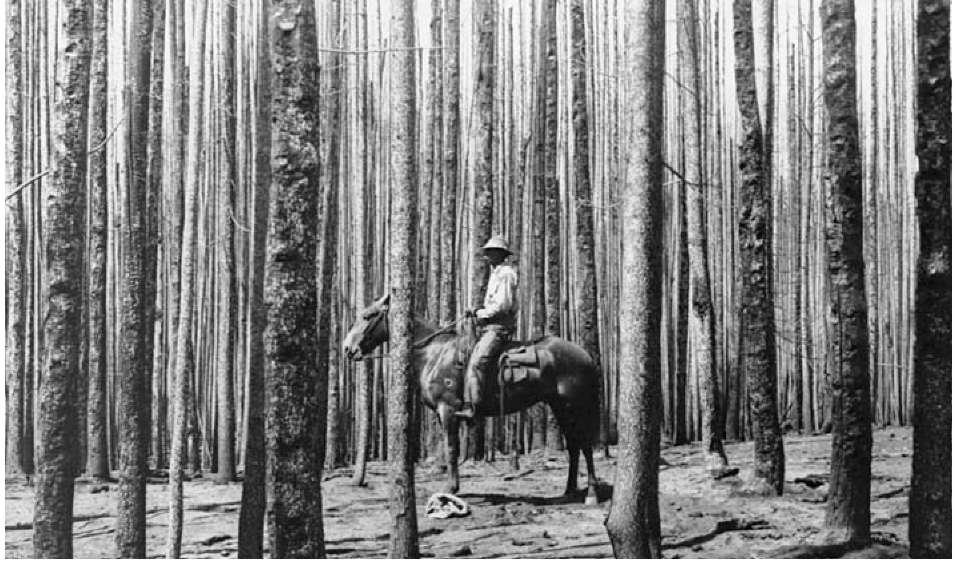

On horseback, a forest ranger patrolled the blackened and still forest in the first days after the fire. Smoke from the Big Burn drifted as far east as Chicago.

U.S. Forest Service

Burned, bandaged, and dazed, two firefighters posed for a studio photo in Wallace, Idaho, just days after the Big Burn. Many of the men who fought the blaze were immigrants or out-of-work city dwellers who knew nothing of fighting wildfires.

Barnard-Stockbridge Studio Collection, University of Idaho Library