Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (52 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

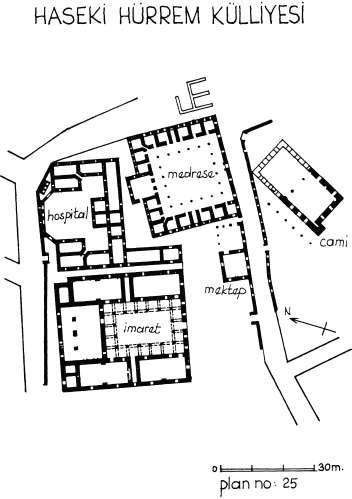

The hospital is behind the medrese, entered from the street behind the külliye to the north. It is a building of most unusual form: the court is octagonal but without a columned portico. The two large corner rooms at the back, whose great domes have stalactited pendentives coming far down the walls, originally opened to the courtyard through huge arches, now glassed-in; with these open rooms or eyvans all the other wards and chambers of the hospital communicated. Opposite the eyvans on one side is the entrance portal, approached through an irregular vestibule, like that so often found in Persian mosques. On the other side are the lavatories, also irregular in shape; while the eighth side of the courtyard forms the façade on the street with grilled windows. This building too has been well restored and is once again in use as a hospital.

Returning to the street outside Haseki Hürrem Camii, we continue on in the same direction for about 400 metres. Then to our left, set back from the road and partly concealed by trees and houses, we see a fine but dilapidated old mosque. This is Davut Pa

ş

a Camii, dated by an inscription over the door to A.H. 890 (A.D. 1485). Davut Pa

ş

a, the founder, was Grand Vezir under Sultan Beyazit II. In plan the mosque belongs to the simple type of the square chamber covered by a large blind dome; but the mihrab is in a five-sided apse projecting from the east wall and to north and south are small rooms, two on each side, once used as tabhanes for travelling dervishes. What gives the building its distinction and harmony, however, is the beautiful shallow dome, quite obviously less than half a hemisphere. The pendentives of the dome are an unusually magnificent example of the stalactite form, here boldly incised and brought far down the corners of the walls. Unfortunately they are in very bad condition, as is the interior in general. A small amount of very careful restoration is called for, for this mosque is one of the half-dozen of the earliest period which are most worthy of preservation. In fact, the five-domed porch, which was partially in ruins, has now been well restored; let us hope the interior will soon be too.

Behind the mosque a delightfully topsy-turvy graveyard surrounds the founder’s türbe, octagonal in form and with an odd dome in eight triangular segments. Across the narrow street to the north stands the medrese of the külliye, almost completely surrounded and concealed by houses. The courtyard must have been extremely handsome – indeed it still is – with its re-used Byzantine columns and capitals, but it is in an advanced state of ruin. Here immediate restoration is urgently needed to save it before it is too late, for this is the only one of the fifteenth-century vezirial medreses which survives in something like its original form. The külliye once also had an imaret and a mektep, but these have completely disappeared.

Some 200 metres beyond Davut Pa

ş

a Camii and on the same side of the street, we come to a grand and interesting complex, that of Hekimo

ğ

lu Ali Pa

ş

a. This nobleman was the son

(oglu)

of the court physician

(hekim)

and was himself Grand Vezir for 15 years under Sultan Mahmut I. A long inscription in Turkish verse over the door gives the date of construction as A.H. 1147 (A.D. 1734–5); the architect was Ömer A

ğ

a. One can consider this complex either the last of the great classical buildings or the first of the new baroque style, for it has characteristics of both. At the corner of the precinct wall beside the north entrance is a very beautiful sebil of marble with five bronze grilles; above runs an elaborate frieze with a long inscription and fine carvings of vines, flowers and rosettes in the new rococo style that had recently been introduced from France. The façade of the türbe along the street is faced in marble, corbelled out towards the top and with a çe

ş

me at the far end. It is a large rectangular building with two domes dividing it into two equal square areas. This form was not unknown in the classical period – compare Sinan’s Pertev Pa

ş

a türbe at Eyüp (see Chapter 18); but it was rare and the use of it here seems to indicate a willingness to experiment with new forms. Farther along the precinct wall stands the monumental gateway with a domed chamber above; this was the library of the foundation. Though the manuscripts have been transferred elsewhere, it still contains the painted wooden cages with grilles in which they were stored; an elegant floral frieze runs round the top of the walls and floral medallions adorn the dome. From the columned porch at the top of the steps leading to the library, one commands a good view of the whole complex, with its singularly attractive garden full of tall cypresses and aged plane trees, and opposite the stately porch and very slender minaret of the mosque.

The mosque itself, raised on a substructure containing a cistern, is purely classical in form. Indeed its plan is almost an exact replica of that at Cerrah Pa

ş

a, which we saw earlier on this tour. In contrast to that, the present building is perhaps a little weak and effeminate; there is a certain blurring of forms and enervating of structural distinctions, an effect not mitigated by the pale colour of the tile revetment. The tiles are still Turkish, not manufactured at Iznik as formerly, but at the recently established kilns at Tekfur Saray. All the same, the general impression of the interior is charming if not exactly powerful. There is a further hint of the new baroque style in one of its less pleasing traits in some of the capitals of the columns both in the porch and beneath the sultans loge. The traditional stalactite and lozenge capitals have been abandoned there in favour of a very weak and characterless form, such as an impost capital which seems quite out of scale and out of place. The whole complex within the precinct wall has been very completely and very well restored. Outside the precinct, across the street to the north-east, stands the tekke of the foundation, but little is left of it save a very ruinous zaviye, or rooms for the dervish ceremonies.

We now walk back to the intersection we passed just before we reached the mosque. There we turn left into Yapra

ğ

ı

Soka

ğ

ı

, which after the first intersection becomes S

ı

rr

ı

Pa

ş

a Soka

ğ

ı

. Just before the first turning on the left we come to a Greek church surrounded by a walled garden. This is the church of the Panaghia Gorgoepikoos, the Virgin Who Answers Requests Quickly. The church is referred to as early as 1343, and it is mentioned in Tryphon’s list of 1583. The present building dates from the early nineteenth century.

We turn left at the corner beyond the church, and then after the next intersection we see on our right the ruins of a once handsome medrese. It was built by Sinan for Ni

ş

anc

ı

Mehmet Bey, who served as Keeper of the Royal Seal (Ni

ş

anc

ı

) for Süleyman the Magnificent. The medrese was built before 1566 when Mehmet Bey died on hearing the news of Süleymans death.

At the corner beyond the medrese we turn right on Köprülüzade Soka

ğ

ı

, which after three blocks brings us to the south-west corner of an enormous open cistern on the summit of the Seventh Hill. This is the third and largest of the extant Roman reservoirs in the city, that of St. Mocius, so called from a famous church dedicated to that saint, a local martyr under Diocletian. It is a rectangle 170 by 147 metres, or just under 25,000 square metres in area. Constructed under the Emperor Anastasius (r. 491–518), it fell into disuse in Byzantine times; like the other two Roman reservoirs it served as a vegetable garden and orchard, with a few wooden houses at the eastern end. In 1993 it was converted into the Fatih Educational Park.

Returning to Hekimo

ğ

lu Ali Pa

ş

a Camii, we take the street that runs past the northern side of the mosque precinct. We follow this to its intersection with Koca Mustafa Pa

ş

a Caddesi; then we take the street opposite and slightly to our left; this immediately brings us to a pathetic ruin which is of interest only because of its association with the great Sinan.

ISA KAPI MESC

İ

D

İ

This complex consists of two walls of a Byzantine church and the wreck of a medrese by Sinan. Of the church only the south and east walls remain. It was of the simplest kind; an oblong room without aisles ending at the east in a large projecting apse and two tiny side apses. In the southern side apse there could be seen till recently the traces of frescoes; these have now almost entirely disappeared. The building is probably to be dated to the beginning of the fourteenth century, but nothing is known of its history nor even the name of the saint to whom it is dedicated. About 1560 the church was turned into a mosque by the eunuch Ibrahim Pa

ş

a, who added to it a handsome medrese designed by Sinan. Both church and medrese were destroyed by the great earthquake of 1894 and have remained abandoned ever since. The ruins of the medrese, which is unusual in plan, are rather fine; its large dershane still bears traces of plaster decoration around the dome, and the narrow courtyard beyond must have been very attractive. The medrese, known as Isa Kap

ı

Mescidi, is now under restoration. The name Isa Kap

ı

s

ı

means the Gate of Christ and the theory is that it preserves the memory of one of the gates in the city walls of Constantine the Great which are thought to have passed close by. This is possible, but the arguments of the authorities are contradictory and inconclusive.