Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (36 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

We now come to Atatürk Bulvar

ı

, the broad highway which leads from the Atatürk Bridge up the valley between the Third and Fourth Hills. We turn left here and about 300 metres along on the left we come to a rather handsome baroque mosque,

Ş

ebsafa Kad

ı

n Camii. This was built in 1787 by Fatma

Ş

ebsafa Kad

ı

n, one of the women in the harem of Abdül Hamit I. It is of brick and stone; the porch has an upper storey with a cradle-vault and inside there is a sort of narthex also of two storeys, covered with three small domes. These upper storeys form a deep and attractive gallery overlooking the central area of the mosque, which is covered by a high dome resting on the walls. To the north of the mosque is a long mektep with a pretty cradle-vaulted roof.

Directly across the avenue from the mosque you can see a huge retaining wall whose lower part contains a row of arched niches. This is a huge cistern that was part of the monastery of the Pantocrator, built by the Emperor John II Comnenus in the second quarter of the twelfth century on the Fourth Hill above the present avenue.

The whole area above the mosque on the east side of Atatürk Bulvar

ı

is occupied by the Istanbul Drapers’ and Furnishers’ Bazaar, a complex of modern shops and offices built in the years 1959–66 by the Municipality. The general conception shows more imagination than one expects to find in a municipal project, but it does not seem quite to come off in detail. Large blank surfaces from place to place are enlivened by panels of mosaics and ceramics in abstract designs done by such leading modern artists of Turkey as Bedri Rahmi Eyübo

ğ

lu and the ceramist Füreya.

In the centre of this shopping-centre we come upon an ancient little graveyard which has recently been restored. Among the tombstones there we see one bearing the name of Kâtip Çelebi (1609–58). Kâtip Çelebi, one of the most enlightened scholars of his age, was the author of at least 23 books, along with many shorter treatises and essays. His last and best known work was

The Balance of Truth

, where he writes of the beatific vision in which the Prophet inspired him to go on with his work. This reminds one of Evliya Çelebi and the remarkable vision which he had in the mosque of Ahi Çelebi, some 500 metres removed from Kâtip Çelebi’s grave and three decades earlier in time. What a town Ottoman Stamboul must have been in those days, to inspire visions such as theirs.

PRIMARY SCHOOL OF ZENBELL

İ

AL

İ

BABA

We now cross Atatürk Bulvar

ı

and take the stepped pathway beside the road which winds uphill directly opposite the mosque. A short distance up the hill, at the second turning, we find a small mektep in a walled garden. The mektep has recently been restored and is now used as a children’s library; it is a very pleasing example of the minor architecture of the early sixteenth century. It was built by the

Ş

eyh-ül Islam Ali bin Ahmet Efendi, who died in 1525

.

The founder is buried beneath a marble sarcophagus which stands in the mektep garden.

THE CHURCH OF THE PANTOCRATOR

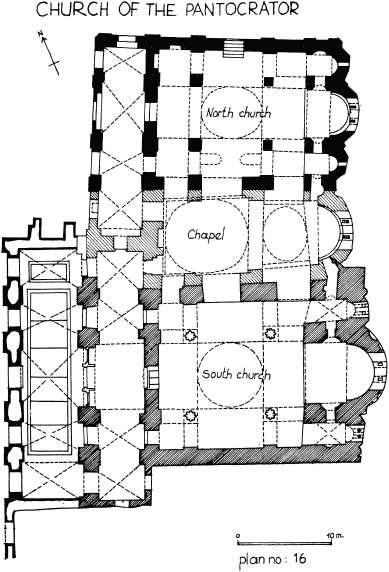

Taking the street to the right past the entrance to the mektep, we come almost immediately to a picturesque square lined on three sides with old wooden houses. On the eastern side of the square we see the former monastery church of the Pantocrator, known locally as Zeyrek Camii. The Pantocrator is a composite building consisting of two churches and a chapel between them; the whole complex was built within a period of a few years, between about 1120 and 1136. The church was converted into a mosque soon after the Conquest by Molla Mehmet Zeyrek and came to be called Zeyrek Camii. The mosque is now confined to the south church.

The monastery was founded and the south church built by the Empress Eirene, wife of John II Comnenus, some years before her death in 1124; it was dedicated to St. Saviour Pantocrator, Christ the Almighty. In plan the church is of the four-column type, with a central dome, a triple apse, and a narthex with a gallery overlooking the nave. (The columns have as usual been removed in Ottoman times and replaced by piers.) This church preserves a good deal of its original decoration, including the marble pavement, the handsome doorframes of the narthex, and the almost complete marble revetment of the apse. Work by the Byzantine Institute has brought to light again the magnificent

opus sectile

floor of the church itself, arranged in great squares and circles of coloured marbles with figures in the borders. One of these, which the imam of the mosque will uncover, is a panel tentatively identified as one of the labours of Samson. Notice also the curious Turkish mimber made from fragments of Byzantine sculpture, including the canopy of a ciborium. One of these spolia has been identified as a sculptural fragment from the church of St. Polyeuktos, whose ruins we will see later on this itinerary. The investigations of the Byzantine Institute discovered also fragments of stained glass from the east window, which seem to show that the art of stained glass was a Byzantine rather than a western discovery.

After Eirene’s death her husband John decided to erect another church a few metres to the north of hers, dedicated to the Virgin Eleousa, the Merciful or Charitable. It is somewhat smaller but of essentially the same type and plan as Eirene’s church, and here again the columns have been replaced by piers. When this church was finished, the idea seems to have struck the Emperor of joining the two churches by a chapel, dedicated to the Archangel Michael. This is a structure without aisles and with but one apse, covered by two domes; it is highly irregular in form to make it fit between the two churches. Parts of the walls of the churches were demolished so that all three sections opened widely into one another. John also added an outer narthex, which must once have extended in front of all three structures, but which now ends awkwardly in front of the mortuary chapel. The middle church was designed to serve as a mortuary chapel for the Comneni dynasty, beginning with the Empress Eirene, who was reburied there after its completion. Her verd antique sarcophagus was opened up and robbed by the knights of the Fourth Crusade when they sacked Constantinople in 1204. Her looted sarcophagus stood outside the Pantocrator up until the middle of the last century, when it was removed to the exonarthex of Haghia Sophia, where it is preserved today.

A programme of restoration and study of the Pantocrator has been undertaken by Professor Robert Osterhaut of the University of Pennsylvania and Professors Metin and Zeynep Ahunbey of Istanbul University. The roof and domes have been restored, while a start has been made on restoration of the interior and an archaeological study of the structure.

One of the derelict Ottoman structures behind the Pantocrator has been rebuilt and renovated by Rahmi Koç, and is now a superb restaurant-café known as the Zeyrekhane. The large terrace of the Zeyrekhane, part of which is adorned with ancient architectural fragments, commands a sweeping view of the first three hills of the old city above the Golden Horn, an ideal place to have lunch before continuing to explore the Fourth Hill.

What may perhaps be the only surviving part of the monastery of the Pantocrator stands about 150 metres to the south-west of the church. To find it we take the street which leads off from the far left-hand corner of the square and follow it to the first intersection. Following the street which leads around to the left, we come immediately to a tiny, tower-like building known locally as

Ş

eyh Süleyman Mescidi. This may possibly have been one of the buildings of the Pantocrator monastery, perhaps a library or a funerary chapel. The lower part is square on the exterior and octagonal above; within, it is altogether octagonal, with shallow niches in the cross-axes; below is a crypt. This strange building has never been seriously investigated, so that neither its date nor identity are known.

HACI HASAN MESC

İ

D

İ

Returning to the last intersection and crossing it, we continue on in the same direction along Hac

ı

Hasan Soka

ğ

ı

. At the end of this street, about 100 metres along, we see on the left a tiny mosque with a quaint and pretty minaret. The people of the district call it E

ğ

ri Minare, the Crooked Minaret, for obvious reasons. It has a stone base at the top of which is a curious rope-like moulding. The shaft is of brick and stone arranged to form a criss-cross or chequerboard design, which is most unusual, perhaps unique in Istanbul. The

ş

erefe has an elaborate stalactite corbel and a fine balustrade, partly broken; but it seems a little too big in scale for the minaret. The mosque itself is rectangular, built of squared stone and with a wooden roof; in its present condition it is without interest. The founder was the Kazasker (Judge) Hac

ı

Hasanzade Mehmet Efendi who died in 1505; the mosque therefore must belong to about this date.

THE CHURCH OF ST. SAVIOUR PANTEPOPTES

If we turn left beyond the mosque and then right at the next corner into Küçük Mektep Soka

ğ

ı

, we see a Byzantine church at the end of the street. This is Eski Imaret Camii, identified with virtual certainty as the church of St. Saviour Pantepoptes, Christ the All-Seeing. This church was founded about 1085 to 1090 by the Empress Anna Delassena, mother of the Emperor Alexius I Comnenus and founder of the illustrious Comneni dynasty which ruled so brilliantly over Byzantium in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Anna ruled as co-emperor with her son for nearly 20 years and during that time exerted a powerful influence on the affairs of the Byzantine state. In the year 1100 the Empress retired to the convent of the Pantepoptes and spent the remainder of her life in retirement there. She died in 1105 and was buried in the church which she had founded. The church was converted into a mosque almost immediately after the Conquest. For a time it served as the imaret of the nearby Fatih Camii, and thus it came to be known as Eski Imaret Camii.

The building is a quite perfect example of an eleventh-century church of the four-column type, with three apses and a double narthex, many of the doors of which retain their magnificent frames of red marble. Over the inner narthex is a gallery which opens onto the nave by a charming triple arcade on two rose-coloured marble columns. The church itself has retained most of its original characteristics, though the four columns have as usual been replaced by piers, and the windows of the central apse have been altered. The side apses, however, preserve their windows and their beautiful marble cornice. The dome too, with 12 windows between which 12 deep ribs taper out towards the crown, rests on a cornice with a meander pattern of palmettes and flowers. The exterior, though closely hemmed in by the surrounding houses, is very characteristic and charming, with its 12-sided dome and its decorative brickwork in the form of blind niches and bands of Greek-key and swastika motifs and rose-like medallions.