Sixes Wild: Manifest Destiny (2 page)

Only a fool’d come back here. And yet here I sit...

Light’s fading. Could be the iron’s clean, but I get finicky with time on my paws. Coat the brush in oil and twirl it through the works of the gun, always pushing clear through before I pull back. Wouldn’t do to ruin Blake’s fancy present.

Blake. Who names a kid Blake? Doesn’t exactly strike fear into the hearts of criminals. You can tell his parents wanted him to be a fancy lawyer type.

I give the gun another going-over with fresh flannels. Once I’m satisfied, I click the barrel back home and fix the base pin.

Smartest thing would have been never to come here. Second best would be riding out this very instant, never looking back.

Like to think I’ve got a good down-to-earth sense about me. So what in Sam Hill am I doing here? Not drowning in dinero, that’s for damn sure.

I never had this manner of trouble ‘til six months ago...

This is my way in the world.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

My paws rest on matched guns, touching the barest hint of an echo. The echoes are nothing direct, mind you, more like feelings, instincts. But I’ve gone through the mill more than once, and I’ve learned to trust ‘em. I’m faster with this iron than some poor farm bunny ought to be, which is the better part of why I’ve survived out here on the wilder edge of the world. The other part is being cautious.

Take this town for example. Whenever I decide to hit up a burg, I always like to take some time an’ study it first. Watch the here and there of it. This little stop in White Rock’ll be no different. Smallish place, maybe a hundred people, maybe two hundred. Most are the decent sort of folk, though there are hard cases aplenty. Rough sort makes all the noise and most of the money, but that’s just the nature of the Frontier.

The desert sun bakes my fur. During my little look-see, I catch glimpses of the usual fare of faded wood: general store, city office, and a pawful of saloons. Those last are the real places of business for a bunny of my skills. Pockets get a mite looser when people get drunk. To save them worries, I usually have the decency to rob a game of cards. Besides, I only steal from folk who deserve it, mostly, and it’s rare for me to find a saloon without some manner of jackass in need of his wallet being lightened.

I mosey on past the stables, eyes open for a pony I might want on the way out. I’ve been walking since my last business engagement ended with me getting a hop on before I could get to the stables. Some folk take it so hard when you steal from them.

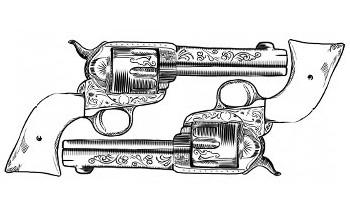

My paws caress the handles of my guns. I know every angle and groove on them, like they’re a part of me. They’re ace-high jobs, all silver and finery. Most expensive thing I ever laid paws on— my inheritance in whole and sum. Mother a’ pearl handles gleam over etched silver. Some folk get taken by the notion of relieving me of them, a notion that draws bullets. Can’t say as I blame ‘em entirely; draws the eye when they shine silver as twin moons out the top of my holsters.

I choose a saloon. Doesn’t pay to get too particular; good luck and a quick draw can get me in and out of the right sorts of trouble. Breezing in all casual, I order a beer, even though I hate the stuff. Something about the bubbles disagrees with my nose, makes it wiggle something fierce, but folk send hassle your way if ya nurse the same glass of whiskey for an hour. I settle in with my drink and let my ears do the work.

This is my way in the world; I listen. Unlike the most of hares, however, I run toward trouble instead of away. See some shave-tail get roostered and slip on his own spilled booze, then filch his pocket-watch while you help him up. Wait for some brutes to get into a brawl, then steal the purses off their belts as I shove ‘em off my table. Hell, once I even palmed the gold tips off a deer’s antlers. Cost me a bottle of Kentucky Red-Eye, but the buck kept trying to make a mash on the bardog’s daughter, so he had it coming.

Really, it’s a good life. Not an excess of comfort, true, but not an excess of rules either. If any real difficulty ever kicks up, I just shin out. Ain’t no place like the out of doors for a hare and besides, I look harmless. Just another bunny you’d pass on the road, a little tall maybe, but what’s another tall fella to the world?

Settling in casual-like, I take in the bar. Fresh sawdust on worn floorboards. The stench of rotgut whiskey and unwashed bodies soaks the air. I chance a sip of the beer— swill as expected, warm and going flat. Some folks are losing their pay at the poker table, and the saloon girl is making her rounds, conning the menfolk into buying more drinks with winks and charm. The old border collie behind the bar keeps asking the same patrons if they’d like a drink from “genuine echoed” glasses in his breathless, excitable way.

Then I hear it— whispers though the wall. I’m led back by the ears, leaning back ‘til they’re flat against the wall. I listen. In the back room, I can hear a deal brewing…

I ain’t keen on that mine.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I snarl. We lions aren’t known for our patience.

“Let’s keep this simple.” I interlace my fingers, paws on my chest, feet on the table, like Father so often did. Shows I’m at ease, in control, powerful: everything a lion ought to be. “Since tomorrow’s the Fourth, I’m going to be out enjoying the festivities. You go in, rob my store, leave with the cashbox. Got it?”

The lynx takes another gulp of whiskey. No wonder his voice grinds like grit. “I ain’t some soft-in-the-brainpan prey, Hayes. I get the plan. When do we get paid?”

To his left, two cats make a show of checking their guns, trying to look tough. To his right, a boar smokes his pipe and doesn’t have to make a show of anything.

The shorter of the two cats squirms. “Why’re we stealin’ from you? Can’t ya just give us the money right now?”

“I’m paying out a large amount of cash all at once, enough that it would be noticeable to anyone who looked over the books.” I smile. Stealing money from myself is a properly devious plan. That’s why I’m the boss: predator cunning. “Now, when Morris meets you out at the old mine, he’ll pay you half. When you finish delivering the cash to everybody on the list, you get the other half.”

Morris hands the lynx a slip of paper. That dandy rodent’s one of the few leaf-munchers I can tolerate. He’s local, and showed up around the time I inherited the mine, like he could smell the money. His wits make him damn useful —he even threw a bunch of small bills and cards around the table in case some fool walked in on our little meeting— but his constant twitching and chittering gives me the nerves. Rodents...

The lynx snatches the paper away, making the little marmot jump back and straighten the vest over his wide belly. The feline twitches his tufted ears, scouring the list over. “Blazes! There are damn judges on this list! Even the mayor down in Chance Canyon. You reckon we can just walk in and make a social call?”

I laugh. “They’re all expecting you. Just take a bath first, they’ll let you in.”

He growls, but stuffs the list in his pocket. That’s the way with him: he’ll bitch and bellow, but he gets the job done. For close on three years, he’s been one of my best and knows it. The boar is for muscle. The two scrawny cats are a fairways useless, but I know where their families live and made it clear living’s a precarious thing out here. They’re going to make sure nobody gets greedy. Best of all, none of them have been in town much and won’t be recognized by the sheriff. Simple.

The lynx leans back, copying my posture. “I ain’t keen on that mine.” Years back, a rumor just happened to spring up that the mine was cursed, which keeps folk from pointing their noses where they don’t belong.

The other three shift and look at each other, suggesting it’s a common sentiment. You’d think they believed the very rumor we spread.

I spread my wide paws, looking all reasonable. “Gentlemen, I have money. I pay you to make things happen. That’s life. If you don’t like it, find somebody else to pay you. The difference is, it won’t be as much.” I lean forward, my claws carving furrows on the table as if it were soft leather. Or their hides. “Now get to work.”

The four of them leave. Even that lynx knows he can only press me so far; the fang marks scarring his spotty throat serve to remind him.

Morris scoops the cards and cash off the table, sorting each with twitchy little paws. Once finished, he gnaws at a blunt claw.

“I tell you, varmint, the wind’s blowing my way.” I slap him on the back, knocking him forward. “In six months’ time, I’ll have all the money I want. And all the manpower to back it up.”

He steadies himself, brushing the reddish dust off his clothes. “Best we don’t get ahead a’ ourselves.”

I ignore him, smiling. “Who would’ve thought I’d dig up something better than gold?”