Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (37 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

Amid all the struggles and not helped with the eternal heat and dust of Natal,

Shaka

Zulu

dragged on and on. With our challenging scripts we felt as if the production would never end as the schedule kept slipping back with time wasted filming second-unit material. Discussing this problem with the director, I recommended my old friend Jimmy Devis as an established second-unit director/cameraman who could help with this problem; Jim would join the unit for the next six weeks to help get us back on schedule.

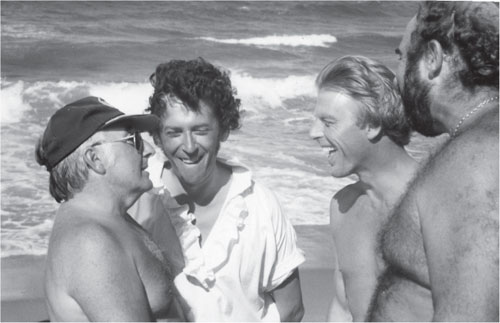

On the beach with Edward Fox, at the start of a long journey for the whites back to Cape Town.

SABC Television also became concerned with the slow progress of our filming, which, as you would expect, did not come easily with thousands of spear-carrying Zulus, all frustrated at the silly games which the whites enjoyed playing.

Fourteen long months would eventually pass before

Shaka Zulu

finally came to an end, and now it was time to bid farewell to our Zulu friends. I was grateful for the experience in understanding how the Zulus had inherited their sadistic past from Shaka, but more important to me was the technical knowledge I had gained from the challenges which I had had to solve with my own photographic struggles. I now look back on the production with much satisfaction after seeing the final result on the screen.

All good things eventually come to an end. SABC celebrated the moment with the traditional end of picture party with a wonderful atmosphere as everyone relaxed at the end of a long challenging series. With all pressure off, it was time to unwind before flying home. As Frank and I were both teetotal there was little chance we would wake up the next morning with a hangover. Our priority was to be on time at Durban airport before Bill Faure decided he needed more covering material.

Frank being Frank, with an equally greedy Alec, it was difficult to refuse the waiters’ offerings as they kept refilling our plates with their sweet delights. Coming to the end of the merrymaking, I found myself feeling very tired … slowly drifting … which was the only way I could describe my fast-changing condition. At first I put it down to over-tiredness with the heat and body relaxing. I went along with this self-delusional dream. Now with the celebrations over we walked out to my car, where the fresh air had a sudden, unexpected impact on my condition.

I vaguely remember struggling to get ‘up’ into the driver’s seat, where everything seemed distorted … unreal. My manner had changed; apparently I was rude, complaining that the car’s wheels were too big for a vehicle of this size, which was confirmed when I looked out the window to see Frank apparently looking up at me, wondering what the hell I was going on about as he climbed up next to me. Looking in the rearview mirror I noticed someone sitting in the backseat.

‘Throw him out,’ I said angrily. ‘Who the hell is he, anyway?’

By now Frank was thinking I had lost my mind, explaining that there was no one there, but to humour me he checked anyway. Satisfied all was well, I drove slowly back to my apartment, and by now the car wheels had stopped growing, although the car now seemed to be ‘floating’ above ground – a weird car, I thought to myself. Dropping Frank at his flat, I drove slowly back to my bungalow in this strange dream-like state. Once inside, feeling thirsty, I turned to the refrigerator but was unable to reach the door, even with my curiously long arms. Still none of this bothered me as I happily relaxed in this strange dreamlike state before falling into a deep sleep in the chair.

The next morning I woke feeling very fragile. I would later learn that Frank had been through a state of mind similar to the one that I had experienced, though in his case more delayed. Before starting out to the airport we shared our goodbyes with Bill Faure, who then revealed all about our condition. It would seem that the delicious cakes which we had greedily consumed were generously laced with cannabis seeds to get the party going – shades of Antonioni again? They had never considered that anyone would eat as many as we did. It would seem that our greed was responsible for our state of mind, resulting in an interesting experience one never forgets – or would want to repeat!

The launch of the boat

Chaka

(possibly Shaka’s real name), with me laying down the law! And to think I used to dislike the navy pigs!

It was time to return to our own civilisation, England, this peaceful isle. Insanity awaited our return when we learned that, due to the apartheid situation, the transmission of South African television productions was now banned in the UK.

Shaka Zulu

would be one of the casualties, so the question now was whether anyone would ever see the series here in the UK. Would the viewers be interested to learn of Shaka’s story on television, or – more importantly – would any producers see the results of my photographic efforts? Worse still, there was even a possibility that the Brits working on the film could be blacklisted by the ACTT – our own very political left-wing trade union at that time – for working in South Africa at all, but fortunately that problem would be resolved before getting tangled up in the courts.

I can’t remember what the joke was about. Knowing Frank, it was probably at my expense, but obviously Robert Powell and Edward Fox enjoyed it.

Edward Fox, Robert Powell, Trevor Howard, Fiona Fullerton, Christopher Lee, Roy Dotrice, Gordon Jackson, Kenneth Griffith and Dudu Mkhize all happily contributed their talents to the screen version of E.A. Ritter’s 1955 novel

Shaka Zulu

, where our fourteen long months of filming would hold faithfully to the detailed script, retaining the atmosphere of the period. An interesting American article of the time wrote that

Shaka Zulu

was the most repeatedly screened mini-series ever shown on syndicated television in the United States, with the series achieving cult status. By 1992 it had been seen by over 350 million viewers, dislodging John Marshall’s

The Hunters

(1962) and later

The Gods Must Be Crazy

(1981) with its follow-ups as the prime shaper of American perceptions of African tribal history.

I settled for that, though it does seem strange that, to my knowledge,

Shaka Zulu

was never broadcast here in the UK, which no doubt was inspired by the boycott. If it was shown, then I missed it. Even so, I was pleased with the American reviews – you win some, you lose some!

Fourteen long months working in a foreign country – out of sight and out of mind – had not been an easy decision to make. However, should the gamble pay off, which it did with

Shaka

receiving excellent reviews in America, then perhaps the sacrifice was worthwhile.

On my return to London I would learn that I was not the only cameraman with this problem; others before had in their frustration at the shortage of opportunities also looked abroad in order to fulfil their ambitions. I happened to be discussing this problem with Ronnie Maasz, a colleague who at the time was enjoying a successful reputation filming overseas, but that was not the life for me, and at least I could now take comfort from my three little films; with

Shaka Zulu

added to that all-important CV there could be no turning back now.

My optimism grew as my good fortune continued, my L-plates could now be removed, with Stanley O’Toole offering me his latest film with the Oscar-winning director Franklin Schaffner. It would seem that after helping Stanley to make his debut as director one good turn deserved another, but this time there would be no haggling over my salary in Stanley’s car – I now had an agent to deal with that problem.

Filming

Lionheart

near Budapest in 1986. Frank Elliott is on the crane, with Franklin Schaffner standing behind me.

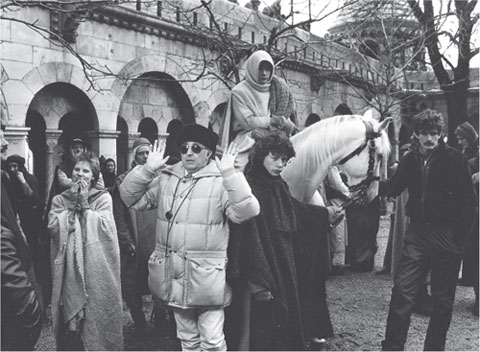

On location in Budapest at the famous Fishermen’s Bastion. The hooded figure on the horse is Eric Stoltz, the lead character in the film; holding his reins in the foreground is Dexter Fletcher and on my right is Sammi Davis.

Even so, I still had my concerns with the director’s reaction to me photographing his film. The last time we worked together I had been Franklin’s camera operator on

Sphinx

, where I suffered a week of filming before he decided whether or not he could trust me. However, my reservations were dispelled by the director’s generous support towards me; apparently Franklin had also enjoyed the

Shaka

series in America.