Rough Ride (19 page)

Authors: Paul Kimmage

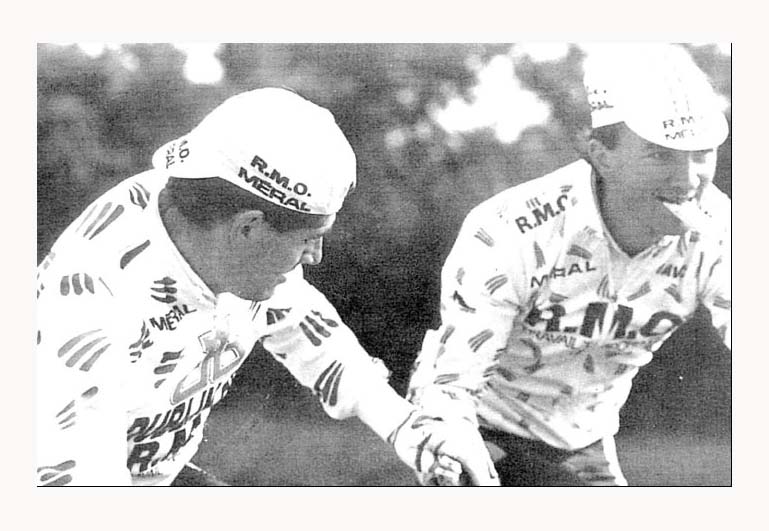

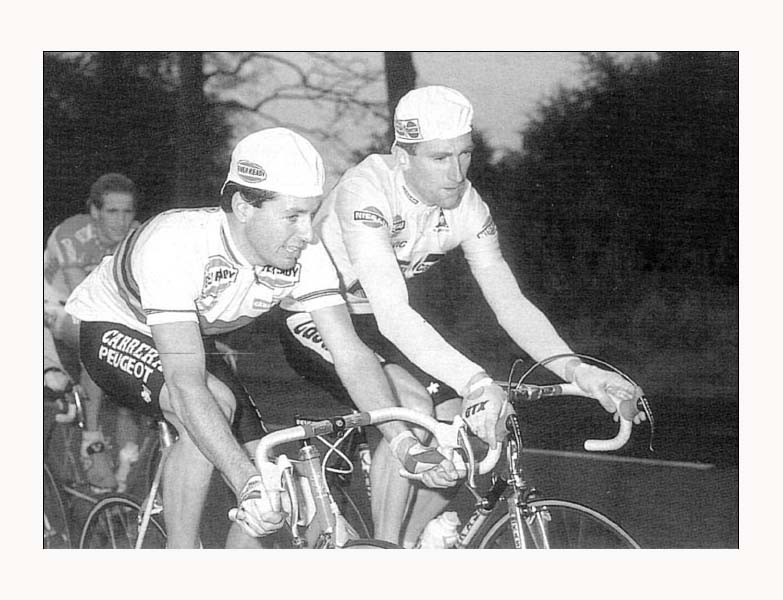

Claveyrolat shares his supply of food – Nissan '87

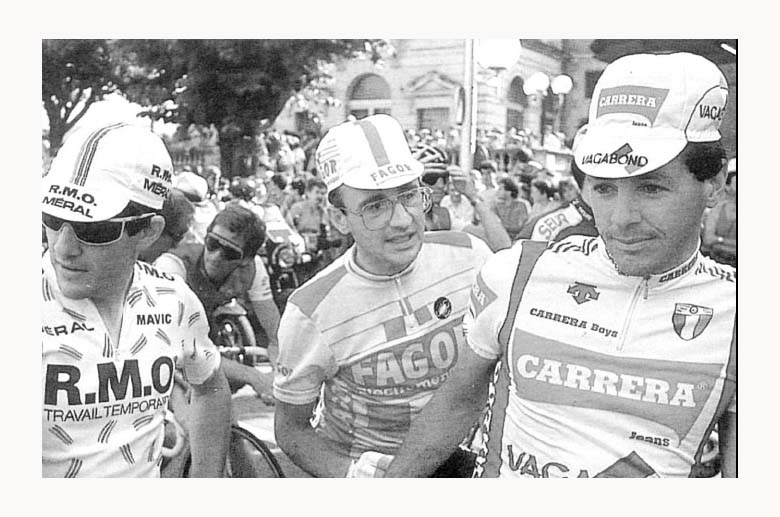

Smiles before the miles: riding out with Stephen and Martin Earley in the '87 Tour

Shades, suntan: I'm looking pretty cool this morning with Martin and Stephen at Orleans – '87 Tour

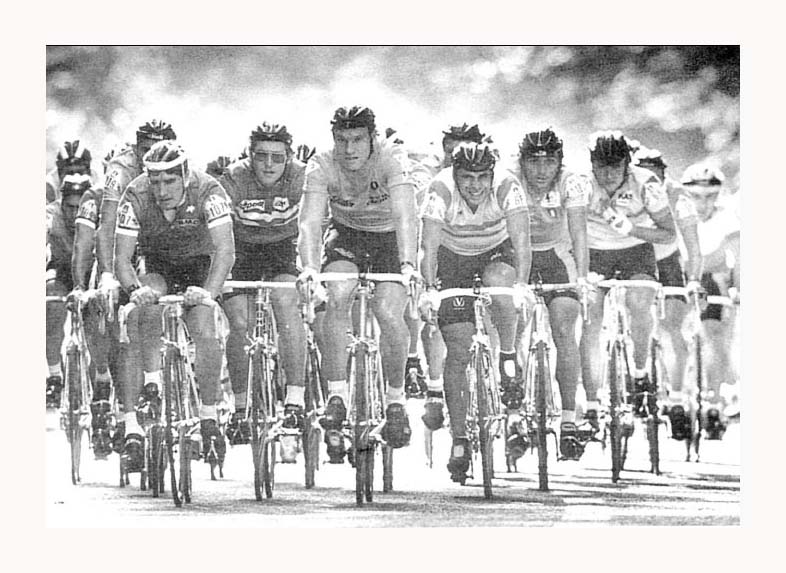

World Road Race Championships, Belgium 1988.

The rider in dark glasses, to my left, is Jorgen Pedersen.

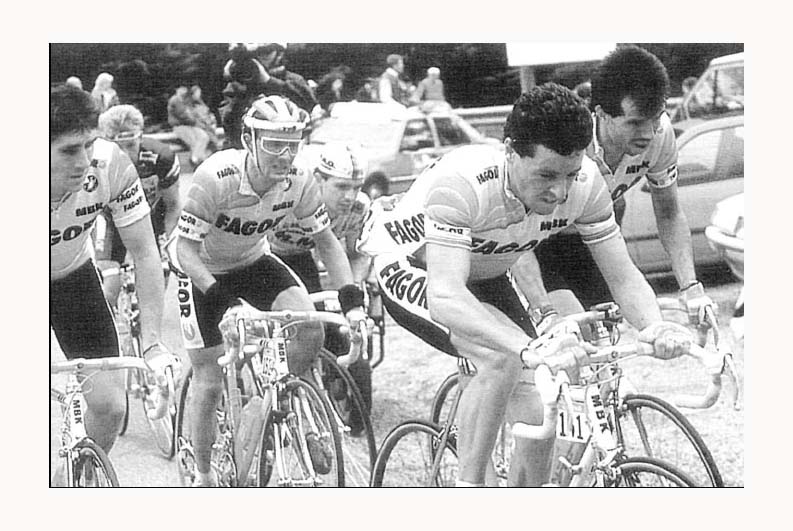

And now the end is near: the Aubisque mountain, '89 Tour –

Stephen's last day on the race. The Fagor riders

(from left to right):

Kimmage, Biondi, Roche, Lavenu and Schepers (his back)

The heroes: without Roche and Kelly I would never have

survived my four years in the professional peloton

Tour de France '89. Montpellier, 13 July.

The evening of my last race as a professional. Hours earlier I

had abandoned the Tour and my career as a pro cyclist

Hillwalking with Ann in the Alps, August '89

I was disappointed, but had expected it. The day after the Armorique we stayed in Brittany for the Grand Prix of Plumelec. A single-day race, Plumelec is one of a series of French classics where there are never any controls. These races are know among the pros as the Grands Prix des Chaudières.

Chaud

means warm. The word

chaudière

is used for someone who heats, who warms up, who takes a charge. Mauleon-Moulin, Châteauroux-Limoges, the Grand Prix Plumelec, the Grand Prix of Plouay, the Grand Prix of Cannes – all are Grands Prix des Chaudières. At the team meetings on the night before these classics the dialogue from the

directeur sportif

was always the same. 'Now lads, I can't say there won't be a control tomorrow but this is Plumelec'

And there would be spontaneous laughter.

'We are all professionals, so it's up to each of us to conduct ourselves as such. If there is a surprise control and anyone is caught, I will do my best to protect you as far as the sponsor is concerned.'

I could never bring myself to charge up for the Chaudières races and always went into them with an inferiority complex. As a result of not taking anything I felt disadvantaged and never bothered even to try to win. It was those high principles of mine: there was no way I could be happy winning a race, knowing I had charged for it. And yet I am forced to admit that a lot of it was purely psychological. In my first year I was as green as grass starting the Grand Prix of Plumelec. I didn't realise it was a Chaudières. I felt I was riding on the same level as everyone else, so it didn't bother me. I finished eighth. But three years later I was a man of the world. I knew what was going on but wasn't mentally strong enough to still try and win.

Plumelec is a five and a half hour race. It was a foul day, raining and miserable. Tired from the Armorique stage race, I was never going well. Half-way through, on one of the small back roads of the circuit, we were strung out in one long line. I was second to last and Dede last. I knew he was getting it rough so I looked around to see how he was. His body and face were wet and mucky from the spray from the back wheels. He had something between his teeth – a needle. He bit the plastic cap off and I immediately understood what he was going to do next. I dropped behind him to push him as he injected himself with the white liquid, most probably amphetamine. This was to help him to get it over as quickly as possible so no one would see him.

To see him dirty, suffering and with that needle between his teeth turned my stomach. I wanted to get off and just leave the bike there and then. I abandoned the race and rode straight to the showers. I was disgusted. Not at Dede, he was simply playing by their rules, another innocent victim. No, I blamed the system. The race organisers, the

directeurs sportifs, th

e sponsors – the men in power who knew what was going on but turned a blind eye to it. And when his career ended the system would spit him out – a penniless ex-pro. The incident strengthened my conviction never to enter the drugs stadium. I would go as far as I could for as long as possible, but if it wasn't good enough then it was just too bad. If someone had offered me a decent job that Sunday in Plumelec I'd have taken it, there and then. But I had to keep trying. There were bills to be paid, responsibilities to be met – and a little flicker of hope about riding the Tour.

I believed right up until the last minute that I could still make the Tour team. It became almost an obsession. I used to take out this team poster and with a pen place crosses on the heads of those I felt had blown it. The heads of the fellows still in with a chance were marked with a question. With two weeks to go there were eight ticks on the poster. I was one of three question marks fighting for the last place. The other two were Frank Pineau and the German Hartmut Bolts.

The Midi Libre stage race was my last chance to prove myself. I worked like a Trojan for the others for the week and finished it off with third place on the final stage – a mountain stage. I was sure I had done enough. The decision was Vallet's. He said he'd make up his mind after the national championships a week before the start of the Tour. All the European and Scandinavian countries hold their professional championships on the same date. Ireland does not hold a professional championship as we are only a handful of pros. I spent the day at home, hoping against hope that neither Pineau nor Bolts would ride well. Pineau didn't. Bolts became the professional champion of Germany. On Monday I drove to a meeting with Vallet to hear the decision. I don't know why I bothered. In the morning's

L'Equipe,

Vallet had lavished glowing praise on the new German champion. I should have read between the lines and realised that I hadn't made it. But I wanted the waiting to end. I wanted to be told. And I was.

It was to be a month's holiday at the Cafe de la Gare.

Vallet told me to have a short break and to prepare myself for a good end of season. I was shattered. I cried on my way back to Vizille and the depth of my disappointment surprised me. I phoned the news home to my parents and also to David Walsh at the

Sunday Tribune.

We had planned to write a book on the Tour together, a 'from the saddle' account of the three-week race; but with my non-selection the project went out the window. David asked me if I'd consider writing a short column for the

Tribune

on the four Sundays of the Tour. I had been writing on and off for

Irish Cycling Review

for two years, but had never written for a newspaper before. David was taking a bit of a chance in getting me to write the column and stressed that I keep it short, about 500 words. If it was rubbish, then it would be just 500 words of rubbish and no one would notice too much. It was still a big responsibility, and on the morning I wrote the piece I regretted ever having agreed. I was unbearable. I ordered Ann out of the house and the slightest noise drove me nuts. But writing it was only half the battle. I then had to read the piece over the phone to a copy-taker at the paper. Evelyn Bracken was very patient and understanding but even then I hated it. I kept waiting for her to say, 'Now, hold on a minute, son, this is rubbish.' But she never did and my pieces got a good response. The first one was about being left out of the Tour. The second week I wrote about my hopes for Kelly doing well. And on the third week I did a piece which the

Sunday Tribune

entitled 'A picnicker's view of the Alpe d'Huez':

Alpe d'Huez. Thirteen kilometres of strength-sapping ascensions. Twenty-one hairpin bends that climb to almost 6,000 feet. The blue riband of the Tour, a monument to its glorious history.

Driving up the Romanche Valley, or the Valley of the Dead as it is better known, I was filled with remorse. For this morning I was going to that famous battleground, not as rider but as spectator. My wife Ann and I set out at nine, convinced that the thirty-two kilometres from our house to the foot of the Alpe would take no more than an hour to drive. I had forgotten it was Bastille Day.

All of France was on holiday and we found ourselves stuck in a traffic jam fifteen kilometres from Bourg d'Oisans, the town at the bottom of the climb. For twenty-five minutes we sat there without budging. Word came filtering back that the Gendarmes had closed the road early because of the huge volume of traffic.

We abandoned the car and walked the four kilometres to the police roadblock. It was too far to walk to the Alpe so we set up camp on a boring 300-metre flat stretch of road, a kilometre from the town of Rochatailee.

Sitting by the side of the road I soon realised that as a tour spectator I was a bit of a greenhorn. We had no fold-up chairs to sit on. No white cotton caps to keep the sun off our heads and no transistor to keep us informed on how the race was going.

We did however remember the picnic basket. It soon became evident to me that many other people had lost hope of getting to the Alpe, as little by little our anonymous piece of road started to fill with picnicking families.

The hours passed slowly and I found myself becoming more and more frustrated at the lack of race information. I spotted a veteran Tour spectator across the road. He had the vital equipment and I decided to ask him if he had heard anything. He told me that Fignon had not started the stage and that Jean-François Bernard had lost contact on the Col de la Madeleine and was trailing the leaders by five minutes.

I was amazed. Bernard had been my Tour favourite. The old spectator had no news of Kelly. I went back to Ann and we began eating lunch. I dropped my baguette when the old man raised his arm to me. Kelly was four minutes down.

Merde!

I was really disappointed.

Kelly had lost the Tour, for I knew that those four minutes would soon double and maybe even triple for they had not yet crossed the Glandon and there was still the Alpe to come. I thanked the old man for the last time. I had no more interest in crossing the road.

The publicity caravan arrived. I recognised the co-

directeur sportif

that I had had in 1986, Jean-Claude Valaeys. He was throwing plastic bags and paper hats out of the window of his brightly coloured Peugeot. Never liked the guy.

The roadside nicely littered, we waited for the main act. Rooks and Delgado duly obliged and for fifteen seconds we watched as the two heroes battled their way up the road, dwarfed by the swarm of TV cameras and photographers and race organisation vehicles. Group after group the shattered faces rolled by.

I shouted encouragement at Claveyrolat and Colotti, the two team-mates I regarded as friends. But as my other team-mates passed I held my breath in disrespectful silence.

Another group appeared. Three yellow and blue jerseys riding at the front. I knew immediately this was the Kelly group. I looked at my watch. Fifteen minutes had ticked past since Delgado and Rooks had gone by. Martin Earley was riding at the front of the group. I was pleased, for it was his place. It is ungraceful and unjust that the giants of the road be left isolated on the days they are ordinary men.

Sean was in the middle of the group. In our best Irish accents we shouted at the two of them but they did not look up.

Ann had seen what she had come to see and she started the long walk back to the car. Strangely, I found myself not wanting to leave. Two years previously I had ridden along this very stretch of road on this very same stage of the race. I was thirty-five minutes down and alone.

I can remember the encouragement that I received from those spectators who had waited. I felt duty bound to wait a while. If I had been riding I would have been in one of these groups. On a good day I might have been with the Kelly group. A bad day and I would have been in one of the groups that were now passing before my eyes, forty-two minutes down.

I watched in silent homage. Still no sign of the last rider. I decided I would have to go as Ann would be waiting for me and I thought I felt a drop of rain. I felt guilty. I should not have left. The cock crowed three times as I walked back to my car.

I liked the Alpe piece. I was starting to relax a bit more and was even managing to sleep a little on the night before writing an article. But a day after the Alpe stage something happened that put an abrupt end to my series of articles on the race. The race leader Pedro Delgado was found positive at dope control.