Restitution (6 page)

“There may be an advantage for us in all of this,” said Karl, as the students began to enter the building. “As long as Czechs are focused on Germans, either here or in Germany, perhaps they'll be less likely to focus on us.”

“I doubt it,” replied George. “I suspect that Jewish families living in the north are going to be flooding into this part of the country. Why would Jews want to stay there knowing how much Hitler hates them â hates us? And if you think Jews are going to be welcomed here, then you're totally naive. I can't wait to get out of here,” he added, “to get to Prague where at least it doesn't feel as if everyone knows you and is watching you. I just wish my family were coming with me. You need to get out, too.”

Within the Reiser household, Leila was particularly distraught over the news of the annexation of Sudetenland. It was difficult for her to understand the bitter fragmentation of her country. Her roots were in Sudetenland, where she had been born and where she still had relatives. And yet, her heart was here with the family she had been with for almost two decades.

Later that day, Karl walked home with Leila after accompanying her to the market to pick up some groceries.

“What would I do without your family?” Leila muttered as she struggled to keep up with Karl's long stride. “Yours is the only home I know.”

Karl squeezed Leila's arm reassuringly. He glanced around to make sure no one was listening. Leila's Czech was extremely limited, and German was the only language she spoke in the Reiser home. But here in public, Karl was cautious about responding. These days, speaking German was probably as dangerous as acknowledging one's Judaism. He did not want to provoke anti-German sentiments any more than he wanted to incite anti-Semitic ones, and both were easily aroused. He nodded, and ushered Leila along. It was only once they were safely back home and Karl had deposited the groceries in the kitchen that he turned to face her.

“You're the mainstay of this family, Leila,” he said in his near-fluent German. “We'd be lost without you.” He hugged her lovingly, nearly smothering the tiny woman.

“And you and Hana are like my own.” Leila returned the hug, sniffling loudly, and then shooed Karl out of the way so that she could begin to prepare that evening's meal.

But the news of the Sudeten takeover was still troubling Karl. He was overwhelmed by the growing fear that his mother and George Popper might be right, that this was only the beginning. There was a smell of war in the air, and it was settling over the country like a thick fog. It had been easy to dismiss the unrest when the events were taking place elsewhere, across the borders. Karl, like many others, had tried to hold fast to the belief that his country was safe from conflict and that if circumstances escalated, other countries â more powerful and influential â would come to Czechoslovakia's aid. One by one, these beliefs were being eroded.

And the situation continued to spiral downward. That November, in Germany and Austria, Jewish shops and department stores had their windows smashed and contents destroyed in what was being called

Kristallnacht

â the night of broken glass. One hundred and nineteen synagogues had been set afire and another seventy-six burned down completely while local fire departments stood by. More than two hundred thousand Jews had been arrested. Many were beaten and even killed. Once again, Hitler's voice shrieked from the radio. Appearing before the Nazi parliament, Hitler made a speech commemorating the sixth anniversary of his coming to power. He publicly threatened Jews, declaring, “In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and have usually been ridiculed for itâ¦. Today I will once more be a prophet: if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the bolshevizing of the earth and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!”

4

That same month, Karl celebrated his seventeenth birthday. What should have been a memorable occasion passed as a non-event in the Reiser household. There was no possibility of festivities given the intense feelings that

Kristallnacht

had aroused in everyone in the family. As Marie became even more resolute in her urging to leave the country, Karl felt his resolve crumble once and for all. He joined his mother's camp, advocating for the family's immediate departure from their home. Meanwhile, Victor continued to pronounce that all was still well.

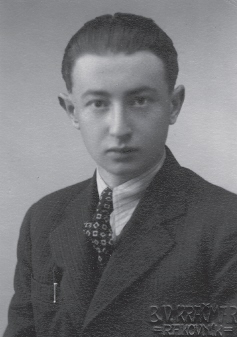

Karl at age 16 in Rakovnik

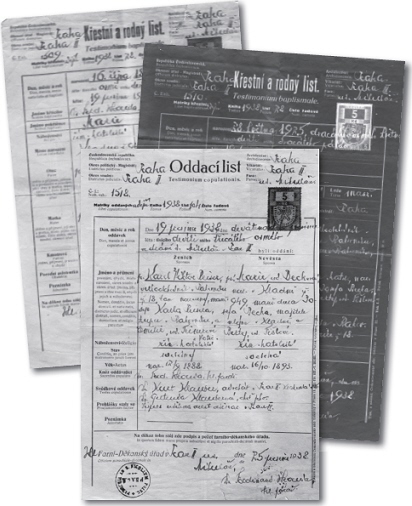

Marie and Victor's Catholic marriage certificate, dated December 19, 1938. Behind are Marie and Hana's false baptism certificates.

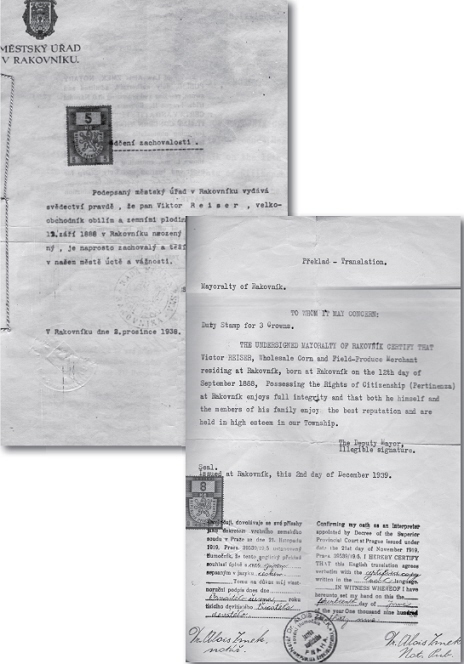

A letter from the Deputy Mayor of Rakovnik (top) dated December 2, 1938, stating that the Reiser family is held in high esteem within the community. The translation (bottom) is notarized in Prague on June 14, 1939, suggesting that Marie must have had the translation done when the family fled there.

RakovnÃk, Late 1938

BY LATE 1938, despite the fears arising from

Kristallnacht

, life went on as usual in RakovnÃk. There were still no laws enacted to discriminate against Jews in Czechoslovakia. Victor's work continued unchanged. The family lived in their home and could come and go as they wished. The synagogue was open and functioning. Karl still went to the theater and cinema, played sports, and socialized with his few friends. School exams were still approaching.

Victor noted the passing of time with satisfaction. “You see,” he said. “I told you things would be fine here.”

And while Marie shook her head in response, pursing her lips in a grim line, it was true that, while war and the loss of freedom threatened at Czechoslovakia's doorstep, that door had so far remained shut.

One day in February 1939, Karl arrived home to some unfamiliar voices coming from the sitting room. He closed the front door behind him and removed his jacket, which was still wet from the rain and snow falling outside. Shivering, he walked toward the noise in the salon. It was difficult to keep the house warm even for a family with enough money to heat the wood stoves and fireplaces.

“Ah, Karl,” his mother said as he stood in the archway of the salon. “Come in.”

Karl entered and greeted his parents. There was another man in the living room, someone Karl didn't know, and he waited expectantly.

“This is Mr. Schmahl. He owns an art gallery in the next town,” Mother announced. “Our son, Karl.”

Karl reached out to shake hands with the stranger. He was in his thirties, a dumpling of a man, dressed in a well-tailored, dark silk suit. He shook hands with Karl and bowed formally. Karl noted the large gold ring on his finger. A second stranger, similarly dressed, hovered in the back of the sitting room. No one moved to introduce him.

“Mr. Schmahl married our cousin, Irene,” his father said. Karl glanced at his father, surprised by the disdainful tone in his voice. His dislike for this gentleman was obvious, and this puzzled Karl. Mr. Schmahl was talking and Karl stepped to one side of the room to listen in on the conversation.

“As I was saying, my business has not gone as I would have hoped. People simply do not appreciate fine art anymore. All this talk of war has scared many off from purchasing art. Besides, who would have suspected a Nazi occupation when we opened our gallery in Karlovy Vary? Certainly not us.” Karlovy Vary was located in the Sudeten region. “I have been forced to close my gallery, despite my best efforts.” Mr. Schmahl shook his head and tugged nervously at his tie.

“Perhaps your extravagant lifestyle has something to do with the failure of your business,” Victor commented curtly. This set Mr. Schmahl on another round of tugging and twitching.

“Not at all,” he stammered. “In the art business, one must look the part if one is to succeed.”

Karl was beginning to understand his father's reaction to Mr. Schmahl. Despite their family's wealth, Victor was a modest man. He was unassuming and reserved when it came to outward shows of prosperity. In contrast, Schmahl flaunted his wealth, from his gold cufflinks, silk tie, and fine leather shoes to his affected speech. Even Karl knew that parading one's wealth was not recommended in a country that needed little provocation to target Jews.

Mr. Schmahl struggled to compose himself. He hesitated, then stumbled on. “At any rate, the loan which you so graciously gave me â I'mâ¦I'm afraid that I will have trouble paying it back.”

Victor said nothing. It appeared that this news did not surprise him. Marie stood next to her husband, silently watching the exchange.

“But I am an honest man, I assure you. And I honor my debts. I've simply fallen on hard times,” lamented Mr. Schmahl, “like so many others these days. Surely you as an astute business man will understand this.” By now, he was practically convulsing in front of Victor, who continued to stare in silence. “In this case,” continued Mr. Schmahl, trying to compose himself, “in lieu of the money, I have brought you these.”

With that, he gestured behind him to a tall mound, draped in heavy cloth. He snapped his fingers at the other man in the room who rushed forward to help. Ceremoniously, the two men grabbed either end of the cloth and pulled it downward, revealing a stack of paintings. With the help of his assistant, Mr. Schmahl lined the paintings up across the salon for everyone to see. They were heavy, even for two men. Karl and his parents leaned forward to inspect the artwork.

There were four canvases â large, wall-sized oil paintings, mounted in ornately sculpted gold frames. The first and perhaps most imposing of the paintings was entitled

Forest Fire

.

“You may be interested to know that this is nothing like the artist's other works,” Schmahl said. Karl squinted to see the artist's name: Rudolf Swoboda. “The painter was a well-known Orientalist,” Schmahl continued. “In 1886, Queen Victoria commissioned him to paint a portrait of a group of Indian artisans who had come to Windsor to celebrate her Golden Jubilee. She was so impressed with his work that she paid his way to India so that he could produce more paintings of her subjects. Many of his paintings of the âordinary people of India' are hung in what was once Queen Victoria's residence, Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.”

Karl looked closely at the canvas. He had taken enough photographs of the countryside around his home to appreciate the artistic details of the painting in front of him. It depicted a darkly lit forest engulfed in deep red and orange flames, creeping upward and choking the life out of the forest trees. The gray smoke appeared to almost lift off the oil; the foliage all but disappeared behind the advancing fire. Karl was mesmerized by how lifelike the fire appeared.

Mr. Schmahl was talking again. “Take a look at these two vertical paintings,” he said. “This one is called

Die Hausfrau

.” Karl glanced over at the artist's signature: Hugo Vogel, a German name. This painting was of a young woman standing in front of a draped harpsichord, her head tilted slightly to one side, absently flipping through pages of sheet music with one hand. Her other hand held a feather duster and rested carelessly on her hip. Light poured in from the window beside her, illuminating her face and the music in front of her.