Poe (16 page)

Authors: J. Lincoln Fenn

Amelia gives me the rest of the house tour while Lisa heads out to the barn to retrieve her mother. (She loses track of time, Lisa tells me, and can paint all night if no one reminds her to eat.)

“This is the kitchen,” says Amelia, dragging me by the hand. It’s small but functional, with beige painted cabinets, a scratched yellow linoleum floor, and a matching seventies olive-colored stove and refrigerator.

“I did these,” says Amelia proudly, pointing to some watercolors attached to the fridge with magnets.

“They’re great,” I say.

“Not as good as Nana’s,” says Amelia, “but she says I have potential if I can develop my point of view.”

Before I can comment on

that

I find myself being dragged through a tiny dining room. There’s barely any space between the chairs and the wall, but Amelia squeezes through easily, and I catch a glimpse of more abstract owl art, smaller square canvases this time. There’s a black owl with demonic bat wings in one, standing in an empty field that’s eerily similar to the one behind the house. A figure huddles behind a thresher: a young woman.

“

My

room is upstairs,” says Amelia, pulling my arm so hard I’m afraid it will come loose from its socket. The stairs creak as we go up. The green wall-to-wall carpeting continues, but here the walls are covered with different panels of mismatched wallpaper, stripes on one, faded flowers on another. Amelia pulls me into the first small room on the right; it’s painted bright pink, and the walls are covered with art and sheet music. A guitar sits on her small white bed, and a few lone dolls are scattered on the floor, looking neglected.

“You can get into the attic from my closet,” she says proudly, as if that were the best feature.

Next I’m pulled into a slightly larger room, painted a plain white. It has a queen-sized bed in a Shaker-style bed frame, and the sparse accessories are neatly arranged. There’s a Japanese vase containing dried milkweed pods on the simple dresser, a wooden rocking chair on a braided rug, and a carved and painted wooden owl sculpture sitting on a rustic bookshelf, continuing the theme of owls from the canvases. A third, smaller room seems to be primarily used for storage; there are sagging cardboard boxes, an assortment of plastic Christmas trees and garlands, and a sewing machine in the corner that doesn’t look like it’s been used in the past decade.

“And this is my

dad’s

room,” says Amelia. The door to this room, unlike the others, is closed.

“Um, I don’t know if we want to disturb your dad,” I say.

Amelia sighs and rolls her eyes. “He’s not

here

,” she says, as if my ignorance is astounding.

She opens the door. A small rush of stale air escapes. I peer in past the doorway. The walls are painted black. The ceiling is painted black. The carpeting has been torn up and the wooden floors are painted black. Even the windows are painted black. It’s like a dark cancerous cell, and I get a lightheaded, dizzy feeling just looking at it, like I’m back in the watery abyss at the bottom of the Aspinwall well. The closet doors are mirrored, reflecting the light from the hallway and Amelia’s small and fragile image. A mattress, stripped of bedding, has been pushed up against one wall. There is a four-pronged candelabra on the floor, and here, oddly, are the only colors in the room: the melted candles are blue, white, yellow, and black.

“Uh, is your dad coming back anytime soon?” I’m hoping the answer is never.

But if Amelia hears me, she ignores the question completely. “You want to see something cool?”

Before I can answer she’s pulled me into the room, and then she shuts the door behind us, which is painted black as well. Instantly it’s pitch black and claustrophobic. I hold my hand in front of my face and can’t see it.

“Maybe we should go see what Lisa’s up to,” I say, trying to hide the obvious panic in my voice.

“Watch,” she says breathlessly. I hear the click of a light switch.

A black light flickers on overhead, casting us both in a purplish glow.

“Look,” says Amelia, pointing to the walls.

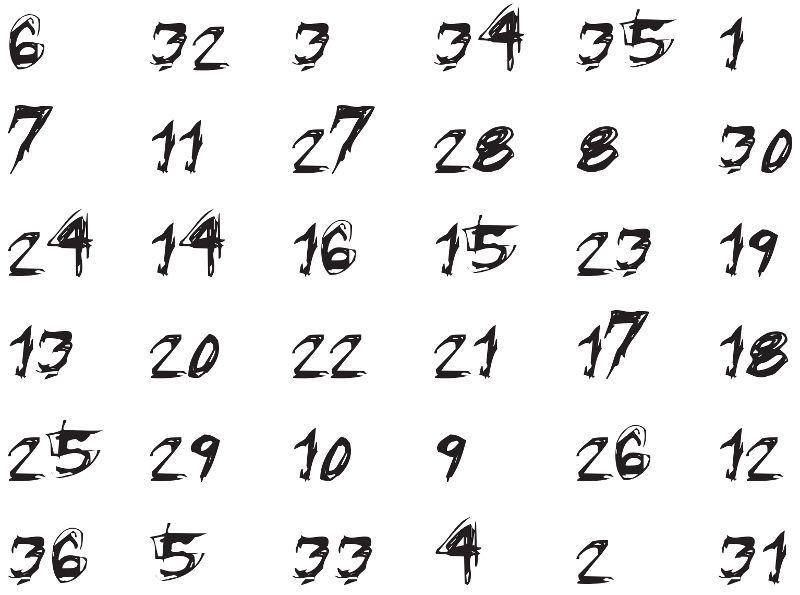

The walls are literally covered with glowing tables and numbers scrawled with a yellow highlighter, so that they can only be seen with the door shut and the black lamp on. There is something strangely

logical in its obvious madness; the same square of numbers is repeated over and over.

“He’s getting better,” says Amelia in a tiny voice. This is as much of a question as a statement.

“I’m sure he is,” I say, giving her hand a squeeze. “I’m sure he is.”

CHAPTER TEN: DEVIL IN THE CORNFIELD

D

inner proves to be a simple affair—frozen pizza, frozen peas, with vanilla ice cream for dessert. It’s nicely familiar and yet also strange to be eating at a table with people, a family. I’ve gotten used to eating fast food alone, watching the evening news—my mother would be horrified. The dishwasher hums, the microwave beeps, chairs scrape on the floor, and I feel like an outsider as everyone else maneuvers through their evening ritual—“Amelia, did you put the butter on the table?” “Anyone seen the salt?” “Who drank the last of the milk?” It’s all words to a language I’d forgotten.

Lisa’s mom, Elizabeth, seemed to stare right through me during our introduction, until Lisa said I was her friend the

writer

.

“I’m trying to find my point of view,” I said, winking at Amelia.

Elizabeth sighed, gripped my arm. “I didn’t find mine until I was forty. Don’t give up.”

We eat off paper plates, and Elizabeth and I surreptitiously examine each other while pretending not to. Elizabeth must be fifty but looks forty, with long dark gray hair pulled back in a braid. There are smudges of blue paint under her fingernails, a few spatters of yellow on her cheek, and she wears an oversized man’s white shirt over a pair of simple jeans.

“So, Dimitri, what do you write?”

“Obituaries,” I say, reaching for the salt. “And I’m working on a novel. But I’m thinking about tossing it.”

Her inquisitive gray eyebrows arch at this news. “Why?”

“It’s shit,” I say.

“Well,” she says, as she rises from the table, “you should have someone read it before you throw it away. Stephen King threw

Carrie

in the trash. It was his wife who pulled it out. Of course, she never gets any credit. The woman

never

does.”

“Typical,” mutters Lisa.

“Everyone who reads my book says it’s shit,” I say cheerfully.

Amelia bends over to Lisa. “Does he have a record deal with a major label?” she whispers.

“And do you agree with them?” Elizabeth looks genuinely interested.

I shrug. “I can’t tell the difference anymore.”

“No, sweetheart,” says Lisa, answering Amelia’s question. “He doesn’t.”

“Then how come

he

gets to use bad words?”

“I wish you’d stop telling her that,” mutters Elizabeth. “Amelia’s going to be an

artist

like her

grandmother

, not a musician.”

“I’m a writer,” I say seriously to Amelia. “Writers can use all the words they want to. It’s our job.”

“Lucky,” says Amelia, kicking at her chair.

“Maybe she’ll be a writer,” I say, and at this both Lisa and Elizabeth gasp in protest. The identical look of shock on their faces is almost comical.

“For a couple of postmodern feminists, you two are pretty controlling.”

“Ha!” says Amelia, giving me a fist bump. She’s starting to grow on me. “I showed him Daniel’s numbers,” she adds congenially.

The room drops into instant and immediate frozen silence. Lisa gives me a nervous glance and reaches for her water; her hand trembles ever so slightly.

Elizabeth sits back in her chair with a tub of ice cream and four paper bowls. She turns to me, her intense green eyes penetrating and serious. “And what did you think of Daniel’s numbers?”

I have a feeling this is a pass/fail question by the way that Lisa is suddenly gripping her fork and staring at the table. And I have a feeling I can’t pass a lie by Elizabeth.

“He’s either crazy or he’s a genius. Or both.”

“Yes,” confirms Elizabeth in a small voice. She scoops the ice cream into the bowls and then passes them around. Lisa relaxes, just a bit. “Madness and art,” says Elizabeth quietly, “are the Bennet family legacy. On the male side of the family, that is. The women, we just get the art.”

“Do they mean anything?”

“The numbers?” Elizabeth pauses, and we can all tell that Amelia is listening intently for the answer. “You did a good job eating all your peas, sweetheart. If you want to take your ice cream and go watch TV for a bit, you can.”

“I want to stay

heeerrre

,” Amelia whines.

“Go,” says Lisa firmly. “TV.”

If Amelia was allowed to swear, I’m sure we’d be recipients of a blue streak, but instead she just grinds her chair against the floor, grabs her bowl, and stalks from the room with dramatic stomps that shake the dishes in the cabinet. Immediately there’s the buzz of high-pitched voices and the usual cartoon violence from the living room.

Lisa starts to stand. “She knows she’s not supposed to watch cartoons.”

“Let her be seven for a minute.” Elizabeth waves her back into her seat. “You haven’t told him

anything

.” The accusation in her voice isn’t hard to miss.

“We’re still getting to know each other,” says Lisa defensively.

“Go get the painting.”

“Mom—”

“If he hasn’t run away screaming after seeing Daniel’s numbers, I don’t think he’s going to when he knows the whole story.”

Lisa doesn’t seem quite so convinced. She stares at her mother; an unspoken but obviously old argument hangs between them.

“Fine,” she says tersely as she stands and goes to the dining room. I can hear her lifting one of the canvases off the wall.

“More ice cream?” says Elizabeth. She doesn’t wait for me to answer and adds another scoop to my bowl anyway.

I’m starting to see why Lisa is jealous of my crappy yet private apartment.

“He was twenty-five when the voices started.” Elizabeth takes the canvas from Lisa and lays it down in the middle of the table. I recognize it from my house tour with Amelia, the demon in the field with a woman hiding behind the thresher.

“Look closely,” says Elizabeth.

Lisa sits, pulls her chair close to mine. It’s hard not to notice that she smells like Ivory soap and something else, lemony and fresh. But I look down at the painting.

The demon has the face of an owl. In fact it almost looks like the owl is wearing a black demon suit, which is binding its arms in a straightjacket.

“The owl is the guardian of the underworld; he’s the keeper of the spirits. I gave birth to Daniel in this house, and that morning an owl landed on the branch of that birch tree out there. So I started painting them. I liked them. They felt protective somehow. Like they were watching over us. Especially when their dad left.”

She sadly traces the painting on the table with her finger, a distant look in her eyes. “But this one is Daniel, after he was diagnosed.”

“Schizophrenia,” says Lisa.

“So they

say

,” says Elizabeth. I feel like Lisa wants to add something, but she doesn’t.

“He’d been trying to raise Amelia on his own, working as a mechanic during the day, playing his music at night. Sarah, his girlfriend, wasn’t ready to be a mother; she wanted to give Amelia up for adoption.

But Daniel wouldn’t hear of it. He hated his dad and felt like giving up Amelia would be abandoning her, something his dad would do, had done. So he moved back here with me, and I took care of Amelia while he was at work or traveling to his gigs across the state.”

“You probably didn’t tell him about getting into the Thornton School of Music either,” states her mother in a flat voice. I notice that Lisa is very, very still. “A very prestigious school in Los Angeles. They even offered her a full scholarship. Daniel was jealous.”

“That has

nothing

to do with anything,” says Lisa.

“He

was

,” insists Elizabeth. “He changed. You can’t deny that he changed. He painted the room black.”