Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (25 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

A more recent calamity on the Delaware River occurred on July 7, 2010, when a disabled Ride the Ducks sightseeing boat was run over by a sludge barge pushed by a tugboat with an inattentive crew. About forty tourists went into the river when the amphibious vehicle sank. Many of these people, including two who died, were Hungarians visiting the United States as part of a missionary exchange program.

First responders included men and equipment from the Coast Guard Station at Washington Avenue. The accident's location was at the foot of Chestnut Street, a stone's throw from the Great Plaza at Penn's Landing and at a spot once occupied by Smith's Island. The Georgia-based Ducks company had operated on the Delaware without incident since 2003.

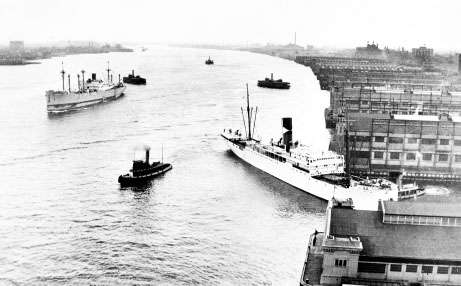

The Delaware has always been a working river, as this early to mid-twentieth-century photo indicates. Piers 3 and 5 North are at the center of a line of a dozen or so finger piers. Penn's Landing was later built in place of most of these piers.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

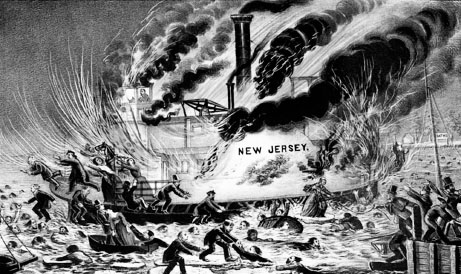

Another exciting print: “Terrible Conflagration and Destruction of the Steam-Boat ferry

New Jersey.” The Library Company of Philadelphia

.

Both of these tragedies underscore the growing tension between various activities on the river. The Delaware is a working waterway. Its use as such has diminished since the 1950s, but there's no question that sizable ships and barges still ply the waterway daily. On the other hand, its use for recreational purposes has grown dramatically in recent times, with a huge increase of sailboats, speedboats, jet skis and tourist crafts since the 1980s, as well as dockside clubs and the like.

Then again, any activity on the water is inherently dangerous. Take, for instance, the disaster of March 15, 1856, when the steam ferry

New Jersey

caught fire in the middle of the ice-filled Delaware. Operated by the Philadelphia and Camden Ferry Company, the ferryboat was carrying almost one hundred passengers, mostly New Jerseyans. It left the Walnut Street Wharf at 8:00 p.m. and was headed for Camden via the canal between Smith's and Windmill Islands.

Approaching the canal, the boat's smokestack was discovered to be on fire. The captain turned the boat around and steamed north with the tide toward the Arch Street Wharf. But before the

New Jersey

could be made fast, the engine room and pilothouse burst into flames. Now without power and out of control, the ferry was pushed by ice floes to the middle of the river. Passengers tried to save themselves by jumping onto icebergs or into the frigid water. The

New Jersey

finally went under just off the Camden shore. Sixty-one men and women drowned or burned to death on the icy Delaware.

T

HE

R

ESIDENCES AT

D

OCKSIDE AND

W

ATERFRONT

S

QUARE

Immediately north of Pier 34 is a condominium complex called the Residences at Dockside. This sixteen-story edifice was constructed atop the remains of Pier 30 South, once known as the Kenilworth Street Pier. The high-rise broke ground in 2000 and later opened as a rental community with 242 apartments. It went condo in 2006. As with Piers 3 and 5, the Delaware River flows underneath the ocean linerâshaped structure. Dockside is just one indication of the renewed appeal of living on Philadelphia's riverfront.

The most conspicuous indication is Waterfront Square Condominium, a three-tower multiplex just north of Spring Garden Street. This development is slated to have five buildings ranging from twenty-two to thirty-five stories with a total of 780 condominiums. That such a large, towering housing development should occupy this site would have dumbfounded Philadelphians a half century ago. The Waterfront Square compound totals ten acres, all of it made-earth.

G

AMBLING ON THE

D

ELAWARE

SugarHouse Casino is directly north of Waterfront Square. Philadelphia became the largest city in the United States to host a gambling casino when this venue opened for business on September 23, 2010. Lawsuits filed by neighborhood protesters and others delayed the opening for years. This was the strongest and most recent instance of conflict on the Delawareâother than the ongoing debate about river dredging.

SugarHouse gets its name from the Pennsylvania Sugar Refinery Company, situated on that property from 1881 to 1984 and employing over fifteen hundred men and women during World War II. The $355 million casino has brought attention to the potential of other development along Delaware Avenue in that section of town. Another casino was planned for the river's edge in South Philadelphia, but that project ran into difficulties.

The public clamor concerning SugarHouse disregarded the long history of gambling on the west bank of the Delaware going back to William Penn's era. When Quakers dwelled in riverbank caves, gambling went hand in hand with prostitution along the waterway. Betting occurred wherever sailors and pirates gathered to eat and drink, and tavern owners operated games of chance in their back rooms to meet the demand. This was happening well into the twentieth century.

Riverboat gambling had been proposed for the Delaware in the 1990s before standalone casinos were considered. But there was surely much gambling on the river for centuries.

20

T

HE

D

ELAWARE

E

XPRESSWAY

(I-95)

V

OILÃ

âA S

UPERHIGHWAY IN THE

M

IDST

[The]

deviation from

[William Penn's]

original plan

[for the Philadelphia waterfront]

is much to be regretted, as had that been adhered to, a pleasing view of the Delaware from Front street would have been obtained, and thus have not only added greatly to the beauty of the city, but have admitted a refreshing body of air from the river, and prevented the accumulation of filth, which, to the great injury of the inhabitants, has, and ever will be the consequence of the erection of dwellings in such confined situations

.

These words appear in

The Picture of Philadelphia

(1811) by Dr. James Mease (1771â1846). A local historian of the early 1800s, he lived and worked on the west side of Front Street next to Pine, so he must have known the story of William Penn's plans for the Delaware waterfront.

Maybe Dr. Mease wrote the anonymous piece about the embankment steps that appeared in the June 24, 1824 issue of the

Aesculapian Register

:

We are requested to ask whoever it may concern, by what authority the

public

stairs, running from Front to Water Street, are in several places shut upâand have been so for a great length of time. It was very proper during the yellow fever; but what has called for its continuance? If this is not soon obviated, what is

public

property will probably soon be claimed as private. It is highly probable that by some

entering wedge

like the present, the citizens have been deprived of that beautiful esplanade and fine prospect, which William Penn contemplated in the original plan of Philadelphia

.

A few of Penn's stairwells were thus blocked off during the Philadelphia's yellow fever contagions of the 1790s. They apparently remained closed for some time after, and this became a matter of public alarm. Some of the stairs were annexed by adjacent property owners, as the writer had foreseen.

But what the writer could not have foreseen was the heavy-handed threading of Interstate 95 through the city's waterfront. The Delaware Expressway has forever deprived citizens of the “beautiful esplanade and fine prospect, which William Penn contemplated in the original plan of Philadelphia”âmore than the construction of wharves and whatnot on the east side of Front Street ever did, let alone the closing or elimination of a few public stairways.

O

RIGINS OF

I-95

An elevated thoroughfare through Philadelphia's river district had been planned since 1932, when the Regional Planning Federationâpredecessor agency to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commissionâproposed a limited-access highway along the Delaware as part of a citywide parkway system. Plans languished until 1937, when a new proposal was issued, this time for an industrial highway dubbed the “Delaware Skyway” that would be built on top of Delaware Avenue.

Nothing happened until after World War II when engineers of the Pennsylvania Department of Highways reexamined the old plans and approved a route for the Delaware Expressway as part of the anticipated Interstate highway network. By 1955, a new plan called for a six-lane elevated artery through downtown Philadelphia alongside the Delaware River. It was revised again as an eight-lane arterial Interstate in 1959.

The Department of Highways started construction of the Philadelphia stretch that year under the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, but it was not until the late 1960s that the highway started to tear a path through the city's central waterfront. The recently established Independence National Historic Park fixed the roadway's location on the west and Delaware Avenue set its location on the east.

The Delaware Expressway was pursued with urban renewal in mind, too. Deserted and expendable warehouses and industrial sites were to be removed for both the highway and Penn's Landing.

W

HAT

'

S

T

HIS

A

BOUT A

H

IGHWAY

A

LONG THE

D

ELAWARE

?

Citizens and members of the Philadelphia City Council raised concerns with state and federal officials about the highway's location in the early 1960s. To assuage growing unease, the Department of Highways displayed a scale model of the road's downtown portion at Wanamaker's Department Store in 1963â64. The mock-up depicted an elevated expressway hugging the west bank of the Delaware and supported mostly with earth fill.

Upon seeing the model, architect Frank Weise (1918â2003) confronted Edmund Bacon. He warned the city planner that the freeway would cut off Center City from its historic waterfront and would doom the city's goal of populating the river's edge with housing, parks and shops.

Bacon was unwilling to intercede, telling Weise that he was not “living in the age of the automobile.” So the architect-turned-civic-activist organized a team of independent designers to develop an alternative scheme. This group, the Philadelphia Architects Committee, proposed an expressway that was both depressed and covered.

Meanwhile, increased public distress helped form the Committee to Preserve Philadelphia's Historic Gateway, chaired by attorney Stanhope Browne. This group looked to waterfront sites throughout the world for inspiration.

The two committees hired an engineering firm to evaluate the feasibility and cost of the substitute design. The resulting report was published as

The Proposal for a Covered Below-Grade Expressway Through Philadelphia's Historic Riverfront

(1965). This study reveals a colossal problem that engineers had to resolve in building the highway so close to the Delaware:

Because the Expressway is to be built near the Delaware River, water from that river would exert an upward thrust on the Expressway, which would in effect be floating in silt. To counteract this hydrostatic pressure, the

[Pennsylvania]

Department

[of Highways]

proposes to place the highway upon a concrete mat which in some places would be about 14 feet thick; the weight of the mat would be used to hold down the Expressway. The maximum depth of construction would be 37 feet below the 100-year high water level of the Delaware River

.

Builders of the Delaware Avenue Elevated had avoided this problem by constructing an elevated line rather than continuing the Market Street Subway through a city block of somewhat unstable made-earth to Delaware Avenue, which itself rests on made-earth.

Furthermore, the report considered and foretold the issues that became so clear after Highway 95 was completed:

If the current Department proposal is chosen, a trench containing ten lanes of traffic would become a dominant feature of the area, totally alien to its historic character. The old city would be forever separated from the riverfront where it originated. The Committee design, on the other hand, hides the massive scale of the expressway facility and prevents the ten lanes of automobile, bus and truck traffic from destroying the intimate living relation which Philadelphia's historic buildings have with each other and with the river

.