Pengelly's Daughter

For my husband Damian:

my very own Jim.

Contents

âThe tide rises, the tide falls,

The twilight darkens, the curlew calls.'

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Rising Tide

Chapter One

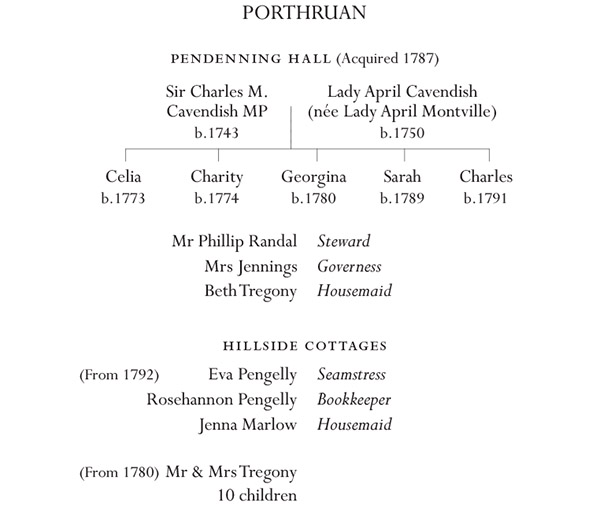

Porthruan

Monday 24th June 1793

âN

o, Mother. Never! I'd rather salt pilchards all my life than marry that man. Mr Tregellas is corrupt and dangerous. I'm sure he tricked Father into bankruptcyâ¦and you expect me to marry him?'

Flinching from my tone, Mother avoided my eyes. She had changed so much in the last year. Always so proud and hardworking, she was now fragile as a sparrow; her dress, with its invisible mending and reworked seams, drab and worn. She had aged, too, for her forty-ïve years. But it was her expression of resignation that frightened me â she was like a spring with no recoil.

âWe can make do,' I said more gently, guilty I had shouted so ïercely. âMy bookkeeping's bringing in some money and your sewing's paying the rent. We're managing well enough â we can go on as we are. There's no need for me to marry â least of all William Tregellas!'

Despite the warmth of the June sun shining so brilliantly outside, the parlour was cold and musty, the small, leaded window seeming to block, rather than admit any light. It was sparse and cheerless with dark patches of damp showing brown against the lime-washed walls. Two high-backed chairs faced the empty grate and a dresser stood crammed against the wall. I knelt by Mother's feet, taking hold of both her hands. They were worn and rough, her ïngertips reddened by excessive sewing. âI'll take care of you, Mother â we'll be alright.'

âI wish it was that easy,' she said. âSince your father died, Mr Tregellas's been very kind to us. We couldn't get Poor Relief and I didn't know what would become of us.' She began fumbling for her handkerchief. âI told you Mrs Cousins let us have this cottage cheap, but it wasn't true.' She held her handkerchief against her mouth, as if to stop her words.

âDon't tell me Mr Tregellas's been paying our rent! Don't tell me you've accepted money from that man!'

Her shoulders sagged. âI thought 'twould only be for a short whileâ¦' She hesitated, as if too scared to go on, ââ¦but that's not all. There was no public gift for your father's burial â Mr Tregellas paid for it all.'

âMother, no!'

âWhat else could I do?' The tears she was holding back now began to ïow freely. âWould you have your father rot with vagabonds? Lie alongside some stranger in a pauper's grave? What choice did I have? Mr Tregellas is a kind man and he's been good to us â he wants to help but you're too set against him to see any good in him. Andâ¦' Her voice turned strangely ïat, ââ¦over the past year, he's grown that fond of youâ¦and he doesn't want to wait any longer.'

I felt dizzy, sick, the walls of the room crushing against me as the unpalatable truth began to dawn: I was being bought by one and sold by the other, as surely as if I was a slave on the market block. âWhat arrangements have you made, Mother? I take it you

have

made arrangements?'

My fury made Mother wince. âRosehannon, think what he's offering â a position in society, a steady incomeâ¦servants. He's a respectable timber merchant and he's that taken with you â it would secure your future.' Her face took on a look of longing. âAnd we'd go back to Coombe House â to where your father always wanted us to live â instead of scratching a living in this damp cottage. Your father would want that.'

âFather? Approve of me marrying the man who cheated him?' I could not believe my ears. I missed Father desperately and needed his counsel so badly. Mr Tregellas had been manipulating Mother, I could see that now. He had been drawing her in like a ïsh on a line until he could land his catch â only, I was the catch. Bile rose in my throat. âPerhaps you should marry him, Mother â after all, he's nearer your age than mine!'

âYou know very well it's not an older woman he wants.'

âHe disgusts me and I'll not marry him. And that's all there is to it.' I lifted my skirts, striding angrily to the door.

Mother's voice followed me across the room. âThat's not quite all there is to it,' she said slowly. âHe's given us until your twenty-ïrst birthday â then he wants his answerâ¦or he'll call in his loan.'

âBut that's in three weeks' time!'

âI know,' she said, staring at the empty grate.

I thought I would faint. The room was spinning round me, pressing in on me. I needed to breathe the air that gave me courage. I am born of Cornwall, born from generations of ïshermen and boat-builders. The wind is my breath â the sea is my blood. I draw my strength from the remorseless gales that lash our coast, the waves that pound our rocks, the gulls that scream, the wind that howls. I needed to escape the close conïnes of that hateful cottage.

The door to the scullery was open. Wiping her hands on her apron, Jenna left the dough she was making, following me out to the sunshine. She had heard everything, of course. No need to press her ear against the crack in the parlour door, for we had spoken loudly enough. Strands of blonde hair were escaping from under her mobcap and ïour dusted her cheeks. With eyebrows raised and mouth pursed, she whistled in disbelief.

âWhat?' I said, pushing past her, scattering the hens in my anger.

âWill ye marry Mr Tregellas?'

âNo! Of course not!'

She took my arm, leading me across the yard. The stone step behind the back gate was far enough away, but near enough if Mother wanted either of us. Over the last year we had found ourselves sitting on it, more often than not, and it had borne witness to our growing friendship. Instinctively we made our way there, the warmth of the sun beginning to take the chill from my heart. âHere,' she whispered, her hand diving under her apron, âthese might help.'

Her dimples deepened. Wrapped inside a cloth were two apple dumplings. She handed me one and without another word, I took a bite. It was delicious â the suet light and ïuffy, the apple juicy and tart. Licking our ïngers, we leant against the gate, gazing across the grass to the cliff's edge. A soft sea breeze blew against our faces, rippling the grass in front of us. Behind us, our neighbour's gate began banging on its last hinge.