Outliers (15 page)

Louis Borgenicht, for example, left the impoverished home of his parents at age twelve to work as a salesclerk in a general store in the Polish town of Brzesko. When the opportunity came to work in

Schnittwaren Handlung

(literally, the handling of cloth and fabrics or “piece goods,” as they were known), he jumped at it. “In those days, the piece-goods man was clothier to the world,” he writes, “and of the three fundamentals required for life in that simple society, food and shelter were humble. Clothing was the aristocrat. Practitioners of the clothing art, dealers in wonderful cloths from every corner of Europe, traders who visited the centers of industry on their annual buying tours—these were the merchant princes of my youth. Their voices were heard, their weight felt.”

Borgenicht worked in piece goods for a man named Epstein, then moved on to a store in neighboring Jaslow called Brandstatter’s. It was there that the young Borgenicht learned the ins and outs of all the dozens of different varieties of cloth, to the point where he could run his hand over a fabric and tell you the thread count, the name of the manufacturer, and its place of origin. A few years later, Borgenicht moved to Hungary and met Regina. She had been running a dressmaking business since the age of sixteen. Together they opened a series of small piece-goods stores, painstakingly learning the details of small-business entrepreneurship.

Borgenicht’s great brainstorm that day on the upturned box on Hester Street, then, did not come from nowhere. He was a veteran of

Schnittwaren Handlung,

and his wife was a seasoned dressmaker. This was their field. And at the same time as the Borgenichts set up shop inside their tiny apartment, thousands of other Jewish immigrants were doing the same thing, putting their sewing and dressmaking and tailoring skills to use, to the point where by 1900, control of the garment industry had passed almost entirely into the hands of the Eastern European newcomers. As Borgenicht puts it, the Jews “bit deep into the welcoming land and worked like madmen

at what they knew.”

Today, at a time when New York is at the center of an enormous and diversified metropolitan area, it is easy to forget the significance of the set of skills that immigrants like the Borgenichts brought to the New World. From the late nineteenth century through the middle of the twentieth century, the garment trade was the largest and most economically vibrant industry in the city. More people worked making clothes in New York than at anything else, and more clothes were manufactured in New York than in any other city in the world. The distinctive buildings that still stand on the lower half of Broadway in Manhattan—from the big ten- and fifteen-story industrial warehouses in the twenty blocks below Times Square to the cast-iron lofts of SoHo and Tribeca—were almost all built to house coat makers and hatmakers and lingerie manufacturers and huge rooms of men and women hunched over sewing machines. To come to New York City in the 1890s with a background in dressmaking or sewing or

Schnittwaren Handlung

was a stroke of extraordinary good fortune. It was like showing up in Silicon Valley in 1986 with ten thousand hours of computer programming already under your belt.

“There is no doubt that those Jewish immigrants arrived at the perfect time, with the perfect skills,” says the sociologist Stephen Steinberg. “To exploit that opportunity, you had to have certain virtues, and those immigrants worked hard. They sacrificed. They scrimped and saved and invested wisely. But still, you have to remember that the garment industry in those years was growing by leaps and bounds. The economy was desperate for the skills that they possessed.”

Louis and Regina Borgenicht and the thousands of others who came over on the boats with them were given a golden opportunity. And so were their children and grandchildren, because the lessons those garment workers brought home with them in the evenings turned out to be critical for getting ahead in the world.

10.

The day after Louis and Regina Borgenicht sold out their first lot of forty aprons, Louis made his way to H. B. Claflin and Company. Claflin was a dry-goods “commission” house, the equivalent of Brandstatter’s back in Poland. There, Borgenicht asked for a salesman who spoke German, since his English was almost nonexistent. He had in his hand his and Regina’s life savings—$125—and with that money, he bought enough cloth to make ten dozen aprons. Day and night, he and Regina cut and sewed. He sold all ten dozen in two days. Back he went to Claflin for another round. They sold those too. Before long, he and Regina hired another immigrant just off the boat to help with the children so Regina could sew full-time, and then another to serve as an apprentice. Louis ventured uptown as far as Harlem, selling to the mothers in the tenements. He rented a storefront on Sheriff Street, with living quarters in the back. He hired three more girls, and bought sewing machines for all of them. He became known as “the apron man.” He and Regina were selling aprons as fast as they could make them.

Before long, the Borgenichts decided to branch out. They started making adult aprons, then petticoats, then women’s dresses. By January of 1892, the Borgenichts had twenty people working for them, mostly immigrant Jews like themselves. They had their own factory on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and a growing list of customers, including a store uptown owned by another Jewish immigrant family, the Bloomingdale brothers. Keep in mind the Borgenichts had been in the country for only three years at this point. They barely spoke English. And they weren’t rich yet by any stretch of the imagination. Whatever profit they made got plowed back into their business, and Borgenicht says he had only $200 in the bank. But already he was in charge of his own destiny.

This was the second great advantage of the garment industry. It wasn’t just that it was growing by leaps and bounds. It was also explicitly entrepreneurial. Clothes weren’t made in a single big factory. Instead, a number of established firms designed patterns and prepared the fabric, and then the complicated stitching and pressing and button attaching were all sent out to small contractors. And if a contractor got big enough, or ambitious enough, he started designing his own patterns and preparing his own fabric. By 1913, there were approximately sixteen thousand separate companies in New York City’s garment business, many just like the Borgenichts’ shop on Sheriff Street.

“The threshold for getting involved in the business was very low. It’s basically a business built on the sewing machine, and sewing machines don’t cost that much,” says Daniel Soyer, a historian who has written widely on the garment industry. “So you didn’t need a lot of capital. At the turn of the twentieth century, it was probably fifty dollars to buy a machine or two. All you had to do to be a contractor was to have a couple sewing machines, some irons, and a couple of workers. The profit margins were very low but you could make some money.”

Listen to how Borgenicht describes his decision to expand beyond aprons:

From my study of the market I knew that only three men were making children’s dresses in 1890. One was an East Side tailor near me, who made only to order, while the other two turned out an expensive product with which I had no desire at all to compete. I wanted to make “popular price” stuff—wash dresses, silks, and woolens. It was my goal to produce dresses that the great mass of the people could afford, dresses that would—from the business angle—sell equally well to both large and small, city and country stores. With Regina’s help—she always had excellent taste, and judgment—I made up a line of samples. Displaying them to all my “old” customers and friends, I hammered home every point—my dresses would save mothers endless work, the materials and sewing were as good and probably better than anything that could be done at home, the price was right for quick disposal.

On one occasion, Borgenicht realized that his only chance to undercut bigger firms was to convince the wholesalers to sell cloth to him directly, eliminating the middleman. He went to see a Mr. Bingham at Lawrence and Company, a “tall, gaunt, white-bearded Yankee with steel-blue eyes.” There the two of them were, the immigrant from rural Poland, his eyes ringed with fatigue, facing off in his halting English against the imperious Yankee. Borgenicht said he wanted to buy forty cases of cashmere. Bingham had never before sold to an individual company, let alone a shoestring operation on Sheriff Street.

“You have a hell of a cheek coming in here and asking me for favors!” Bingham thundered. But he ended up saying yes.

What Borgenicht was getting in his eighteen-hour days was a lesson in the modern economy. He was learning market research. He was learning manufacturing. He was learning how to negotiate with imperious Yankees. He was learning how to plug himself into popular culture in order to understand new fashion trends.

The Irish and Italian immigrants who came to New York in the same period didn’t have that advantage. They didn’t have a skill specific to the urban economy. They went to work as day laborers and domestics and construction workers—jobs where you could show up for work every day for thirty years and never learn market research and manufacturing and how to navigate the popular culture and how to negotiate with the Yankees, who ran the world.

Or consider the fate of the Mexicans who immigrated to California between 1900 and the end of the 1920s to work in the fields of the big fruit and vegetable growers. They simply exchanged the life of a feudal peasant in Mexico for the life of a feudal peasant in California. “The conditions in the garment industry were every bit as bad,” Soyer goes on. “But as a garment worker, you were closer to the center of the industry. If you are working in a field in California, you have no clue what’s happening to the produce when it gets on the truck. If you are working in a small garment shop, your wages are low, and your conditions are terrible, and your hours are long, but you can see exactly what the successful people are doing, and you can see how you can set up your own job.”

*

When Borgenicht came home at night to his children, he may have been tired and poor and overwhelmed, but he was alive

.

He was his own boss. He was responsible for his own decisions and direction. His work was complex: it engaged his mind and imagination. And in his work, there was a relationship between effort and reward: the longer he and Regina stayed up at night sewing aprons, the more money they made the next day on the streets.

Those three things—autonomy, complexity, and a connection between effort and reward—are, most people agree, the three qualities that work has to have if it is to be satisfying. It is not how much money we make that ultimately makes us happy between nine and five. It’s whether our work fulfills us. If I offered you a choice between being an architect for $75,000 a year and working in a tollbooth every day for the rest of your life for $100,000 a year, which would you take? I’m guessing the former, because there is complexity, autonomy, and a relationship between effort and reward in doing creative work, and that’s worth more to most of us than money.

Work that fulfills those three criteria is

meaningful

. Being a teacher is meaningful. Being a physician is meaningful. So is being an entrepreneur, and the miracle of the garment industry—as cutthroat and grim as it was—was that it allowed people like the Borgenichts, just off the boat, to find something meaningful to do as well.

*

When Louis Borgenicht came home after first seeing that child’s apron, he danced a jig. He hadn’t sold anything yet. He was still penniless and desperate, and he knew that to make something of his idea was going to require years of backbreaking labor. But he was ecstatic, because the prospect of those endless years of hard labor did not seem like a burden to him. Bill Gates had that same feeling when he first sat down at the keyboard at Lakeside. And the Beatles didn’t recoil in horror when they were told they had to play eight hours a night, seven days a week. They jumped at the chance. Hard work is a prison sentence only if it does not have meaning. Once it does, it becomes the kind of thing that makes you grab your wife around the waist and dance a jig.

The most important consequence of the miracle of the garment industry, though, was what happened to the children growing up in those homes where meaningful work was practiced. Imagine what it must have been like to watch the meteoric rise of Regina and Louis Borgenicht through the eyes of one of their offspring. They learned the same lesson that little Alex Williams would learn nearly a century later—a lesson crucial to those who wanted to tackle the upper reaches of a profession like law or medicine: if you work hard enough and assert yourself, and use your mind and imagination, you can shape the world to your desires.

11.

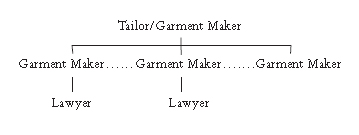

In 1982, a sociology graduate student named Louise Farkas went to visit a number of nursing homes and residential hotels in New York City and Miami Beach. She was looking for people like the Borgenichts, or, more precisely, the children of people like the Borgenichts, who had come to New York in the great wave of Jewish immigration at the turn of the last century. And for each of the people she interviewed, she constructed a family tree showing what a line of parents and children and grandchildren and, in some cases, great-grandchildren did for a living.

Here is her account of “subject #18”:

A Russian tailor artisan comes to America, takes to the needle trade, works in a sweat shop for a small salary. Later takes garments to finish at home with the help of his wife and older children. In order to increase his salary he works through the night. Later he makes a garment and sells it on New York streets. He accumulates some capital and goes into a business venture with his sons. They open a shop to create men’s garments. The Russian tailor and his sons become men’s suit manufacturers supplying several men’s stores....The sons and the father become prosperous....The sons’ children become educated professionals.