Oscar Wilde and the Murders at Reading Gaol: A Mystery (17 page)

Read Oscar Wilde and the Murders at Reading Gaol: A Mystery Online

Authors: Gyles Brandreth

Tags: #Historical Mystery, #Victorian

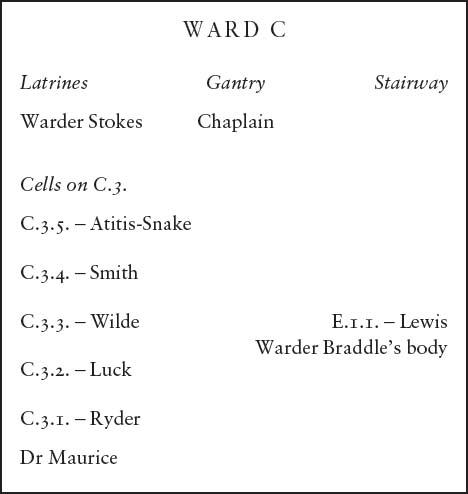

Dr Maurice considered the diagram carefully. ‘And Warder Braddle would not have been on his guard with the chaplain – as he would have been had any of the prisoners rushed out at him from their cells.’

Colonel Isaacson pushed his chair back from his desk and laughed. ‘That was not a serious suggestion, Dr Maurice. Why on earth would my chaplain murder one of my warders?’

‘Because he was commanded to do so?’ I suggested.

‘

Commanded

?’ thundered Colonel Isaacson. ‘Commanded by whom? The Almighty?’

‘By whoever has a hold over him,’ I said quietly. ‘That at least would provide us with a tenth suspect.’

‘The game is concluded, Doctor,’ said Colonel Isaacson. ‘Will you see that the prisoner is returned to his cell?’

13

Secrets

I

wore the obligatory cap of humiliation as a warder and the prison surgeon marched me back to my cell on C Ward. As we crossed the prison’s inner courtyard we passed a file of women prisoners returning to E Ward from their evening’s labour in the prison laundry. Night had fallen, but the February moon shone bright enough and, as she walked close by us, I studied the face of the wardress who I had seen smile at Warder Braddle. He had been dead four hours at least: she must have heard the news. But if his death had caused her any distress, her beautiful young face betrayed it not. She looked serene.

Once we had reached my cell, Dr Maurice dismissed the warder and, when the man had gone and the prison surgeon was certain that we were quite alone, he said, so softly that I had to strain to hear him, ‘Please sit down, Mr Wilde. I owe you an apology.’

‘I will sit, Doctor,’ I replied, ‘since you ask me and I am weary, but you should not call me “Mr Wilde” – I know that. That is what you told me when we first met.’

‘I remember.’

‘I am C.3.3. I am a prisoner in Reading Gaol. You are the prison surgeon. You have authority over me.’

‘All authority is degrading, Mr Wilde. It degrades those who exercise it and it degrades those over whom it is exercised.’

I smiled and looked down at the dish of cold skilly that had been left on my table for my supper. ‘I recognise the quotation, Doctor. You know my philosophy.’

‘I have been reading your work. Conan Doyle encouraged me to do so. He sent me one of your books for Christmas.’

‘I am flattered.’

‘It is not flattery, Mr Wilde. My admiration is sincere.’

‘But out of place in Reading Gaol, I fear.’

‘I see that.’

‘This interview with the governor just now was a mistake. I spoke out of turn.’

‘You were placed in an invidious position. The fault was mine. I meant for the best.’

‘I do not know how the governor allowed it,’ I said. ‘Or why.’ The doctor made no reply. In the gloom of the cell I could barely see his face. ‘You have a hold over him, I am sure. Doctors know secrets.’

‘I know nothing that would implicate the governor in Warder Braddle’s death.’

‘I am glad to hear it,’ I said. ‘Nor do I.’

The doctor threw up his hands. ‘But, Mr Wilde, ten minutes ago you suggested that the chaplain could have thrown Braddle to his death on the governor’s orders.’

I laughed. ‘I spoke for the sake of speaking, Doctor. It is my besetting sin. Colonel Isaacson would be much more likely to order Warder Stokes to dispose of Braddle – and Stokes, being younger and more biddable, would be much more likely to obey.’

‘But why should the governor want Braddle dead?’

‘Because Braddle usurped his power. Braddle threatened his authority. Braddle had “favourites”. Braddle was a law unto himself. He did as he pleased. That was evident for all to see – and Colonel Isaacson will not have liked that.’

The prison surgeon leant forward. ‘Mr Wilde, are you seriously suggesting that the governor of Reading Gaol arranged the murder of one of his own warders?’

I smiled in the darkness. ‘No, I am suggesting it playfully. You proposed the game, Doctor. I am merely playing it. The governor could well have wanted Braddle dead. He might have ordered his murder – or simply put the notion into someone’s head. “Who will rid me of this troublesome turnkey?” Colonel Isaacson did not commit the crime himself – we know that. At the time of Braddle’s fatal fall the governor was in the inspection hall – surrounded by witnesses. He did not do the deed, but he might have been its inspiration. Did Stokes do it – when he claimed to be in the latrines? Did the chaplain do it when he was alone on the gantry? Did you do it, Doctor – alone or with the chaplain? It would have been so much easier for two men to throw Braddle over the balustrade than one.’

The prison surgeon stood back, affronted. ‘Why in God’s name should I murder Warder Braddle?’

‘To please the governor? To appease the governor? To

implicate

the governor, perhaps?’

‘This is outrageous, Mr Wilde.’

‘I hope so, Dr Maurice. But do not protest too much. It was you, remember, who first warned me to beware of Warder Braddle. You must have had a reason. What was it, I wonder?’

‘The man was a menace,’ said the doctor quietly. He stepped away from me and stood with his back against the cell wall.

‘He was worse. He was a monster. Did you kill him, Dr Maurice? At four o’clock this afternoon, did you decide to make the world a better place and consign Warder Braddle to oblivion? Was it you who threw him to his doom?’

‘I could not have done so,’ said the doctor slowly. ‘I was with C.3.1. at the time.’

‘Ah, yes – so you say. But C.3.1. is sixty-eight and at death’s door. He is frail and old and easily confused. What is his testimony worth? And, come what may, he will be dead long before Warder Braddle’s murderer can be brought to trial.’

The doctor threw out his arms in supplication. ‘I did not kill Warder Braddle, Mr Wilde.’

‘I believe you, Dr Maurice,’ I answered gently. ‘And nor did I – though I confess, often, over many months, I wished him dead.’ I looked up at the prison surgeon, but in the obscurity of the cell I could not see the detail of his features. ‘Neither of us is a murderer, but someone in this prison is. Warder Braddle did not fall to his death by accident. And you are right, dear Doctor, my mind is atrophying. I want stimulus. I cannot read Dante in this gloom, but I can think – and I will. I shall unravel this mystery for you, if I can. I am one of the cleverest men in England, after all.’

The doctor laughed softly and moved towards the cell door.

‘Before you go, Doctor, may I ask a question?’

‘By all means.’

‘Where is Braddle’s body?’

‘In the prison morgue. Why do you ask?’

‘Before you leave the prison for the night, find yourself an oil lamp and inspect the body once again, if you will.’

‘What am I looking for?’

‘The unexpected,’ I said. ‘Some little detail that you failed to notice earlier in the immediate aftermath of the warder’s fall. It’s an axiom of Conan Doyle’s that the little things are infinitely the most important.’

‘I’ll do as you ask,’ he said, pulling open the cell door.

‘Thank you.’

‘Goodnight, Mr Wilde.’

‘Goodnight, Doctor. The game’s afoot.’

On the following morning, at the usual time, in the usual way, I stood leaning against my cell door, with my mouth and right ear resting against the hatch, awaiting my daily conversation with my Indian neighbour. It was my custom to let him speak first. His ears were more attuned to the rhythms of the prison than were mine. He could tell, more accurately than I could, when the coast was clear.

I waited longer than I expected. Eventually, I heard his whisper. ‘Are you there, Mr Oscar Wilde?’

‘I am,’ I said.

‘We must be careful. There may be changes to the roster because of what has happened. If I stop speaking quite suddenly, do not be surprised. For the next few days, we must be on the lookout for trouble. The other warders will be nervous. The atmosphere will be strange.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I understand.’

‘How are you today, Mr Wilde? Are you excited?’

‘Every death is terrible,’ I said.

Private Luck giggled. ‘Even one you desired from the bottom of your heart?’

‘Especially such a one.’

‘I am excited,’ said Luck. ‘I am jingle-jangling with excitement still.’

‘But you were one of the warder’s favourites.’

‘I know.’ He said it wistfully. ‘I know.’

‘Will you not miss his favours?’ I asked.

Luck laughed. ‘I had to work for them – at my age! And they were not so special.’

‘What were they, these favours?’

He paused. I wondered if he had heard a warder coming. I held my breath. ‘I was not beaten,’ he said at last.

‘That is something.’

‘And I got a sausage roll sometimes. And a cigarette. And the

Daily Chronicle.

That’s how I read about you, Mr Oscar Wilde.’

‘Warder Braddle brought you the newspaper?’ I asked, amazed.

‘The other prisoners cannot read and I do not drink. I did not want his stingo. It was disgusting. He brewed it himself. He was drunk yesterday. That made it easy.’

‘He was drunk, was he?’

‘He was very often drunk, Mr Wilde.’

‘Perhaps then he died happy,’ I said. ‘I hope so.’

‘I hope so, too,’ replied AA. ‘Let’s drink to that.’ He laughed at his own joke. ‘And are you happy now, Mr Wilde?’ he went on. ‘I hope so. I did my level best for you. You don’t have to pay until I am released, of course. You know that, don’t you? That will not be until next year, but I will need an IOU now – so there is no misunderstanding. What will you pay me? We did not agree an exact price, but you are a gentleman. You will pay me fairly, I know. I think one hundred pounds is right. Do you agree?’

My mouth was dry. My heart pounded. ‘I do not know what you are talking about,’ I whispered.

‘I killed Warder Braddle for you, Mr Wilde. I did as you asked. You must pay me. One hundred pounds is fair.’

14

Madness