Notebooks (27 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

Objects seen from the side on which the sun is shining will not show you their shadows. But if you are lower than the sun you can see what is not seen by the sun, and that will be all in shadow.

The leaves of the tree which are between you and the sun are of three principal colours, namely a green most beautiful shining and serving as a mirror for the atmosphere which lights up objects that cannot be seen by the sun, and the parts in shadow that only face the earth, and those darkest parts which are surrounded by something other than darkness.

The trees in a landscape which are between you and the sun are far more beautiful than those which have you between the sun and themselves; and this is so because those which are in the same direction as the sun show their leaves transparent towards their extremities and the parts that are not transparent, that is at the tips are shining; and the shadows are dark because they are not covered by anything. The trees, when you place yourself between them and the sun, will only display their light and natural colour, which in itself is not very strong, and besides this certain reflected lights which, owing to their not being against a background that offers a strong contrast to their brightness, are but little in evidence. And if you are situated lower down than they such parts of them may be visible as are not exposed to the sun, and these will be dark.

In the wind.

But if you are on the side whence the wind is blowing you will see the trees looking much lighter than you would see them on the other sides; and this is due to the fact that the wind turns up the reverse side of the leaves which in all trees is much whiter than the upper side; and, more especially, they will be very light if the wind blows from the quarter where the sun is, and if you have your back turned to it.

86

86

Describe the landscapes with wind and water and at the setting and rising of the sun.

All the leaves which hang towards the earth as the twigs bend with branches turned over, straighten themselves in the current of the winds; and here their perspective is inverted, for if the tree is between you and the quarter from which the wind is coming, the tips of the leaves pointing towards you take their natural position, while those on the opposite side which should have their tips in a contrary direction have, by being turned over, their tips pointing towards you.

The trees of the landscape do not stand out distinctly one from another; because their illuminated parts border on the illuminated parts of those beyond them and so there is little difference in lights and shades.

When clouds come between the sun and the eye all the edges of their round masses are light and they are dark towards the centre and this happens because towards the top these edges are seen by the sun from above while you are looking at them from below, and the same happens with the position of the branches of the trees; and also the clouds, like the trees, being somewhat transparent are partly bright and at the edges show thinner.

But when the eye is between the cloud and the sun the appearance of the cloud is the contrary of what it was before, for the edges of its rounded mass are dark and it is light towards the centre. And this comes about because you see the same side as faces the sun and because the edges have some transparency and reveal to the eye the part which is hidden beyond them; and which, as it does not catch the sunlight like that portion turned towards it, is necessarily somewhat darker. Again, it may be that you see the details of those rounded masses from the underside, while the sun sees them from above, and since they are not so situated as to reflect the light of the sun, as in the first instance, they remain dark.

The black clouds which are often seen higher up than those that are bright and illuminated by the sun, are thrown into shadow by the other clouds that are interposed between them and the sun.

Again, the rounded forms of the clouds that face the sun show their edges dark because they lie against the light background; and to see that this is true you should observe the prominence of the whole cloud that stands out against the blue of the atmosphere which is darker than itself.

87

87

The colours in the middle of the rainbow mingle together. The bow in itself is not in the rain nor in the eye that sees it; though it is generated by the rain, the sun, and the eye. The rainbow is always seen by the eye that is between the rain and the body of the sun; hence if the sun is in the east and the rain is in the west it will appear on the rain in the west.

90

90

At the first hour of the day the atmosphere in the south near to the horizon has a dim haze of rose-flushed clouds; towards the west it grows darker, and towards the east the damp vapour of the horizon shows brighter than the actual horizon itself, and the white of the houses in the east is scarcely to be discerned; while in the south, the further distant they are, the more they assume a dark rose, flushed hue, and even more so in the west; and with the shadows it is the contrary, for these disappear before the white. . . .

88

88

If you take a light and place it in a lantern tinted green or some other transparent colour you will see by experiment that all objects thus illuminated seem to take their colour from the lantern.

You may also have seen how the light that penetrates through stained glass windows in churches assumes the colour of the glass of these windows. If this is not enough to convince you watch the sun at its setting when it appears red through the vapour, and dyes red all the clouds that reflect its light.

89

3. THE LIFE AND STRUCTURE OF THINGS89

Although the painter’s eye sees only the surface of things it must in rendering the surface discern and interpret the organic structure that lies beneath. The representation of the human figure entails a knowledge of its anatomy and its proportions. Landscapes entail a study of the morphology of plants, of the formation of the earth, of the movements of water and wind.

This work must begin with the conception of man, and describe the nature of the womb and how the foetus lives in it, up to what stage it resides there and in what ways it quickens into life and feeds. Also its growth and what interval there is between one stage of growth and another. What it is that forces it out from the body of the mother, and for what reasons it sometimes comes out of the mother

’

s womb before due time.

’

s womb before due time.

Then I will describe which are the members which after the boy is born, grow more than the others, and determine the proportions of a boy of one year. Then describe the fully grown man and woman, with their proportions, and the nature of their complexions, colour, and physiognomy.

Then how they are composed of veins, tendons, muscles, and bones. Then in four drawings represent four universal conditions of men. That is, mirth with various acts of laughter; and describe the cause of laughter. Weeping in various aspects with its causes. Strife with various acts of killing: flight, fear, ferocity, boldness, murder, and everything pertaining to such conditions. Then represent Labour with pulling, thrusting, carrying, stopping, supporting, and such-like things.

Further, I would describe attitudes and movements. Then perspective concerning the function of the eye; and of hearing—here I will speak of music—and treat of the other senses—and describe the nature of the five senses. This mechanism of man we will demonstrate with [drawings of] figures.

91

(91

a

) Proportion

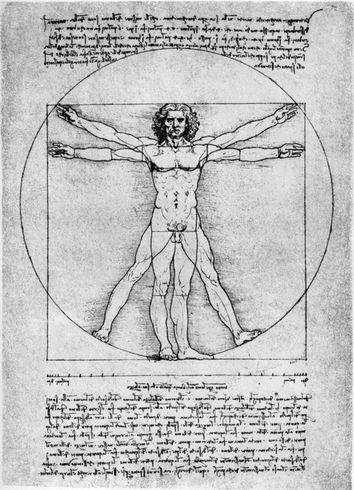

The theory of proportions had a great fascination for Renaissance artists. Their works were not only intended to display artistic skill, they were meant to achieve harmony. Proportions in painting, sculpture, and architecture were like harmony in music and gave intense delight.

Proportion is not only found in numbers and measurements but also in sounds, weights, time, and position, and whatever power there may be

.

.

The Roman architect Vitruvius had transmitted some data of a Greek canon for the proportions of the human figure and these were revived in the Renaissance. A drawing by Leonardo, known as the Vitruvian Man (Venice, Accademia), was reproduced in an edition of Vitruvius’ book, published in 1511, in order to illustrate the statement that a well-made human body with arms outstretched and feet together can be inscribed in a square; while the same body spread-eagled occupies a circle described around the navel. The proportions of the human body are here related to the most perfect geometric figures and may be said to be integrated into the spherical cosmos.

Leonardo endeavoured to verify and elaborate Vitruvius’ mathematical formulae in order to put them on a scientific basis by empirical observations, and for this purpose he collected data from living models.

Leonardo endeavoured to verify and elaborate Vitruvius’ mathematical formulae in order to put them on a scientific basis by empirical observations, and for this purpose he collected data from living models.

Geometry is infinite because every continuous quantity is divisible to infinity in one direction or the other. But the discontinuous quantity commences in unity and increases to infinity, and as it has been said the continuous quantity increases to infinity and decreases to infinity. And if you give me a line of twenty braccia I will tell you how to make one of twenty-one.

92

92

Every part of the whole must be in proportion to the whole . . . I would have the same thing understood as applying to all animals and plants.

93

93

From painting which serves the eye, the noblest sense, arises harmony of proportions; just as many different voices joined together and singing simultaneously produce a harmonious proportion which gives such satisfaction to the sense of hearing that listeners remain spellbound with admiration as if half alive. But the effect of the beautiful proportion of an angelic face in painting is much greater, for these proportions produce a harmonious concord which reaches the eye simultaneously, just as a chord in music affects the ear; and if this beautiful harmony be shown to the lover of her whose beauty is portrayed, he will without doubt remain spellbound in admiration and in a joy without parallel and superior to all other sensations.

94

94

The painter in his harmonious proportions makes the component parts react simultaneously so that they can be seen at one and the same time both together and separately; together, by viewing the design of the composition as a whole; and separately by viewing the design of its component parts.

95

95

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture* that the measurements of the human body are distributed by nature as follows: 4 fingers make 1 palm; 4 palms make 1 foot; 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height; and 4 cubits make one pace; and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in buildings.

If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height by

and spread and raise your arms so that your middle fingers are on a level with the top of your head, you must know that the navel will be the centre of a circle of which the outspread limbs touch the circumference; and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle.

and spread and raise your arms so that your middle fingers are on a level with the top of your head, you must know that the navel will be the centre of a circle of which the outspread limbs touch the circumference; and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle.

and spread and raise your arms so that your middle fingers are on a level with the top of your head, you must know that the navel will be the centre of a circle of which the outspread limbs touch the circumference; and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle.

and spread and raise your arms so that your middle fingers are on a level with the top of your head, you must know that the navel will be the centre of a circle of which the outspread limbs touch the circumference; and the space between the legs will form an equilateral triangle.The span of a man’s outspread arms is equal to his height.

From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth part of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the crown of the head is the eighth of the man’s height; from the top of the breast to the crown of the head is the sixth of the man; from the top of the breast to the roots of the hair is the seventh part of the whole height; from the nipples to the crown of the head is a fourth part of the man. The maximum width of the shoulders is the fourth part of the height; from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger is the fifth part; from the elbow to the end of the shoulder is the eighth part. The complete hand is the tenth part. The penis begins at the centre of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to just below the knee is the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to where the penis begins is the fourth part of the man.

Other books

Shadow of the Mountain by Mackenzie, Anna

President Fu-Manchu by Sax Rohmer

2 A Christmas Wedding To Die For by Pat Amsden

The Tutor by Andrea Chapin

Much Ado About Madams by Rogers, Jacquie

Deceit by Deborah White

Men in the Making by Bruce Machart

James Acton 01 - The Protocol by J. Robert Kennedy

Come, Barbarians by Todd Babiak

Ready or Not by Thomas, Rachel