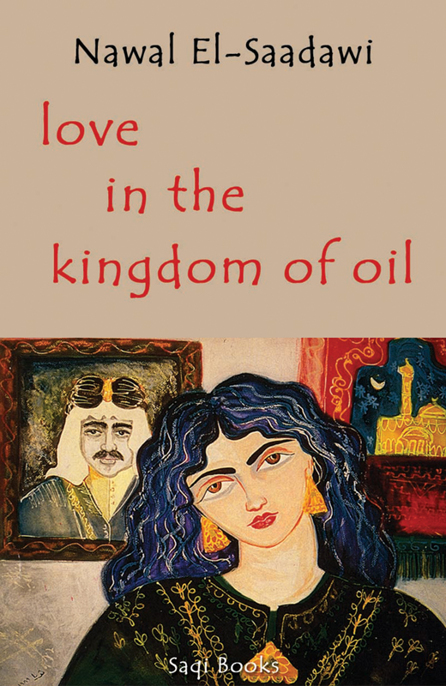

Love in the Kingdom of Oil

Love in the Kingdom of Oil

Nawal El-Saadawi

Translated from the Arabic by

Basil Hatim & Malcolm Williams

Saqi Books

That day in September the news appeared in the newspapers. Half a line of poor quality newsprint run off by the printers:

Woman goes on leave and does not return.

It was a normal thing for people to vanish. Every day the sun came out and so did the newspapers. In some corner of an inside page was a personal column. The word ‘personal’ could be suppressed or replaced by another word, without changing anything at all. Personal. Persons. People. The people. The nation. The masses. Words that mean everything and nothing at the same time.

On page 1 there was a coloured picture of His Majesty. Life size with a large title:

The King’s birthday party.

People rubbed their eyes. The corners of their eyelids were careworn. They turned over page after page. They yawned until their jawbones cracked. The news appeared on an inside page, scarcely visible to the naked eye:

Woman goes on leave and does not return.

Women do not go on leave. If one does, then she does so in order to run some essential errand. Before going, she must obtain written permission either in her husband’s hand or stamped by her boss at work.

There is no precedent for a woman going and not returning. A man can go and not return for seven years, but only if he stays away longer than that does the wife have the right to free herself from him.

The police began actively to search for her. They put out leaflets and adverts in the newspapers seeking to find her, alive or dead, and announced a generous reward from His Majesty the King.

‘What is the relationship between His Majesty the King and the disappearance of an ordinary woman?’

It almost goes without saying that nothing in the world can happen without an order from His Majesty, written or unwritten. His Majesty does not know how to read or write. That is a sort of privilege, because what is the point of reading and writing? The prophets did not know how to read and write, so is it possible for the King to be more virtuous than the prophets?

There was also the typewriter. It was an electric one. There was also a new, oil-powered typewriter. It wrote in all languages. Behind the typewriter there was a leather swivel-chair. On it sat a police commissioner. Above his head hung an enlarged picture of His Majesty the King in a gold frame, its borders replete with words from the sacred text.

‘Has your wife happened to go on leave before?’

Her husband clamped his lips shut in silence. His eyes widened like someone suddenly awaking from sleep. He was wearing his sleeping attire and the muscles of his face hung limp. He rubbed his eyes with his fingertips and yawned. He was sitting on a wooden chair fixed firmly on the ground.

‘No.’

‘Did you have an argument?’

‘No.’

‘Has she ever previously left the conjugal home without your consent?’

‘No.’

The investigation was taking place in a locked room. There was a red light hanging above the door indicating that nobody should enter. That way, there would be no leaks to the newspapers. The reports were kept inside a secret folder with a black cover. Written on it were the words: ‘Woman goes on leave.’

The police commissioner was sitting on a swivel chair. He swivelled round so that his back was to the wall and the picture of His Majesty. Opposite him was the other chair fixed to the ground. On it was sitting another man, not her husband but her boss at work.

‘Was she one of those women who are troublemakers and rebels against the established order?’

Her boss sat cross-legged. Between his lips was a black pipe that bent forward like the horn of a cow. His eyes stared upwards.

‘No, she was a submissive woman in every way.’

‘Could she have been kidnapped or raped?’

‘No. She was an ordinary woman who wouldn’t arouse in anybody a desire to rape her.’

‘What do you mean by that?’

‘I mean that she was a passive woman who aroused nobody’s passion.’

The police commissioner nodded his head indicating that he understood. He swivelled round in his chair so that his back was to her boss. He tapped with his fingers on the typewriter. A strange smell like burnt gas crept out. He stretched out his arm and adjusted the direction of the fan. Then he swivelled his chair round again.

‘Do you think that she has run away?’

‘Why should she run away?’

‘Nobody knows why a woman might run away. And if she has run away, where would she go? Could she have run away by herself?

‘Do you think she ran away with another man?’

‘Another man?’

‘Yes.’

‘Impossible. She was a totally honourable woman. Nothing occupied her apart from her work and her research.’

‘Research?’

‘She was working in the Research Section of the Archaeology Department.’

‘Archaeology? What’s that?’

‘It means discovering remains of old civilizations by digging up the ground.’

‘Like what?’

‘Old statues of the ancient gods like Amun and Akhenaton, or the ancient goddesses like Nefertiti and Sekhmet.’

‘Sekhmet? Who’s that?’

‘The ancient goddess of death.’

‘May God protect us!’

A report came in from the inspector of a remote station. A woman had been seen climbing into a boat. On her shoulders hung a leather bag with a long strap. She looked like a student or a university researcher. She was all by herself without a man. Something was sticking out of her bag. It had an iron head tapering into a sort of chisel.

The police commissioner became on edge. Drops of sweat appeared on his forehead. He pressed on a black button and the speed of the fan increased. It had a neck that allowed it to rotate gradually. The air in the room was almost suffocating.

‘Was the woman normal?’

On the nailed wooden chair sat a psychiatrist. His mouth was twisted towards the left, and the pipe with its stem curled like a horn tilting towards the right. His eyes stared at the upper half of the wall. The picture was in its gold frame. He exhaled a dense puff of smoke in the direction of His Majesty. Then he gave anxious attention to the policeman and turned his head in the other direction, where the fan was, and lowered his eyelids.

‘I don’t think she was a normal woman.’

‘Are you referring to her research?’

‘Yes. Usually a woman involved in matters outside the home is abnormal.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘A young woman throwing herself into a pointless job like collecting statues. Isn’t that an indication of illness or even perversion?’

‘Perversion?’

‘That chisel reveals everything.’

‘How’s that?’

‘In order to compensate for her unsatisfied desires, the woman takes enjoyment in burying the chisel in the ground as if it is a man’s penis.’

The police commissioner shuddered on his chair. He spun round a number of times like the fan. His fingers froze on the typewriter as he typed the words ‘penis’. He stopped typing and spun round with a swift movement.

‘It appears to be a serious matter.’

‘Indeed it is. I have written a number of pieces on this illness. From her childhood, the woman searches fruitlessly for the penis. And when she despairs of finding it, this desire changes into another desire.’

‘Another desire. Like what?’

‘Like looking at herself in the mirror. A sort of narcissism.’

‘May God protect us!’

‘Such a woman has a tendency to isolate herself, to keep silent and sometimes to steal.’

‘To steal?’

‘To steal rare artifacts and ancient statues. Especially ancient goddesses, for she is drawn towards people of her own sex and not the opposite one.’

‘May God protect us!’

‘At the same time, she is tempted with an urgent desire to disappear.’

‘Disappear!?’

‘In other words, a strong attraction towards suicide and death.’

‘May God protect us!’

‘In point of fact, when women look for archaeological remains, they feel great pleasure when they dig in the ground. They are drawn to the head of the chisel more than they are drawn to the head of the goddess Nefertiti. However much they try, they are unable to divert their eyes from the head of the chisel, as if it’s the organ they desire.’

‘Enough! Enough!’

The police commissioner was thoroughly perturbed. He stopped breathing completely. Then he began to pant. The chair spun round incessantly. The chair came to a stop and he took up the bottle of correcting fluid. He began to erase the word ‘penis’ from all the papers. However, the news filtered out to the press in spite of the red lamp. The reporters began to write about the subject shamelessly. News of the woman who had disappeared almost diverted people’s attention from the birthday celebrations of His Majesty the King.

The following day a royal decree was issued forbidding women to take leave and, if a woman did go on leave, it was forbidden to give her shelter or to conceal her.

* * *

That morning in September, a woman in the prime of youth went down to the landing stage. She had tied her thick black hair in two long plaits. She had wrapped the plaits three times around her head and they met above her forehead in a large bow. Her body was tall and slender inside a baggy gown that came down below her knees. Underneath it she was wearing a long baggy

sarwal

,

1

the legs of which were tied above her feet. From her shoulder hung a bag with a long leather strap. She held it tightly by the strap, and strode along with her eyes looking up like someone about to set sail towards the boats of the sun. The station inspector had stared at her with a natural curiosity. At the gate he had seen her extend her hand to the inspector to show him her ticket. The inspector gazed at it for a moment then returned it to her. She moved swiftly out of the station. There was nothing in her movements to arouse suspicion except that enthusiasm, uncommon among women, which she displayed as she looked towards the sun, with eyes bare of any covering, and something like the head of a chisel sticking out of her bag.

Boats were at anchor beside the landing stage, as usual waiting for passengers, and the woman headed for one of them. She climbed in unhesitatingly and occupied a seat at the back.

The woman stayed in the boat until the terminus, disembarked with all the other passengers and walked away. Nature displayed a mixture of strange colours, rivalling into one another and blending. The green of the grass, the yellow of the desert, the rusty red of the rocks, the blue of the sky and the white of the clouds.

She continued to stride along, holding her bag by the strap that was hung over her shoulder, as if she was moving willy-nilly towards a definite destination.

There were no longer any villages or large stretches of cultivated land. Instead, there were scattered fields and thorn trees. Then the soil changed and became sort of desert-like, black and fine, mixed with dark red as if it had been immersed in blood and then dried off under the sun. It stuck to her feet as she walked. From time to time clumps of date palms cast their shadow on the ground, appearing as if by chance, a stark black stain in the midst of the sand.

The woman stopped in the shade of a wall, perhaps for the first time since she had disembarked from the boat. She wiped her face with the sleeve of her gown to dry the perspiration. She began to gaze around her. She took the leather strap off her shoulder and opened the bag. She held the chisel in her right hand, and the bag in her left and moved off quickly again. She shook the soil off her feet, striking her heels on the ground a number of times. In the distance a large stretch of black water glimmered, resembling a stagnant lake.

Then her gaze swung round, passing over a low hill. A little village appeared, with houses made of black mud or some substance looking like mud, all huddled together. On the roofs were piles of garbage and upturned jars. The alleys were narrow and ended in cul-de-sacs. And then there was a large expanse of bare ground.

On the horizon was the top of a hill. The village stretched out below it. Massive pipes tore through it, gushing with what looked like black water. There were also wide-mouthed wells from which flowed a liquid resembling mercury; there was the smell of gas mixed with that of human beings, and something like salted sardines or kippers, and dead dogs on the dirt road that had been knocked down by vehicles speeding through the night.

The dirt road went downhill and the woman followed it. She walked fast, heading towards her goal, her bag slung over her shoulder by the strap. The village children were playing in a lake in front of the mosque. Old men were squatting on the bare ground, gazing fixedly at their toes and from time to time raising their eyes to heaven and gazing into space. A long string of women hidden under black

abayas

2

walked along slowly with jars on their heads.