Lost Worlds (9 page)

“You smoke bangi!”

There were more giggles at the side of me. I turned and my three pygmies were still sitting contentedly by the track, sipping their beers and nodding—“Bangi

—oui—

bangi.” What the hell is bangi? I thought. I must have actually said it too because the tall man with the bicycle started up again.

“Bangi is Zaire marijuana. They give you marijuana. You gone!”

Really? But I’d only taken a few casual puffs of their cigarette, spurred by politeness rather than intent. It must have been a powerful concoction indeed. One I could do without in the future.

“I make coffee. You be better.”

The man was being very considerate. Who was he?

“Where Jan put coffee?”

Oh, Jan’s friend. That’s right. The man from the village coming to look after the truck.

My head had rejoined my body and my mind seemed to be focusing better on the situation at hand.

“Behind his seat. In the canvas bag. I think.”

Soon I smelled the coffee bubbling in a battered pan on Jan’s tiny kerosene stove.

The man’s name was Amit or something that sounded like Amit. He brought my coffee in a chipped enamel mug. It was black, thick, and very strong.

“So—you like Zaire bangi?”

“Er—no, not exactly. I thought it was some kind of jungle cigarette.”

He laughed, exposing a huge mouth of bright white teeth. “Well—you right. Bangi is Efe tobacco. They smoke all the time. They say it makes them good hunters—I think it just makes them happy. All the time.”

“Well, they certainly seem happy.”

I turned and smiled at my three conspirator-companions. They smiled, giggled, and nodded. Then one of them spoke to Amit. Amit listened and translated.

“They would like to take you to their houses. In the forest. Would you like to go? Do you feel okay?”

“Another cup of this coffee and I could walk to Beni.”

He poured another cup out of the battered pan.

“So—would you like to go with them?”

“How will I get back to the road?”

“They will bring you back.”

“Where?”

“Here.”

“Right here?”

“Yes.”

“Is it a long journey?”

“Not so far. Maybe a few kilometers. Not far.”

“It’ll be dark in a few hours.”

“So—you can stay with them tonight. Come back in morning.”

“You’ll be here?”

“Of course. Jan has go to Mambasa and then come all way back. He will be long time. I will be here all night.”

“Are these good men? I don’t want any more of their bangi.”

“They good men. They are Efe. Efe are good people. They are forest people.”

I couldn’t think of any more questions to ask. I stood up, this time without falling down. The coffee had given me new energy—and sanity. I groped in my backpack for some chocolate I’d bought in Kisangani, offered it around, and gobbled the remnants myself.

“Okay, Amit. I’ll go.”

The pygmies seemed delighted and did a little bouncy jig by the side of the track, stirring up the red dust.

“Ah,” said Amit, “if you can see them when they dance…”

“Yes, Jan told me they love dancing.”

“It very big thing for them. Very important. Most Zaire people, we have forgotten the dances. But Efe live in deep places. They remember.”

I said good-bye to Amit and promised to be back early in the morning. I had no idea where I was, where I was going, or what would happen, but somehow I trusted the three little men who hopped around me and then led me off through the high grass and stands of whispering bamboo at the roadside and into the forest. Their forest.

It is difficult to explain what happened during the next few hours. Maybe it was the aftereffects of the bangi, maybe I was confused by the zip-zap sequencing of events, or maybe there’s real magic in the forest that doesn’t take kindly to crude revelations in written words.

There are stories that metaphorize the Ituri Forest as Eden, the first paradise on earth. Of course every nationality values, even reveres, its own country. The Balinese, the Nepalese, the Mongols, the Navajo, the Tuaregs of the Sahara, the Sri Lankans—each believe their land to be the most beautiful of places, the place where the earth, as we know it, began. And—being of a flexible and a generous nature—I usually agree with all of them. Beauty understood through the eyes of its beholder, and shared with that beholder, is beauty indeed. I have seen many places where the earth began and fell in love with each one of them.

But the Ituri Forest was something I’d never experienced before. There was something utterly overwhelming about its silence, its space, and its majesty. Enormous trees, with roots that eased out of the earth like the smooth backs of dolphins, rose scores of branchless feet into twilit canopies, where they exploded in soft profusions of sun-dappled leaves and vine flowers of purple, yellow, and scarlet. Hundreds of air plants (epiphytes) drooped over the topmost branches like shaggy-haired kittens. Vines hung down like hairy ropes, inviting me to climb into the uppermost reaches and explore the busy territories of the white-nose and blue monkeys, the hornbills, and dozens of other species who rarely if ever visit the open forest floor.

I hadn’t expected such openness. In other rain forests I’d explored, particularly in South America, the layering of the plant species was far more intense and frenzied. Here I walked through the equivalent of an English beech forest, bouncing on the moist, mulchy earth, admiring its rich range of bronzes, ochers, and golds. There was no need for panga knives to cut through the brush. There was hardly any brush. No stinging plants, no vicious thorns, no sticky fly-catchers, no razor-edged leaves. Only a few smaller trees and occasional flurries of fat-leaved bushes, but mostly space and cool air that seemed to fill my body with sweetness and wonderful calming silences in the green half-light.

How different this was from the tangle of Panama’s Darien jungle and the impenetrable tumult of Tasmania’s rain forests. I walked as if floating—effortlessly, easily through the quietude—following my three guides, who strolled barefoot across the soft surface, barely making a sound.

Two lines from Baudelaire that Paul had shown me on the boat seemed to capture both the magic and the mystery of the forest:

Nature is a temple in which living columns sometimes emit confused words.

Man approaches it through a forest of symbols which observe him with familiar glances.

(I particularly like the “familiar glances.” Sometimes I sense that.)

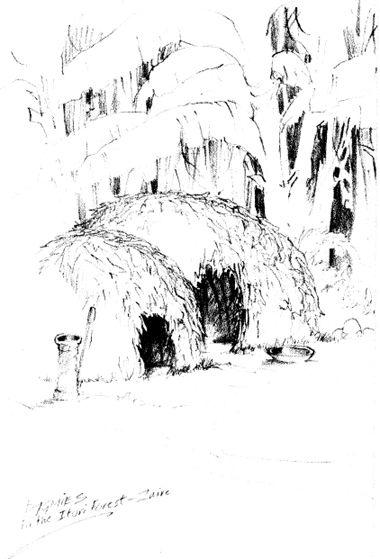

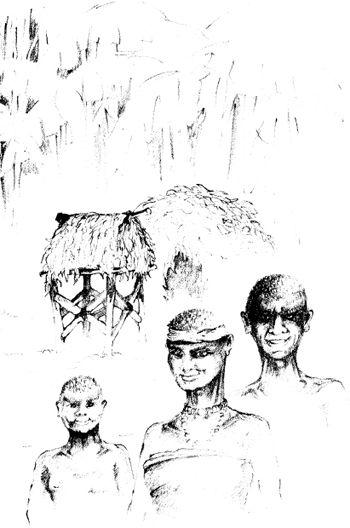

It was evening when we arrived in a slight hollow on the forest floor. The cicadas were off again, making their ritual, ear-scratching racket. Fires were burning in the soft half-light and I could see five domed huts in an arc around a larger fire. Shadows flickered across the hollow and on the bushes and tree trunks. Figures moved about—children, young girls with faces painted in red and black lines, and older women, all naked except for loincloths made from a thin bark.

My three companions were greeted with broad smiles and laughter. Some of the women began singing quiet simple songs, more like mantras, as they pounded manioc with heavy wooden pestles.

We all sat down by the large fire and a boy, thin and coyly shy, carried a three-foot-long tube of bamboo and placed it in the hands of one of the men. It was a communal pipe with a small bowl already filled with compressed bangi leaves. The man reached out to the fire, scooped up a few glowing embers, placed them on top of the bangi, and inhaled deeply. Blue smoke rose again in those now-familiar curlicues. I decided not to stare at the ever-changing shapes in fear of starting up the whole hallucinatory process again. And, as politely as I could, I declined to participate as the pipe was passed around the circle. I needed no stimulants that night. It was enough just to be here, deep in the forest with its night cries and curious sighing sounds. (Breezes in the canopy? Or the soft breathing of the forest gods that the pygmies revered and their Bantu cousins feared?) I was happy to listen to the sleepy chirps and coos of invisible flycatchers, warblers, sunbirds, and pigeons high in the canopy; I was content just to be here with these friendly people, the last authentic hunter-gatherers on earth, who seemed to accept me so openly, without undue curiosity or the banter of bad-English questions that had bombarded me elsewhere in Zaire.

Other men joined us by the big fire. The women, still humming softly, sat with their pots by the fires preparing food or weaving intricate nets of liana rope, which, I learned later, the pygmies used for hunting duikers and other species of miniature antelope.

The pipe was refilled and continued its way, mouth to mouth, around the main fire. One of the men began a low, guttural chant, his chest reverberating like a taught drumskin. Others joined in, imitating the sounds of forest birds. They swayed together to the slow rhythm in a haze of bangi smoke.

Someone—another young boy—began a delicate dance in the flickering shadows beyond the fire, stirring up little clouds of dust. He seemed to be playing two roles, first as a hunter in the forest, carefully stalking on tiptoe; then he became the prey, possibly a small antelope, low to the ground, moving, then pausing, sniffing the air, then moving on again. The men turned to watch, emitting the long sad cries of an antelope. The boy hesitated, depicting the confusion of the animal. The cries continued. The boy imitated the long, leaping run of the antelope, darting in and out of the shadows. The men began to clap quietly—the antelope became more alarmed, leaping harder and faster, whirling through the dust clouds. The clapping increased—the antelope ran—the clapping got louder—the boy suddenly did a somersault and thrashed his legs and arms about, depicting the animal’s entanglement presumably in one of the hunting nets the women were weaving by the huts. The men suddenly leapt up from the fire, surrounded the boy captured in the imaginary net, and began a rapid circular dance around his writhing form. Six, seven, eight times they danced around him, clapping and laughing. Then they stopped as suddenly as they’d begun. One man knelt down and with an imaginary panga knife slit the throat of the boy-antelope. The boy gave a rather too realistic shudder and lay still among the settling dust.

There was a brief silence followed by soft laughter from the women and wild leaps from the men. The boy rose up, smiled, and vanished into the shadows. The men continued their leaping and laughing and then, one by one, returned to sit by the fire and resume their bangi smoking.

The whole event lasted only a few minutes. It had been so impromptu, so casually introduced and ended, that for a while I wondered if I’d imagined it all, swept away again in a hallucinatory haze from all that bangi smoke. But then the boy joined us by the fire and the men slapped his back and thighs, congratulating him on a fine performance. A small intense ritual deep in the forest, not for me, but for themselves. A reaffirmation of their own lives and their links with the life of the forest itself. A part of their daily rhythm, as natural as sleeping or eating.

And eating is what we did next. The women carried chunks of hot meat and wild yams from their cooking pots on large green leaves and handed each of us a hefty portion. I suddenly realized how hungry I was. I hadn’t eaten anything except half a bar of melted chocolate since my breakfast of coffee and cheese with Jan.

The meat was delicious—sweet, tender, and full of juice. The men seemed to be speaking the lingala language, of which I understood almost nothing. But they knew I was curious about the animal origins of our dinner and pointed, with gales of laughter, to the boy, the dancer, who was eating with us. I understood and laughed with them. I was eating antelope or duiker, the creature imitated in the boy’s dance. I praised the meal so profusely that the women brought me two more enormous helpings and stood grinning behind the men, watching me eat every mouthful, washed down with a communal bowl of what I think was home-brewed palm wine. It was a sweet, seemingly innocuous concoction, but after four long gulps I felt wonderfully light-headed and sleepy.