Lost Worlds (16 page)

Nowadays there are other, less elusive spirits protecting the Llanos—the spirits of infrequent visitors to this strange land who share the visions of Doña Barbara, the Estradas, and other enlightened ranchers, and hope for its preservation.

I add my hopes to theirs.

The story had a certain appeal.

There was once a wise young man who was a judge and a highly respected citizen of a small town in the Andean region of Venezuela. One day in 1943 without warning he decides to dump all the honors and material benefits of a secure and prosperous life and, along with his wife, goes off over the mountain passes to a remote valley cut off from the world. There he builds a primitive house out of rocks, grows his own food, rears his own livestock, and lives a simple, silent existence.

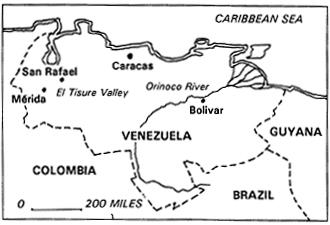

For a long time nothing is heard of the man until tales begin to trickle down from the jagged peaks of the Sierra Nevada range to the towns of the Mérida Valley. Tales of a church he has built by himself, stone by stone, with a tall tower and bells, of wooden carvings depicting Calvary and the saints of Christendom, of beautiful rugs and cloth woven by the man on his own loom. Tales too of the man’s wisdom and his kindness to occasional strangers who wander into his lonely outpost in the valley of El Tisure. Eventually his reputation as the guru of the mountains encourages arduous pilgrimages by hardy souls in need of advice and spiritual nurture….

As I said, the story had a certain appeal.

I’d come to Mérida, the charming little “City of Gentlemen,” a few days before in search of Venezuela’s Andean grandeur and had found it in abundance. High above the narrow Spanish-flavored streets and churches of this regional capital rose the soaring Sierra peaks and ranges, snowcapped and shining in a warm spring sun. Glaciers sparkled among the arêtes of Pico Bolívar (16,427 feet), the tallest mountain in Venezuela.

I had taken the cable car (

teleferico

), the longest and highest in the world, up the slopes of Pico Espejo (15,634 feet), and gasped for elusive oxygen while photographing the mountain ranges and the statue of the Virgin of the Snows overlooking the Colombian border. I had explored the city’s markets, marveled at the opulence of a wedding at the cathedral, watched Ecuadorean folksingers in the Plaza Bolívar play their strange flutes and odd-shaped guitars, heard the wild cheers of the crowd at the municipal cockfight, enjoyed the hearty—and typically inexpensive—steaks and fresh trout dinners in the city’s traditional restaurants, and danced till I dropped to the sambas and tangos of Mérida’s pre-Lent carnival.

But—as always—I was restless for adventure. Something different, something challenging. Something more than trinkets and travelers’ souvenirs to take back home. Something with meaning and endurance.

A journey to find the hermit of El Tisure! What a fine climax to my stay in this beautiful and wild region. I needed a bit of quiet wisdom and insightfulness anyway to balance the hedonistic pace of Mérida.

So that’s how I came to be sitting on this mule, under a brilliant blue sky, heading slowly away from the Mérida Valley and climbing ever higher toward a fourteen-thousand-foot pass over the mountains and into the secret wilds beyond—the “lost world” of El Tisure.

My young bright-eyed guide Paco, always smiling (and occasionally laughing at my antics to mount and control my headstrong mule), let me saunter ahead on the stony track while he murmured softly to his own well-behaved horse and cajoled an irritable donkey carrying our supplies and equipment.

We passed the tiny stone farmhouses on the lower slopes occupied by the

minifundista

, the small landowners of the Andes. Some of the fields on the steep hillsides had been leveled in terrace fashion based on the ancient

poyos

originally constructed by the Timoto-Cuica Indians. But most were merely cleared of stones, which now formed miles of serpentine stone walls and were plowed horizontally with the contours by teams of enormous oxen. I tried to photograph them, but my mule refused to stop.

It was so good to be away from the city and among the broken treeless hills of the

paramo

uplands, swaying through sweeping pastures of yellow

frailejon

flowers, whose pale green stems and leaves were coated in white velvety fur. Venezuelans have a soft spot for the wild

paramo

and its characteristic hardy plant. They write songs and poems about it, claim dramatic medical properties, blend the pith into a kind of jam, and wrap home-churned butter and little goat cheeses in its fuzzy leaves to give them “perfume.” When nothing much else grows in the high Andean ranges but spiky grasses, heather, and mosses, you have to admire its tenacity, and beauty. A hillside of golden

frailejon

flowers is a soul-warming sight.

We paused for a lunch of fruit and coarse

arepa

cornbread. I had watched Paco’s mother bake the small rounds in her rock-walled kitchen in San Rafael. The tiny room had no chimney and blue smoke, cut by shafts of sunlight through a tiny window overlooking the pig pound, wraithed around our heads before slowly easing through chinks in the pantile roof. She was a small plump woman with one of those strong Indian faces that seemed to be hacked out of Andean gneiss. But when she smiled through the smoke her features immediately softened into girlish femininity. I liked her, even though I couldn’t understand a word of her soft chatter. And I think she liked me too because she picked our lunch loaves very carefully, smelling each one, tapping the hard, almost black crust with her fingers before wrapping them in cheesecloth and sending us off into the hills with a blessing and a final smile.

We let the horse, the mule, and the donkey graze by a stream which tumbled over large boulders into a deep pool, clear as uncracked crystal. It was hot in the sheltered spot we’d selected for lunch, out of the valley breezes. The water was tempting, so I stripped off and plunged in.

And almost plunged right out again. The pool was virtually ice and the hot sun made it seem even colder.

Paco laughed through his mouthful of

arepa

, spraying crumbs. In his broken Spanish-English I heard him explain that the water in the stream had come from melting snow and ice fields in the mountains high up above the pass.

I tried to fake nonchalance as I splashed about, aware that my body was rapidly losing all feeling.

“It’s fine, Paco. Once you get used to it, it’s fine. Come on in!”

Paco shook his head and continued spraying

arepa

crumbs. But, to be honest, it

was

fine after a while. My torso emerged tingling and invigorated and I lay back in the grass to let the sun dry me, enjoying the tickling sensations as veins began to run again.

After lunch the narrow path began to rise more steeply toward a vast wall of rock that seemed to grow higher and more ominous as we guided our animals between the broken boulders. Where was the pass? I looked for an inviting cleft between the jagged mountains, but all I could see was that rock face. Surely we weren’t going to clamber over that thing?

Apparently we were.

The path zigzagged across more screes of sharp rocks, descended into clefts, crossed tumbling streams, and then climbed ever higher, heading straight for what looked like the insurmountable barrier. Maybe you’d make it with ropes and pitons, but with animals and a donkey laden with packs of food and sleeping bags and cooking equipment? Crazy idea! No wonder the wise old man who’d cast off all society’s trappings was known as “the hermit.” He’d discovered a place well and truly shut off from the world. Well, he’d better live up to all the tales told about him. This was going to be a far harder journey than I’d first thought.

Back in Mérida, when I announced my plans to a few friends I’d made in the city, there’d been raised eyebrows, low whistles, and decidedly cynical grunts. But no one warned me I’d be climbing vertical rock faces and maybe using up yet one more of my catlike lives. They were envious. I could feel it. Maybe a little resentful that I could travel where I wished, allowing all the time needed, while they stayed home in the city living responsible, hardworking lives.

Well. It was my fault for maybe being a little too dismissive of the challenges and not doing enough background research on what I was letting myself in for. And now I could hardly change my mind. I was in it for the duration. I couldn’t go back and explain that it was a more difficult journey than I’d bargained for. After all, we world wanderers (even this rather overweight one) have a certain reputation to keep. And they’d given me a wonderful farewell dinner, plied me with excellent wines, and toasted to my success. I had to succeed, for them—and for me.

So—onward and upward.

And upward and upward.

The rock wall now loomed like the Hoover Dam over us. I could see clouds across the high crags being slit to ribbons by the frost-shattered ridges.

Then the real climbing began. Surprisingly there was a path of sorts between piles of smashed rocks, but it was too steep for mule riding. We dismounted and began to drag our reluctant mounts higher and higher up the cliff face.

At eight thousand feet in San Rafael, where I’d arranged for my guide and transport, the air had been invigorating, full of the scent of flowers. Now we were around eleven thousand feet and I was aware of diminishing oxygen. My breaths were shorter and my body complained of thin air. I stopped leading the mule and let him make his own way up the narrow path. I had enough problems dragging my own weight up the steep face.

I tried not to look up. It was just too depressing to see the wall looming above me. Step—inhale—step—exhale. A slow steady rhythm was best. One step after the next, allowing the hypnotic pace to reduce thought to the now and nothing more.

Paco seemed unfazed by our change of pace. He’d made this journey before and didn’t mind telling me.

“This is the easy bit,” he called out, grinning like an idiot.

Thank you, Paco. Just what I needed to hear.

And of course he was right. Compared to what came later, this was a country ramble.

It became colder too. The mists were beginning to creep down the rock face. The top of the pass was blocked from sight by swirling wraiths of ribboning cloud. Soon we disappeared entirely into the cloying dampness. At times I lost the path and had to clamber back over mossy boulders to find my way again.

After two hours of this I was drained of all energy. Only the mental rhythm—step, inhale, step, exhale—kept me moving ever upward. Pilgrims seeking out the lonely hermit must really be burdened with problems to make this journey. I wondered what comforts they brought back with them. Apparently Juan Felix Sanchez, for that was his name, was known to speak in elliptical wisdoms, zenlike in their simplicity—or complexity, depending on your attitude. I’d heard similar tales in Nepal of mountain-bound gurus to whom the frantic faithful flocked in search of insights and gleamings of timeless knowledge. They say you value what you struggle for. In which case this was going to be a most enlightening journey.

The rock wall was almost vertical now. Somehow the animals climbed surefooted up the serpentine path, which was only a couple of feet wide. I was puffing and wheezing like a leaky steam engine. It was only that pungent quote from Shakespeare’s

Macbeth

that kept me going:

…stept in so far that

Returning were as tedious as go o’er

Paco was at the rear, still smiling and cajoling the donkey who, every few minutes, would bray out his anguish at having to carry our hefty load of food and equipment up such a ridiculously steep path.

Upward and upward; thirteen thousand feet and still climbing.

We were now totally smothered in the mist. Nothing existed outside the pounding of my heart, the rasp of my oxygen-starved lungs, and the scratch of boots on hard rock.

Upward and upward.

Surely we must be near the top of the pass by now. It was getting darker. My watch told me it was six-thirty

P.M.

, too late to make it down the other side in safety. That meant a night on the mountain. Not a welcome thought. We’d obviously set out on the journey too late in the day. Paco had warned me about this, but I’d ignored him in my enthusiasm for getting started. An enthusiasm that had now diminished to surly resentment at the fickleness of these mountains.

Then suddenly all my mumbling and grumbling ceased as a blast of frigid wind tore at my wet parka and almost sent me tumbling backward down the rock wall. My eyes were reduced to narrow slits and I could see nothing in front of me except slabs of ice-coated rock. But at least they were horizontal slabs, not vertical. Like a graveyard of fallen headstones. The top of the pass!

There was little time or enthusiasm for rejoicing. We both pulled our hoods tightly around our faces and tried to take shelter behind a boulder as the wind and clouds tore past us.

Paco had to shout to make himself heard in the maelstrom.

“Welcome to La Ventana—“the place of the winds”! We go down a little way. Find somewhere out of the wind. Make camp.” Then he added ominously. “This is not good. We leave too late.”

Yes, Paco, I know. And it was my fault.

The animals sensed our moroseness. They too knew things had gone wrong and made odd whinnying noises, beginning the descent warily, placing their feet delicately on the loose icy rocks of the path.

Fortunately, as we moved lower, the wind dropped. By nine-thirty

P.M.

we had found a sheltered spot in a rough circle of tumbled boulders and agreed to stop and spend the night. There were patches of brittle grass and

frailejon

, so at least the animals would have something to eat. We untied the packs and pulled the rolled sleeping bags off the shivering little donkey.

“You want some soup?” asked Paco.

“Great idea,” I think I said as we both scrambled into our waterproof sleeping bags, but I don’t remember anything else. Maybe Paco cooked and drank some soup, but I was already asleep, cocooned in duck down and dreaming of those long, leisurely dinners I’d enjoyed with my friends back in the cozy candlelit restaurants of Mérida that now seemed so far away….