London (2 page)

PREFACE

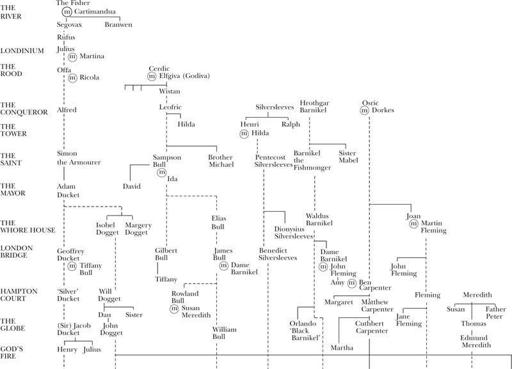

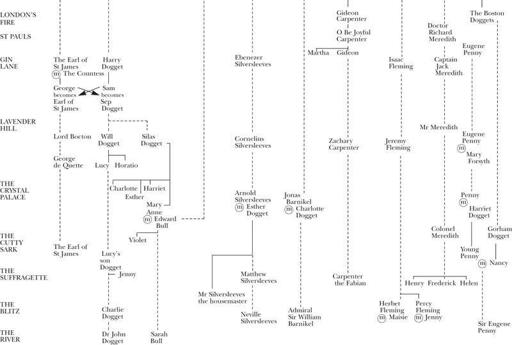

London is, first and foremost, a novel. All the families whose fortunes the story follows, from the Duckets to the family of Penny, are fictitious, as are their individual parts in all the historical events described.

In following the story of these imaginary families down the centuries, I have tried to set them amongst people and events that either did exist, or might have done. Occasionally it has been necessary to invent historical detail. We shall probably never know, for instance, the exact place where Julius Caesar crossed the Thames: to this author, at least, the site of present-day Westminster seems the most logical. Similarly, though we know the political circumstances in which St Paul’s was founded by Bishop Mellitus in 604, I have felt free to make my own guess as to the exact situation at Saxon Lundenwic then. Much later, in 1830, I have invented a St Pancras constituency for my characters to contest in the election of that year.

But generally speaking, from the Norman conquest onwards, such a rich body of information has been preserved not only concerning London’s history but also the life stories of countless individual citizens, that the author has no shortage of detail and only needs, from time to time, to make small adjustments to complex events in order to aid the narrative.

London’s chief buildings and churches have nearly always kept their names unchanged. Many streets, too, have retained their names since Saxon times. Where names have changed, this is either explained in the course of the story; or if this would be confusing I have simply used the name by which they are best known today.

Inventions belonging to the novel are as follows: Cerdic the Saxon’s trading post is placed roughly on the site of the modern Savoy Hotel; the house at the sign of the Bull, below St Mary-le-Bow, may be presumed to stand on or near the site of Williamson’s Tavern; the church of St Lawrence Silversleeves near Watling Street might have been any of several small churches in this area which disappeared after the Great Fire; the Dog’s Head could be one of a score of brothels along Bankside.

I have, however, allowed myself to place an arch at the location of today’s Marble Arch, in the days when this was a Roman road junction. It is not impossible that there really was such an arch – but its remains have yet to be found!

Of the fictional families in the story, Dogget and Ducket are both quite common names, often found in London’s history. Real individuals bearing these names – in particular the famous Dogget who instituted Dogget’s Coat and Badge Race on the Thames – are occasionally mentioned in the text and clearly distinguished from the imaginary families. The derivations of the fictional families’ names and their hereditary physical marks are, of course, entirely invented for the purpose of the novel.

Bull is a common English name; Carpenter is a typical occupational name – like Baker, Painter, Tailor and dozens of others. Readers of my novel

Sarum

may recognize that the Carpenters are kinsmen of the Masons in that book. Fleming is another frequently encountered name and presumably indicates Flemish descent. Meredith is a Welsh name and Penny can be, though is not necessarily, Huguenot. The rarer name of Barnikel, which also appears in

Sarum

, is probably Viking and its origin associated with a charming legend. Dickens made use of this name (Barnacle) but in a rather pejorative way. I hope to have done a little better for them.

The name of Silversleeves however, and the long-nosed family of this name, is completely invented. In the middle ages there were many more of these delightful and descriptive names which, sadly, have mostly died out. Silversleeves is intended to represent this old tradition.

A writer preparing a novel on London faces one enormous difficulty: there is so much, and such wonderful material. Every Londoner has a favourite corner of the city. Time and again one was tempted into one or another fascinating historical by-way. There is hardly a parish in London that could not provide material for a book like this. The fact that

London

is also, to a considerable extent, a history of England, led me to choose some locations over others; but I can only hope that my choice will not prove too disappointing to the many who know and love this most wonderful of cities.

THE RIVER

Many times since the Earth was young, the place had lain under the sea.

Four hundred million years ago, when the continents were arranged in a quite different configuration, the island formed part of a small promontory on the north-western edge of a vast, shapeless landmass. The promontory, which jutted out in a lonely fashion into the great world ocean, was desolate. No eye, save that of God, beheld it. No creature moved upon the land; no birds rose in the sky, nor were there even fish in the sea.

At this remote time, in the south-eastern corner of the promontory, a departing sea left behind a bare terrain of thick, dark slate. Silent and empty it lay, like the surface of some undiscovered planet, the grey rock interrupted here and there only by shallow pools of water. Under this layer of slate, deep in the Earth, pressures still more ancient had raised up a gently shelving ridge some two thousand feet high, which lay across the landscape like a huge breakwater.

And thus the place long remained, grey and silent, as unknown as the endless blankness before birth.

In the eight geological periods that followed, during which the continents moved, most of Earth’s mountain ranges were formed, and life gradually evolved, no movements of the Earth disturbed the place where the slate ridge lay. But seas came and departed from it many times. Some of these were cold, some warm. Each remained there for many millions of years. And always they deposited sediments hundreds of feet thick, so that at last the slate ridge, high though it was, became covered, smoothed over and buried deep below, with scarcely a hint that it existed.

As life on Earth began to burgeon, as plants covered its surface and its waters teemed with creatures, the planet began to add further layers formed from this new, organic life it had brought into being. One great sea that departed about the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs, let fall such a prodigious quantity of detritus from its fish and plankton that the resulting chalk would cover much of southern England and northern France to a depth of some three hundred feet.

And so it was that a new landscape came into being, above the place where the ancient ridge lay buried.

It was a different shape entirely. Here as other seas came and went, and huge river systems from the interior drained out through this corner of the promontory, the chalk covering became shaped into a broad and shallow valley some twenty miles across, with ridges to north and south, and opening out in a huge V towards the east. From these various inundations came further deposits of gravels and sands, and one, a tropical sea, left a thick layer of soft deposit down the centre of the valley, which would one day be known as London clay. These floodings and withdrawals also caused these later deposits to be formed into new, somewhat lesser ridges within the great chalk V.

Such was the place that was to be London, about a million years ago.

Of Man, there was still no sign. For a million years ago, although he walked upon two legs, his skull was still like that of an ape. And before he appeared, one great process had to begin.

The ice ages.

It was not the forming of frozen layers upon the Earth that altered the land, but their ending. Each time the ice began to melt, the ice-filled rivers began to churn and the stupendous glaciers, like slow-moving, geological bulldozers, gouged out valleys, stripped hills, and washed down the gravel that filled the riverbeds created by their waters.

In all the advances to date, the little north-western promontory of the great Eurasian landmass had been only partly covered by the ice. At its greatest extent, the ice wall ended just along the northern edge of the long chalk V. But when it did reach this far, about half a million years ago, it had one significant result.

At this time, a great river flowed eastwards from the centre of the promontory and passed some way to the north of the long chalk V. When the advancing ice began to block its way, however, thwarted, the cold, churning river waters sought another outlet, and about forty miles west of the place where the slate ridge lay, they burst through a weak point in the long chalk ridge, making that narrow defile known today as the Goring Gap, and flooded eastwards down the centre of the V that was so perfectly formed to receive them.

In this way the river was born.

Somewhere, during these later comings and goings of the ice, came Man. The dating is uncertain. Even after the river came through the Goring Gap, Neanderthal Man had still to develop. Not until the latest Ice Age, a little over a hundred thousand years ago, did Man as we know him evolve. At some time during the ice wall’s withdrawal, he moved into the valley.

Then, at last, somewhat less than ten thousand years ago, the waters from the dissolving Arctic ice-cap swept down, swamping the plain on the promontory’s eastern side. Cutting through the chalk ridges in a great J-shape, they washed right round the base of the promontory into a narrow channel running westwards to the Atlantic.

Thus, like some northern Noah’s Ark after the Flood, the little promontory became an island, free but forever at anchor, just off the coast of the great continent to which it had belonged. To the west, the Atlantic Ocean; to the east, the cold North Sea; along its southern edge, where the high chalk cliffs gazed across to the nearby continent, the narrow English Channel. And so, surrounded by these northern seas, began the island of Britain.

The great chalk V, therefore, no longer led to an eastern plain but to an open sea. Its long funnel became an estuary. On the estuary’s eastern side, the chalk ridges veered away northwards, leaving on their eastern flank a huge tract of low-lying forest and marsh. On the southern side, a long peninsula of high chalk ridges and fertile valleys jutted out some seventy miles to form the island’s south-eastern tip.

This estuary had one special feature. As the sea tide came in, it not only checked the outflow from the river, but actually reversed it, so that at high sea tide the waters ploughed up the narrowing funnel of the estuary and a considerable distance upriver too, building up a huge excess volume in the channel; as the sea tide ebbed, these waters flowed swiftly out again. The result was a strong tidal flow in the lower reaches of the river with a difference of well over ten feet between high- and low-water marks. It was a system that continued for many miles upstream.

Man was already there when this separation of the island occurred, and other men crossed the narrow, if dangerous, seas to the island in the millennia that followed. During this time human history effectively began.

54

BC

Fifty-four years before the birth of Christ, at the end of a cold, star-filled spring night, a crowd of two hundred people stood in a semicircle by the bank of the river and waited for the dawn.

Ten days had passed since the ominous news had come.

In front of them, at the water’s edge, was a smaller group of five figures. Silent and still, in their long grey robes they might have been taken for so many standing stones. These were the druids, and they were about to perform a ceremony which, it was hoped, would save the island and their world.

Amongst those gathered by the riverbank were three people, each of whom, whatever hopes or fears they may have had concerning the threat ahead, guarded a personal and terrible secret.

One was a boy, the second a woman, the third a very old man.

There were many sacred sites along the lengthy course of the river. But nowhere was the spirit of the great river so clearly present than at this quiet place.

Here, sea and river met. Downstream, in a series of huge loops, the ever widening flow passed through open marshland until, about ten miles away, it finally opened out into the long, eastward funnel of the estuary and out to the cold North Sea. Upstream, the river meandered delightfully between pleasant woods and lush, level meadows. But at this point, between two of the river’s great bends, lay a most gracious stretch of water, two and a half miles long, where the river flowed eastwards in a single, majestic sweep.