Let's Pretend This Never Happened (8 page)

Read Let's Pretend This Never Happened Online

Authors: Jenny Lawson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

Occasionally the turkeys would follow us, menacingly, on our quarter-mile walk to school, lurking behind us like improbable gang members or tiny, feathered rapists. Even at age nine I was painfully self-conscious, and was aware that dysfunctional pet turkeys would not be viewed as “cool,” so I would always duck inside the schoolhouse as quickly as possible and feign ignorance, conspicuously asking my classmates why the hell there were always jumbo quail on the playground. Then other students would point out that they were turkeys, and I’d shrug with indifference, saying, “Oh, are they? Well, I wouldn’t know about such things.” Then I’d slide into my seat and slouch over my desk, avoiding eye contact until the turkeys lost interest and wandered back home to shriek at my mother for their breakfast.

This worked perfectly until the morning when I ducked inside the school lobby a little too sluggishly, and Jenkins blithely followed me in, gobbling to himself and looking both clueless and vaguely threatening. Two other turkeys followed behind Jenkins. I quickly ran into my classroom as the turkeys wandered aimlessly into the library. I sighed in relief that no one had noticed the turkey expedition, until an hour later, when we all heard a lot of screaming and squawking, and we discovered that the principal and librarian had found the turkeys, who had somehow made their way to the cafeteria. They had also managed to

shit everywhere

. It was actually a little bit impressive, and also horribly revolting. The principal had seen the turkeys follow us to school before (as had most of my classmates, who’d just been too embarrassed for me to point out that they knew I was the turkey-magnet the whole time), so he called my father and demanded that he come to the school to clean up the mess that his turkeys had made. My father explained to the principal that he must be mistaken, because

he

was raising jumbo quail, but the principal wasn’t buying it.

A half-hour later, when my class lined up to go to PE, I found my father on his knees, cleaning up poop in the lobby. He was unsuccessfully attempting

to shoo the turkeys away, quietly but forcefully yelling, “GO HOME, JENKINS.” I froze and tried to blend into the wallpaper, but it was too late. Jenkins recognized me immediately and ran up to me, gobbling with excited recognition like, “OH MY GOD, ISN’T THIS AWESOME? WHO ARE YOUR FRIENDS?” and for the first time I didn’t run screaming from him. Instead I sighed and waved weakly, mumbling dejectedly, “Hey, Jenkins,” as my classmates stared at me in amazement. But not the

good

kind of amazement, like when your uncles show up at your school in a limo to invite you to live with them, and they’re Michael Jackson and John Stamos, but you never mentioned it before because you didn’t want to brag, and everyone feels really bad for not inviting you to their slumber parties when they had the chance. It was more of the

bad

kind of amazement. Like when you realize that not having the right kind of leg warmers is really small potatoes compared to being assaulted by an overexcited turkey named Jenkins, who is being scolded by your shit-covered father in front of your entire school. I think this was the point when I realized that I was kind of fucked when it came to ever becoming the most popular kid in the class, and so I just nodded to Jenkins and my father (both equally oblivious to the damage they’d done to my reputation), and I held my head up high as I walked down the hall and tried not to slip in the feces.

All the rest of that day I waited for the taunting to come, but it never did. Probably because no one even knew where to begin. Or possibly because they were intimidated by Jenkins, who I later heard had screamed threateningly at the kindergarteners as he was forcibly evicted from the premises. My sister tried to be blasé and pretended as if this sort of thing was commonplace. She refused to let it affect her social standing, and so it didn’t. This same confidence came in handy a few years later, when she was attacked by a pig on the playground. (That story’s in the next book. You should start saving up for it now.)

I, on the other hand, gave up completely at ever trying to fit in again.

When other girls had tea parties on the playground, I brought out my secondhand Ouija board and attempted to raise the dead. While my classmates

gave book reports on

The

Wind in the Willows

or

Charlotte’s Web

, I did mine on tattered, paperback copies of Stephen King novels that I’d borrowed from my grandmother. Instead of

Sweet Valley High

, I read books about zombies and vampires. Eventually, my third-grade teacher called my mother in to discuss her growing concerns over my behavior, and my mom nodded blithely, but failed to see what the problem was. When Mrs. Johnson handed her my recent book report on

Pet Sematary

, my mom wrinkled her forehead with concern and disapproval. “Oh, I see,” she said disappointedly, as she turned to me. “You spelled ‘cemetery’ wrong.” Then I explained that Stephen King had spelled it that way on purpose, and she nodded, saying, “Ah. Well,

good enough for me

.” My teacher seemed a bit flustered, but eventually the principal reminded her that my family had been the ones responsible for the

Great Turkey Shit-off of 1983

, and she seemed to realize that her intervention was futile, and gave up without feeling too guilty, because it was pretty obvious there was no way of turning me into a “normal” third-grader. And I felt relieved for her.

And actually? A little relieved for me too. Because it was the first time in my life that I gave myself permission to be me. I was still shy and self-conscious and terrified of people, but Jenkins had essentially freed me of the bonds of having to try to fit in. It was a lesson I should have been happy to learn at such a young age, if it weren’t for the fact that it was a teaching moment centering on a public turkey attack witnessed by all of the same kids that I would graduate from high school with.

Soon afterward, Jenkins and the other turkeys disappeared from our lives, but the lessons I learned from them still remain: Turkeys make terrible pets, you should never trust your father to identify poultry, and you should accept who you are,

flaws and all

, because if you try to be someone you aren’t, then eventually some turkey is going to shit all over your well-crafted façade, so you might as well save yourself the effort and enjoy your zombie books. And so I guess, in a way, I owe Jenkins a debt of gratitude, because (even if it was entirely unintentional) he was a brilliant teacher.

And also?

Totally delicious.

If You Need an Arm Condom, It Might Be Time to Reevaluate Some of Your Life Choices

(Alternative Title: High School Is Life’s Way of Giving You a Record Low to Judge the Rest of Your Life By)

I was the only Goth chick in a tiny agrarian high school. Students occasionally drove to school on their tractors. Most of my classes took place inside an ag barn. It was like if Jethro from

The Beverly Hillbillies

showed up in a Cure video, except just the opposite.

I purposely chose the Goth look to make people avoid me—since I was painfully shy—and I spent every free period and lunch hiding in the bathroom with a book until I finally graduated. It was totally shitty.

The end.

UPDATED:

My editor says that this is a terrible chapter, and that she doesn’t “even know what the hell an ag barn is.” Which is kind of weird. For

her

, I mean. “Ag barn” is short for “agriculture barn.” It’s the barn where they teach all the boll weevil eradication classes. I wish I were joking about that, but I’m totally not. You could also take classes in welding, animal husbandry, cotton judging and cultivation, and another class that I don’t remember the name of, but we learned how to build stools and fences in it. I’m fairly sure it was called “Stools and Fences 101.” None of this is made up.

UPDATED AGAIN:

My editor says this is still a terrible chapter and that I need to flesh it out more. I assume by “flesh it out” she means recover a bunch of awkward memories that I’ve invested a lot of time in repressing.

Fine.

My ag teacher told us that once, years ago, a student was hanging a cotton-judging banner on the ag barn wall when he fell off of the ladder and landed on a broomstick, which went

right up his rectum

. The idea must have really stuck with my teacher, because he was forever warning us to be constantly vigilant of any stray brooms in the area before getting on a ladder, and to this day I cannot see a ladder without checking to make sure there aren’t any brooms nearby. This is pretty much the only useful thing I ever learned in high school. Oh, and I also learned firsthand how to artificially inseminate a cow using a turkey baster (but that was less “useful” and more “traumatic,” both for me and the cow). This is what we had instead of geography. It’s also why I can never get the blue pie when I play Trivial Pursuit.

UPDATED AGAIN:

My editor hates me and is apparently working in collusion with my therapist, because they both insist that I delve deeper into my high school years.

Fine.

I blame them for this whole chapter. Please be aware that you’ll probably have horrible flashbacks of high school when you read this. You can forward your therapy bills to my editor.

Let’s start again. . . .

Pretty much everyone hates high school. It’s a measure of your humanity, I suspect. If you enjoyed high school, you were probably a psychopath or a cheerleader. Or possibly both. Those things aren’t mutually exclusive, you know. I’ve tried to block out the memory of my high school years, but no matter how hard you try to ignore it, it’s always with you, like an unwanted hitchhiker. Or herpes.

I assume.

Since I went to high school with all of the same kids who’d witnessed my peculiar childhood, I had already given up on the idea of becoming popular and perky, so instead I tried to reinvent myself with a Goth wardrobe, black lipstick, and a look that I hoped said, “You don’t want to get too close to me.

I’ve got dark, terrible secrets.

”

Unfortunately, the mysterious persona I tried to adopt was met with a kind of confused (and mildly pitying) skepticism, since the kids in my class were all

acutely

aware of all my dark, terrible secrets. Which is really not how secrets work at all. These were the same kids who’d witnessed the

Great Turkey Shit-off of 1983

, and who all vividly remembered the time my father sent me to our fourth-grade Thanksgiving play wearing war paint and bloody buffalo hides instead of the customary construction-paper pilgrim hats the rest of my class had made in art class. These were the same classmates who owned yearbooks documenting my mother’s decade-long infatuation with handmade prairie dresses and sunbonnets, an obsession that led to my sister and me spending much of the early eighties looking like the lesbian love children of Laura Ingalls and Holly Hobbie. I suspect that Marilyn Manson would have had similar problems being taken seriously as “dark and foreboding” if everyone in the world had seen him dressed as Little Miss

Hee Haw

in second grade.

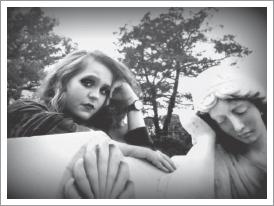

1980: It was a look that screamed, “Ask me about becoming a sister wife.”

My classmates refused to take me seriously, so I decided to pierce my

own nose using a fishhook, but it hurt too much to get it all the way through, so I gave up and then it got infected. So instead I wore a clip-on earring. In my nose. To school. It was larger than my nostril and I almost suffocated. Still, it was the first nose ring ever worn at my high school, and I wore it with a rebellious pride past the principal, who I’d expected would lock himself in his office immediately to stop the Twisted Sisteresque riots that would surely ensue at any moment from all the anarchy unleashed by my nose ring. The principal noticed, but seemed more bemused than concerned, and seemed to be trying to suppress laughter as he pointed it out to the lunch lady, who was bewildered.

And who was also my mother.

And

it was her clip-on.

My mom sighed inwardly, shook her head, and went back to slicing Jell-O. Neither of us ever mentioned the incident (or wore that earring) again.