Let's Pretend This Never Happened (44 page)

Read Let's Pretend This Never Happened Online

Authors: Jenny Lawson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

VICTOR

: True. I don’t remember ever having these conversations before we moved to the country.

ME

: Me either. Also, I just realized that I just went to a gas station in my pajamas to buy coffee. I just became a giant warning sign to others. I can’t decide whether this is a problem, or I’m just more comfortable here than I was in the city. Can it be both?

VICTOR

: I dunno.

What the hell happened to us?

ME

: [after a few seconds of silence] Growth?

VICTOR

: [nodding slowly]

Growth.

And Then I Snuck a Dead Cuban Alligator on an Airplane

November 2009:

He was my first. He was big, with a wide neck like an NFL player and a smile that said, “There you are! I’ve been looking for you everywhere.” Victor stared at me as if I had lost my mind, and pointed out that he was losing his hair and was missing several important teeth, but it didn’t matter.

I was in love.

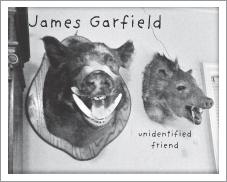

“Pay whatever it takes,” I said to Victor. “James Garfield WILL BE MINE.”

It was frightening, both for Victor and myself, this sudden lust I had to possess the dusty, taxidermied wild boar’s head hanging from the cracked wall of the estate sale we’d wandered into.

Victor refused to pay money for something he saw as hideous, but there was something in that toothy smile that screamed, “I AM SO DAMN HAPPY TO SEE YOU,” and when we left without him I was positively bereft. I spent the next week looking at the blank spot on the wall where James Garfield would have smiled at me. Whenever Victor would try to cheer me up with a joke or with videos of people hurting themselves, I would force myself to smile and then sigh, saying, “James Garfield would have loved that.”

Eventually the melancholy got too strong and Victor angrily gave up and drove me back to the estate sale, where he was totally unsurprised to find that James Garfield had not been sold. He’d made me stay in the car, because he said my look of intense longing would affect his ability to negotiate, and offered the guy in charge of the sale twenty-five dollars for him. The man sneered and said that he could just rip out the tusks and sell them on eBay for that, and Victor came back to the car to tell me how negotiations had broken down.

“THEY’RE GOING TO DISMEMBER JAMES GARFIELD?”

I screamed. “STOP THEM. PAY ANYTHING.

HE IS A MEMBER OF OUR FAMILY

.” Victor stared at me in bafflement. “I’d do it for you,” I explained. “I’d pay the terrorists anything to get you back.” Victor sighed and laid his head on the steering wheel.

A tense twenty minutes later he came back to the car, lugging the beautiful head of James Garfield like some kinda goddamn American hero. I cried a little, and Hailey clapped her tiny hands in delight. “You will be my best friend,” she said to him as she petted his snout.

Victor looked at both of us like we were mad, and then stared straight ahead as he made me swear this would not be the start of some sort of wild-boar-head collection. “You’re being ridiculous,” I said. “James Garfield is one of a kind.”

When my parents came to visit a few weeks later, my mother shook her head in bewilderment. I’d expected my father to feel at least slightly vindicated that his love of taxidermy hadn’t skipped a generation after all, but he seemed just as baffled as Victor. He peered quizzically at the mangy fur

shedding from James Garfield, and told me he could make me a much nicer boar head, if that was what I was into. “No,” I said. “This is it.” I was not a fan of taxidermy and never would be. Having one dead animal in the house is eclectic and artistic. More than one reeks of serial killer. There really is a fine line there.

APRIL 2010:

Half of a squirrel arrived in the mail today. It was the front part, almost down to the belly button, and it was mounted on a tiny wooden plaque.

It was odd. Both because I was not expecting any squirrel parts, and because the squirrel was dressed in full cowboy regalia. He was holding a tiny pistol out, threateningly trained at the viewer (presumably to defend the miniature marked cards in his other tiny hand), and his eyes followed you from room to room, like one of those 3-D pictures of Jesus from the seventies.

“Hey, Victor?”

I yelled from the living room.

“Did you buy me a half of a squirrel?”

Victor walked out of his office and stopped short as he stared at the tiny bandito pointing a gun at him.

“What have you done?”

he asked.

“Ruined Christmas?” I guessed. I found it hard to feel guilty about ruining his surprise, though, since the box

was

addressed to me, but then I saw the note on the package and realized it was actually from a girl who read my blog, and who had agreed that Victor was totally in the wrong last month when he’d refused to buy me the taxidermied squirrel paddling a canoe

1

that I’d found in an antique shop.

“Oh, never mind,” I said. “Apparently this half squirrel is a present from someone

who understands fine art

.”

“You can’t possibly be serious.”

“It would be rude NOT to hang it up,” I explained to Victor. “I will name him Grover Cleveland.” Victor stared at me, wondering how his life choices had taken him here.

“Didn’t you once tell me that more than one dead animal in the house borders on serial-killer territory?” he asked.

“Yes, but this one is wearing a hat,” I explained drily. He couldn’t argue with that kind of logic. No one could.

JANUARY 2011:

“I am a moderately successful writer, and if I want to buy an ethically taxidermied mouse I should not have to justify it to anyone.”

This was what I was screaming as Victor glared at me, dripping rain water all over our foyer. In truth, we weren’t really arguing about whether I was

allowed

to spend money. We were arguing about the fact that the taxidermied mouse I’d bought had been lost. The delivery website said it was left on the porch, but it was nowhere to be seen. I suspected burglars, but even imagining the small compensation of their mystified faces as they opened the box containing a dead mouse wasn’t enough to make me feel less upset. Then I’d noticed that the tracking page had transposed my street number, and so I sent Victor out into the dark and rainy night to go find the neighbor who was probably very confused about who had mailed him a dead mouse. Victor had been a bit flabbergasted at my request, but after yelling for a bit about . . .

I don’t know; I wasn’t really paying attention. Budgets, maybe? . . .

he finally threw on a coat and went out in search of the mouse. He returned twenty minutes later and told me that the address didn’t even exist, and that he’d asked the people at the houses near where the address would have been and none of them had seen any packages. He was wet and frustrated, and I assumed that accounted for how

irrational he was being as I pushed him back out the door to check with all the neighbors on the block.

“You didn’t even tell me you’d bought a taxidermied mouse,”

Victor yelled, and I said, “Because you were asleep when I found it online, and it was so cheap I knew it would be gone if I didn’t buy it immediately. I didn’t want to tiptoe into our bedroom at three a.m. to whisper,

‘Hey, honey? I got a great deal on a stuffed mouse that died of natural causes. Can I have your credit card number?’

because that would be CRAZY. And that’s why I used

my

credit card.

Because I respect your sleep patterns.

But then I forgot to tell you about it, because I bought it at three a.m., when I was drunk and vulnerable. Just like

you

with all those choppers you keep buying on infomercials. Except that this is better, because I’ll actually

use

a taxidermied mouse. That is, I

would have

. . . until—

crap

—until he went missing,” I ended in a whisper.

“Are you . . . are you

crying

?” Victor asked, stunned.

I wiped at my eyes. “A little. I just hate to think of him out there in the rain. All alone.” My voice trembled, and Victor closed his eyes. And rubbed his temples. And sighed deeply before staring at me and walking back out into the rain. Forty minutes later he walked in with a tiny wet box and a look that said, “I will disable your computer when I go to bed from now on.” But I rushed up and gave him a dozen kisses, which he gruffly accepted as he dried off with the towel I handed him.

“It was at the abandoned house at the end of the block,” he said. “Apparently someone just dumped everything that didn’t have a proper address there. There must’ve been twenty-five packages lying on that porch.”

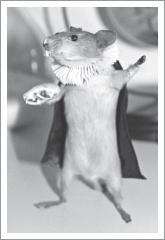

But I wasn’t paying attention, as I was too busy pulling Hamlet von Schnitzel from his watertight baggie.

“What.

The fuck.

Is

that

?” Victor asked.

It was pretty obvious what it was. It was a mouse dressed as Hamlet. His Shakespearean ruff collar held up his wee velvet cape, and he seemed to be addressing the bleached mouse skull held nobly in his tiny paw. I held it up to Victor, squeaking, “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him well.”

Victor looked at me worriedly.

“You have a problem.”

“I

DON’T

HAVE A PROBLEM.”

“That’s exactly what people with problems say. Denial is the first sign of having a problem.”

“It’s also the first sign of

not

having a problem,” I countered.

“I’m pretty sure defensiveness is the second sign.”

I placed Hamlet von Schnitzel in a glass bell jar to protect his little ears from Victor’s hurtful accusations. But I had to admit that I didn’t completely understand my recent obsession with odd taxidermy either. It worried me. I still didn’t understand my father’s fascination with dead animals, and I refused to buy any that weren’t terribly old or didn’t die of natural causes. I still shooed spiders and geckos out of the house with a magazine and a helpful suggestion of “Perhaps you’d like some fresh air.” I considered myself an animal lover, donated to shelters, and never wore real fur, but it clashed with the other side of my personality, which was continually browsing through shops, always on the lookout for beavers in prairie dresses, or a diorama of the Last Supper made entirely with otters. Victor was right: I needed to stop. I told myself that I was finished and I vowed that I would not end up like my father, surrounded by the soulless, unblinking eyes of dead things. And with a little willpower I vowed to conquer my curious and terrible obsession.

APRIL 2011:

I just bought a fifty-year-old Cuban alligator dressed as a pirate.

This is

so

not my fault. Victor broke his arm by falling down some stairs in Mexico, so I went with him on a business trip to North Carolina so I could help him. The trip was uneventful, until we stopped at a little shop

on the way to the airport. While Victor went to use the restroom, I stumbled upon the small, badly aged baby alligator, which was fully dressed and standing on his hind legs. He was wearing a moth-eaten felt outfit, a beret and a belt. He was missing one hand, and he was nineteen dollars. His tiny belt hung sadly, and I appreciated the irony of an alligator wearing a belt that was not made of alligator. His mouth was open in a wide grin, as if he’d been waiting for me for a very long time. I remembered my vow to not buy any more taxidermied animals and feverishly searched for loopholes while Victor looked through the aisles for me. I contemplated stapling a strap to the alligator’s shoulders, putting my lipstick in his mouth, and calling him an alligator purse, but it was too late.

He had me at the beret.