Kerry Girls (8 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

Facsimile of

The Colonist

. (Sydney, NSW: 1835–1840), 22 September 1840.

Initially efforts were made through the English Parliament and through newspapers there to try and ‘sell’ Australia as a desirable place to emigrate to, stressing the opportunities available there for people willing to work. However, it was a hard sell, with the prevalent view of the country as primarily a penal settlement.

At this particular time, Caroline Chisholm came to the fore. Mrs Chisholm was born in England, the daughter of a well-to-do farmer, and had been reared in the tradition of evangelical philanthropy.

5

She married, at 22, Captain Archibold Chisholm, a Catholic, and she later converted to Catholicism herself. Caroline accompanied her husband to India initially where he served in the East India Company. During their time there, they lived in Madras, where Caroline founded the Female School of Industry for the Daughters of European Soldiers. Following Captain Chisholm’s posting to Sydney, Caroline immediately saw the problems facing the assisted female immigrants who remained in Sydney without employment or shelter and for whom the government had made no provision. Mrs Chisholm took it on herself to meet with the immigrant ships as they arrived; she found jobs for the girls and sheltered many of them in her own home. She lobbied Governor Gipps and Lady Gipps to provide a ‘Female Emigrants’ Home’. Despite discouragement and anti-Catholic feeling, she was eventually granted use of an old immigration barracks, keeping up to ninety women here at a time.

She then set out into the bush to the sheep and cattle stations with ‘successive batches of Irish girls, placing them mainly as domestic servants in the homes of farmers of good character’.

6

By the time of her first report –

Female Immigration, Considered in a Brief Account of the Sydney Immigrants’ Home

(Sydney, 1842) – she was able to announce the closure of the Female Emigrants’ Home, as her policy for distributing female immigrants into the country areas had been so successful.

7

While there was still distrust of her motives and some criticism, the

Australasian Chronicle

, of Tuesday 12 August 1842 had to admit ‘the value of Mrs Chisholm’s philanthropic exertions, to which it is impossible to assign too much praise’.

8

On the other side of the coin was John Dunmore Lang, a Presbyterian minister who had arrived in Sydney from Scotland in 1823. From his earliest days in New South Wales, Lang was a divisive and troublesome figure who made immediate enemies of both Anglicans and Catholics. He achieved initial notoriety by fighting with the governor Sir Ralph Darling over the provision of a dedicated Presbyterian college in the capital. On a visit back to England in 1830, he persuaded the Colonial Office to advance £3,500 for the establishment of a college in Sydney and to improve what he saw as the low moral tone of Australian society. He recruited and arranged for 140 Scottish workers and their families to emigrate to New South Wales. He arranged with them to repay their fares over a period, once they had started working. Lang was a bigoted but able leader of his flock. He established three newspapers in Australia, which were published up to 1851 and which he used to publicise his views and condemn those whom he saw as his enemies. ‘He attacked fancy dress balls, Sabbath picnicking and alcoholic intemperance’.

9

He saw the colony as a dissolute, debauched place, filled with sexual and alcoholic immorality, and he blamed convict transportation for this. It didn’t take him long to associate most of the convict transportation with Irish convicts. While Lang was not the only critic of the Irish he was one of the loudest. The

Sydney Morning Herald

took a powerful and bitter anti-convict stance and in that stand they laid most of the censure on Irish convicts rather than English. An example of this extreme racist attitude was evident in an article in

The Australian

on the 13 April 1846 when ‘rating’ the merits of labourers, placing a lowland Scotch or English labourer as equal to ‘seven Irish or highlanders and to ten coolies’.

With the colonisation of the interior new areas were opening up all the time, leading to the demand for more immigrants, but by this time there was an increasing emphasis on females. While there was an urgent need for more labourers, farmhands and shepherds in the bush, there was also rapid development in the new urban settlements of Port Philip (Melbourne), South Australia (Adelaide) as well as Sydney in New South Wales. It was reckoned that by 1841, 80 per cent of the interior was populated by males. This situation had led, in aboriginal areas, to white men and ‘gin women’ cohabiting freely. Indeed we have an example of this in the epic story

Kings in Grass Castles

10

in which Dame Mary Durack tells of her pioneering Irish family who built a cattle empire in Western Australia. Drovers, cattle and sheep herders who lived out in isolated areas of the bush for months on end were ‘glad enough of the dusky companions whose only terms were the right to live and to serve’.

11

Mixed-race babies resulting from these liaisons were regarded with hostility, often leading to abandonment and/or killing and in a later generation to the ‘Stolen Children’ experience. Religious and civil leaders came to the conclusion that the only solution to the problem was the introduction through immigration of a large supply of white women. This immigration initiative would solve two problems for the colonial administration. The women would initially be servants to the up and coming city bourgeoisie and to the country landowners who had been granted vast properties and who needed women to cook for their families and workers, to milk, feed farm animals, look after dairying and to mind their children. If these women were single they would then also be available for marriage to settlers, some free settlers and also a growing number of Ticket of Leave men who had served their sentences and were no longer looked down on as convicts.

Mrs Chisholm, with her husband, was back in England in 1847 and in giving evidence before a British Parliamentary Committee explained that, from her own experience, there was a pressing necessity not just to remedy the labour shortage in the colony but also an urgent need for women who would marry settlers. Armed with hundreds of petitions from New South Wales settlers, she demonstrated the need for both wives and workers. She also lobbied for reform of migration policy, including shipboard conditions for migrants. With her previous experience of settling girls by shrewd placement and by dispersing them individually to the outback, she recommended a similar approach to the reception of all female immigrants. However, she did not mention workhouses or indeed orphanages in this regard. John Dunmore Lang immediately responded with sectarian attacks on Mrs Chisholm, accusing her of promoting ‘Popery’ in the colony.

Mary Kennedy

Mary Kennedy was in Dingle Workhouse when she was selected to travel on the Earl Grey Scheme to Australia. On arrival, she declared her age as 17, her religion as Roman Catholic, and that her parents were Daniel and Debby (father living in Dingle, Kerry). Her descendants believe that Mary was baptised in Aunascaul on 28 February 1833 and her parents were Daniel Kennedy and Gobnet Keller [

si

c

]. Mary would have had Irish as her first and possibly only language.

Ian Mac Andrews, great-great-grandson of Mary, takes up the story:

Mary left with the other Dingle girls from Plymouth on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

on 28 October 1849 and arrived in Port Jackson on 3 February 1850. Mary was also one of the luckier ‘orphan’ emigrants, in that her voyage with the other girls from Dingle, Listowel, Ennis, Galway, Loughrea, Ennistymon, Dublin and Scariff was overseen by the humane and caring Surgeon Superintendent Charles Strutt. On arrival, after spending some weeks in the depot in Sydney, she was sent onwards, travelling on the

Eagle

to Moreton Bay. Mary was initially indentured with James Cook of Ipswich and was employed later as a housemaid by John McIntyre of Ipswich, a storekeeper, at £6–£8 per year. Two years later, on 28 July 1853, she married William Samuels at Drayton Parsonage, Aubingy, then part of New South Wales, now in the State of Queensland.

I believe that Mary & William must have been some of the original settlers on the Darling Downs in Queensland at Drayton Swamp based on the fact that Mary was a Roman Catholic but they were married in the Drayton Parsonage (Church of England) as there was no RC church at that time & not even a Church of England church, just a parsonage. Both Mary and William signed the marriage certificate with an X.

William Samuels went to work for William Horton, who had arrived in Australia in 1832 as a convicted felon. Horton had been transported for stealing a coat. A free man from 1839, he worked initially as a stockman which took him north from the Hunter Valley in 1840 to a station at the Severn River, just south of the Queensland border. Here, Horton met early pastoralists including those who were the first to explore the Darling Downs. He was later at publican and businessman in Drayton, building the Royal Bull’s Head Inn there in 1847. The slab-built inn with shingled roof, served as an important meeting place for the squatters.

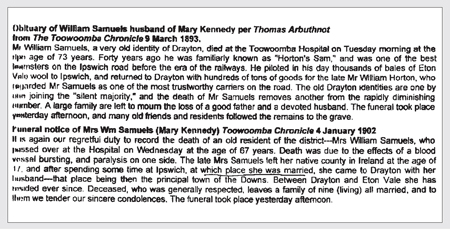

The obituary and funeral notice of Mary and William Samuels,

Queenslander

,

18 March 1893.

The marriage of Mary Kennedy and William Samuels, Drayton, 28 July 1853.

The inn was large and well equipped with a parlour and all the requirements for a constant stream of visitors, including travellers, clergymen, settlers and anyone travelling to the area from the coast.

In 1848 the Revd Benjamin Glennie conducted the first Church of England service on the Darling Downs at the Royal Bull’s Head Inn and it was this clergyman who married Mary and William in 1853. ‘Glennie’s parish was the whole of the Moreton Bay (Brisbane) and the Darling Downs. According to his first Australian Diary, he travelled 1300 hundred miles in one year.’

12

From this time on the Samuels family lived at Drayton and we know from William’s obituary that he worked as a teamster on the Ipswich road, before the era of the railways, for Samuel Horton, taking wool to Ipswich and returning with much needed supplies for the ever-expanding number of Queensland settlers and squatters. These pioneer squatters and settlers were exposed to dangers and hardship that William and Mary would have shared in. Over the next twenty-one years, Mary had twelve children and only one of these appears to have died in infancy. This was an almost miraculous occurrence in an era of such extreme living conditions. Mary would have had complete responsibility for rearing, feeding and educating her large family while William was on the road. It would have been a lonely existence without schools, doctors or churches. She would have had to nurse her sick children herself, help other women to do the same, combat the heat, dust, drought and dangerous wildlife, together with the normal daily back breaking work.

Mary outlived William by nine years and died when she was sixty-nine years old. Nine of her children survived her; Sarah (d. 1861), Ellen (d. 1866) and William (d. 1896) were dead by this time.

In Australia, the newly arrived governor of New South Wales, Sir Charles Augustus Fitzroy, set to rectifying the situation. Governor Robe of South Australia suggested that part of the South Australian Land Fund be used to attract emigrants. Sir Daniel Copper, the Speaker of the New South Wales Legislature, also wrote to Thomas Spring-Rice, Lord Monteagle, the Irish Peer, ‘We wish to receive emigrants; we are willing to pay for them. There are millions among you dying of hunger, let us have those starving crowds; here they will find a superabundance of the necessaries of life.’

13

In Ireland, the extent of the Famine from 1845 onwards, with hundreds arriving daily to the workhouse doors, was putting extreme pressure on the individual Boards of Guardians to provide food and shelter for the rapidly growing numbers of these destitute families. Children usually made up about half of the workhouse population. These children and young people were either orphans whose parents had died, or who had been left at the workhouse by one parent unable to provide and who would have intended to return for them at a future date. Public funds and local taxes were being exhausted by the level of expenditure required to keep the system afloat. Furthermore, there was very little possibility of any of these young people getting work, enabling them to leave the workhouse, and this applied in particular to the girls.