John Aubrey: My Own Life (49 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

My friend Mr Paschall

45

tells me the Quakers do all they can in town and county to make a great show. He believes the active ruling men among them were principals in the rebellion, and owe their lives to a scarce-hoped-for mercy from the King. He fears that the Republicans who were at the bottom of the rebellion may be exerting a mischievous influence for the overthrow of the monarchy and that their joy over the indulgence is due to their hopes of overthrowing the Church of England with the help of the Roman Catholics.

Robert Barclay’s book

46

,

System of the Quakers’ Doctrine in Latin

, first appeared in English in 1678, dedicated to King Charles, now to King James. Barclay is an old, learned man, mightily valued by the Quakers. His book is common.

. . .

6 July

Today at the Royal Society

47

we discussed the plant called Star of the Earth, which grows plentifully about the mills near Newmarket and Thetford. I explained that it can also be found at Broad Chalke.

. . .

Mr Dugdale has criticised

48

me for putting hearsays into writing. For example: when I was a schoolboy in Blandford there was a tradition among the country people of Dorset that Cardinal Morton – Bishop of Ely, then Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Henry VII – was the son of a shoemaker of Bere Regis. Mr Dugdale believes such things should not be part of a written life. But if I do not collect these minute details, they will be lost for ever. I do not say they are necessarily true, only that they have been believed true and have become part of local traditions.

I am setting out now on an excursion to Yorkshire.

. . .

On a rocky mountain

49

above Netherdale there is a kind of moss that also grows in Scotland. I have pressed a piece of it, together with its roots, between two sheets of paper.

. . .

September

In Yorkshire

50

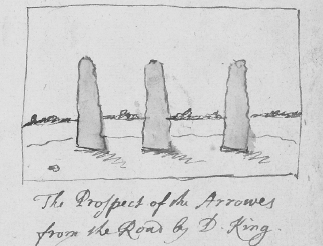

I have seen the pyramid stones called the Devil’s Arrows today, near Borough-Bridge, on the west side of the Fosse Way. They are a kind of ragstone and not much weather beaten. I did not have the right idea about this antiquity until I saw it for myself. The stones stand almost in a straight line except the one near the Three Greyhounds, which is about two and a half yards out of line with the rest. I could not see any sign of a circular trench around the monument, like that at Avebury or Stonehenge.

The crosses at Borough-Bridge and nearby villages are the highest I have ever seen. I think the early Christians must have re-used the stone from these Devil’s Arrows to save themselves the trouble of drawing new stones out of the quarries to make their crosses. This would have reduced the number of the Devil’s Arrows still in place.

In this county

51

, the women still kneel on the bare ground to hail the new moon every month. The moon has a greater influence on women than on men.

From Stamford to the bishopric I saw not one elm on the roads, whereas from London to Stamford there are elms in almost every hedge.

. . .

Sir Charles Snell

52

has sent me my poor brother Thomas’s ill-starred horoscope, which he had refrained from sending until now lest dread of the event might have killed him. But since poor Thomas died in 1681, no harm can come of it now.

. . .

October

This month I have dipped my fingers in ink. I am transcribing all the British place names I can find in Sir Henry Spelman’s

Villare Anglicanum

(printed in 1656) and interpreting them with the help of Dr Davies’s Dictionary and some of my Welsh friends. Spelman’s book was made from Speed’s maps, but in the maps many names are false written, so Spelman has transcribed them wrongly in his book, and in addition there are some errors introduced by the printer. I began reading Spelman’s book with only the intention of picking out the small remnant of British words that escaped the fury of the Saxon conquest. But then I decided to list the hard and obsolete Saxon words too and interpret them with the help of Whelock’s Saxon Dictionary. We need to make allowances for these etymologies. There were, no doubt, several dialects in Britain, as we see there are now in England: they did not speak alike all over this great isle.

Following my Natural History

53

of Wiltshire, I am tempted to write memoirs of the same kind for Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Flintshire and Surrey. I am fearful of what will happen to my work if I die. What shall I say or do with these pretty collections? I had thought to make Mr Hooke my executor to publish them after my death, but he has so much of his own work to do that he will not be able to finish mine. I think Mr Wood would take more care than anyone else, but many of the remarks I have collected will be lost if I do not stitch them together myself.

. . .

16 December

On this day

54

Sir William Petty died of a gangrenous foot caused by gout at his house in Piccadilly Street opposite St James’s Church. As soon as I can, I must visit his house and take note of the manuscripts he has in his closet. His last two printed tracts were comparisons of London and Paris. I expect to find much unprinted or unfinished work.

. . .

I have been chosen

55

to serve again on the committee that audits the Royal Society’s accounts.

. . .

I am grateful to Mr Wood for remembering my great-grandfather, Dr William Aubrey, in his book. I am grateful too to his brother, who entertains me so well when I am in Oxford.

. . .

Anno 1688

10 June

On this day King James’s son was born. He will surely be raised a Roman Catholic and succeed to the English throne ahead of his Protestant half-sister Mary, wife of William, Prince of Orange. Anti-Catholic sentiment has reached a climax and many talk of inviting Mary and William to England. It is not clear what this might achieve. Perhaps their presence would help overturn some of the King’s policies, or perhaps there could be some kind of regency.

. . .

12 June

I dined this evening

56

at the Mermaid Tavern with Mr Wood and Dr Plot. He told Mr Wood that when his book is published, he would give him 5 li. for a copy. I have asked Mr Wood to give all the papers of mine that he has to the museum for safe keeping.

. . .

I have decided

57

to donate to the museum in Oxford a miniature of myself by Samuel Cooper, and one of Archbishop Bancroft by Nicolas Hilliard, the famous illuminer in Queen Elizabeth’s time, together with a collection of thirty-seven coins (seven silver, the rest brass) and other things of antiquity dug up from the earth. The picture of me is done in water colour and set in a square ebony frame; that of Archbishop Bancroft is set in a round box of ivory, not much bigger than a crown piece. I have sent all these things to Mr Wood in Oxford and asked him to deliver them for me. I promised him he could peruse all that I am giving first, before passing the box and its contents to the museum.

. . .

May, June

58

, and July this year have been very sickly and feverish.

. . .

October

Dr Plot complains that Mr Wood has not yet delivered my box to the museum. He has let the museum have the two miniatures and the coins I sent, but kept back the rest together with the manuscripts of mine that are in his keeping.

. . .

New troubles arise upon me like hydras’ heads.

I am concerned

59

about my papers and collections, which are still with Mr Wood. He will not surrender them to Dr Plot for the museum as I have asked. Dr Plot has told Mr Ashmole what has happened and he is outrageously angry, as Mr Wood is suspected of being a Papist, and in these tumultuous times his papers will surely be searched. My manuscripts must not fly around like butterflies.

My brother William, whom I have injured, is very violent. In our shared troubles over money, I have not always behaved well and have put my interests above his when I needed to. In my father’s will he was left a portion but it was always hard for me to pay it and lately impossible. He is keen to meet me, but I must avoid him. He writes to me often, sending his letters to me via Mr Hooke. This strife between us gravely disturbs me.

My heart is almost broke and I have much ado to keep my poor spirits up. I pray God will comfort me.

I am separated from my books. They are all at Mr Hooke’s or my old landlord Mr Kent’s, so even if I had any leisure to enjoy them, I could not.

To divert myself since the removal of my books, I have been perusing Ovid’s works. I have picked up a sheet or so of references for my Remaines of Gentilisme (my collection of folklore which I have been working on since February last year); some of them are from his

Epistles

and

Amores

, where one would not expect to find anything. See what a strange distracted way of studying the Fates have given me.

To rescue my finances, I need to sell my last remaining interest in Broad Chalke farm and keep an annuity of 250 li. for myself if I can. My brother William must not hear of it.

I desire of God

60

Almighty nothing but for the public good.

My time is running out.

PART XIV

Transcriptions

Anno 1688

5 November

ON THIS DAY

William, Prince of Orange, landed at Torbay with an army. He has been formally invited to England by a small group. They are:

The Earl of Danby

The Earl of Shrewsbury

The Earl of Devonshire

The Viscount Lumley

The Bishop of London

The Earl of Orford

The Earl of Romney

. . .

Here in London the rabble has demolished Popish chapels and the houses of several Popish lords, including Wild House, the residence of the Spanish ambassador. They pillaged and burnt his library. I am afraid the unrest will spread to Oxford and Mr Wood’s papers, many of my own among them, will be searched and destroyed, as the whole University believes him to be a Papist.

. . .

18 December

On this day William, Prince of Orange, reached London.

. . .

I went to see

1

Mr Ashmole last Tuesday; he is very ill. He told me Mr Wood is still refusing to send my box of papers to the museum for safe keeping, but if he does not do so without further delay he will no longer look on him as a friend and will not give another farthing to the University. Mr Wood is suspected of being a Roman Catholic and my papers will not be safe with him if (or when) his own are searched and burnt. Mr Ashmole says much more care is taken now at the museum and books are safer there than they are even in the Bodleian Library. He suggests that the papers I desire kept secret should be sealed up in a locked box in the museum and not opened until after my death. I think his advice very solid and sedate: there are some things in my Lives that make me open to scandal, and I have written a letter or two which I wish were turned to ashes!

My shirt, cap and cravat are with my laundress Mrs Seacole in Oxford: I hope she keeps them safe. I was meant to pick them up from her within a fortnight, but the times prevent me going back to Oxford at the moment. I wish I could go next month, or in February, but I fear I will need to be in hiding then from my brother and other creditors.