Indian Captive (4 page)

The trail wound in and out among rough, jagged tree stumps. The borrowed horse slowed down from a trot to a walk. His hoofs beat gently on the soft dirt trail. Molly bent her head, pressing her nose into the horse’s mane, as an overhanging branch scraped her shoulders. She straightened her back again.

Then suddenly the horse stopped. He stood still, his whole body quivering. Molly’s song died on her lips. Her face turned pale. She leaned forward and gave the horse a pat. The sharp, sweet tones of a bird song rang out through the quiet. A fallen branch crackled beneath the horse’s feet, as he stirred nervously. Then all was still.

Underneath the oaks it was black and dark. Molly stared into the blackness. The trunks of many trees crowded close and seemed to press upon her. Was something moving there? Her breath came short, as her happiness faded away. The forest had changed from a world of beauty to a world of fear.

The girl glanced back quickly over her shoulder, as if a glimpse of the Dixon home, which she had so recently left, might give her comfort. Here, between the reality of the neighbor’s log cabin and the unreality of the unknown dark forest she paused, sensing danger. Here anything might happen. Here wild animals prowled, Indians hid, and evil lurked.

Molly went white about her lips. She turned her head and looked on all sides. She saw no movement, heard no sound. The sharp, strident bird song rang out again, piercing in its sweetness. Was it a note of warning or a word of comfort?

Then strangely, a vision of her home rose before the girl’s eyes. She saw her tall, lanky father in the big kitchen with her mother—and her mother was scared as she had been last night, as she always was when there was talk of Indians. Molly pulled on the horses bridle and urged him forward. Keeping her eyes on the trail ahead, she rode on, faster and faster, as fast as the trail would permit. She was fearful now—not for herself, but for her family. What if the Indians had come in her absence?

It was sun-up when she came out of the forest and entered the clearing. She circled the barnyard slowly, staring at the unchinked log out-buildings as if she had never seen them before. She saw her two older brothers grinding a knife at the grindstone; her father shaving an axe-helve at the side of the house. She rode up close to the cabin and bent her head to look in through the torn paper of the kitchen window. She let herself stiffly down on the door-log.

A scene of bright happiness confronted her. Everything was just as she had left it. Mrs. Wheelock was dressing her children in the corner. Her mother and Betsey were starting breakfast. Nothing had happened. The world was a beautiful place after all, and all her fears were groundless.

Neighbor Wheelock came out of the house, stamping on the door-log.

“There, gal! Let me have that horse!” he cried, taking the bridle from Molly’s hand. “Mine’s sick—no better this morning. Got to go back to my house to fetch a bag of grain I left there.”

“Better wait till after breakfast, Chet!” called Molly’s mother from within. Her voice sounded cheerful as if her fear were gone.

“I’ll be back ’fore the corn-pone’s browned on one side, Mis’ Jemison,” replied Wheelock, with a laugh.

“Take your gun along then,” called Thomas from beside the cabin. “Might be you’d meet some of them Injuns you was a-tellin’ us about. Might be they’d git a hankerin’ for your scalp!”

“Don’t know but I will…” Wheelock disappeared inside, then came out, gun in hand. “It’s not the Injuns so much,” he answered. “They ain’t come this fur

yet.

But I might pick up a wild turkey for the women-folks to cook. With all this big family to feed, they’ll need all the game they can get.” He mounted the borrowed horse and rode away.

Molly entered the cabin and closed the door behind her.

The window paper, once slick with bear’s grease, had split from drying. The morning sun came through the torn openings and brightened the dim interior. It rested on the tousled quilts on two large beds at the end of the room, on the great spinning-wheel and the small, on the home-made loom in the corner. It lingered on the somber homespun and soft deerskin clothing hung from wooden pegs in the wall. It made spotty patches on the uneven puncheon floor. It was traveling toward the fireplace where the corn-pone lay tilted up on a board. Soon the light of the sun would mingle with the shooting gleams of fire.

Molly stood motionless, watching. Then, out of the corner of her eye, she was suddenly conscious of her mother’s actions. Time seemed to stand still as she waited. She saw her mother walk across the room, carrying a stack of wooden trenchers toward the slab table. She saw her mother open her lips, as if about to speak. She knew what she would say before the words came. She had heard them often enough before: “Stop your dreamin’, Molly, and git to work!” But this time the words were never said.

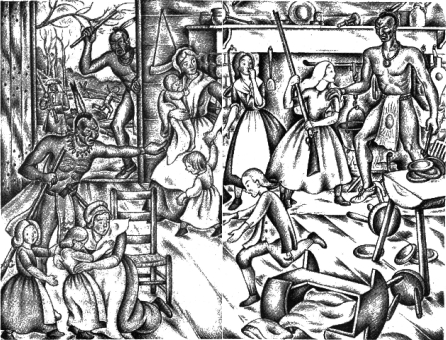

The room was very quiet and the words were never said. For, through the stillness, a volley of shots rang out, and fear, turmoil and shock came that moment on all. Molly, still standing where she was, saw her mother drop the trenchers and snatch the baby from its cradle. She heard her mother’s words: “God help us, they’ve come, just as Chet said!” She heard nine-year-old Davy Wheelock cry, “Indians! It’s the Indians!” She saw Davy’s mother sink limply in a chair, fainting, then rally and gather her children together and start a piteous wailing. She watched Betsey as the white-faced girl bent over the fire mechanically and turned the corn-pone, to keep it from burning. She watched it all, for her feet refused to move.

Then everything happened at once.

The door, the heavy battened oak door, built to keep the Indians out, opened to let them in. The morning sun shone on them, too, and made their skins shine like flashing copper. Above the noise and din which came with them, the baby’s crying could be heard.

Out through the door, open now, Molly saw a scene she was never to forget. A man and horse lay dead beside the well-sweep. She wondered who it was. It couldn’t be Neighbor Wheelock, who had gone laughing from the house so short a time ago. No, it couldn’t be. He was safe, back at his house on Sharp’s Run, fetching a bag of grain he’d left behind. He was far away, safe. There was not time enough for him to go home and be back again so soon. But there, there on the ground, lay his coon-skin cap with the striped tail a-dangling. There at his side lay a horse—a horse of the same color as Neighbor Dixon’s horse. Was it only this morning she rode him through the woods?

Molly covered her eyes so she should not see. But the sounds, these she could not shut out—the shouts and whoops of the Indians, the cries and moans of Mrs. Wheelock and her mother, of Betsey and the little ones. She wondered vaguely where her father was and where the boys had gone and why they did not come to help.

Then she saw her father’s long rifle hanging on pegs above the fireplace. Had everybody forgotten it? She rushed over, climbed a stool and took it down. Some one must help. She would do it herself. Then, as quickly, a heavy hand was laid on her shoulder; the gun was jerked from her grasp and looking down, she saw that the corn-pone was burnt to a crisp.

The next moment she was in the bright sun, out in front of the cabin, weeping about the corn-pone which should have been their breakfast. They were all there with her, the two women and all the children. She turned away from the well-sweep and it was then that she saw her father. He was standing still, making not the slightest struggle, while two Indians bound him round with thongs. She wondered where the boys were. She looked toward the grindstone, but they were gone. Had they run away in time? She watched the Indians rush through the cabin, overturning chairs and tables, breaking and destroying; she saw them bring things out—bread, meal, and meat. Was this what was called plundering? Had the time, the dreaded time, of which she had heard so much, come at last?

They all stood together, huddled in a pack, waiting. Soon the Indians left the house and crowded round. The glaring, painted faces came up close and Molly’s heart almost stopped beating. Though none but her father was bound, she realized now for the first time that they were prisoners. Then she saw that with the Indians there were white men, dressed in blue cloth with lace ruffles at their sleeves, speaking French in hurried tones. She counted. There were six Indians and four Frenchmen. Were the Frenchmen wicked, too, like the Indians?

What was going to happen next? What would their captors do with them all—this little band of women and children, and a man with arms tightly bound? Would they soon all be stretched out on the ground like Neighbor Wheelock? Or were the Indians making ready to be off with them?

Molly looked at her mother, but her face was so changed by grief and fear, she scarcely knew her. She looked at her father, who had so recently boasted there was nothing to be afraid of and she saw that he was afraid. With fear in her eyes and in her heart, she cried out weakly, “Ma…Pa…”

But they neither looked at her nor answered a word.

The Long Journey

“O

H WHERE ARE THEY

taking us?”

The words, an anxious cry, rose to Molly’s lips, but no one there gave answer.

Words poured from the Frenchmen’s lips in swift torrents, while they waved their hands and arms. The lace ruffles at their sleeves made changing patterns in the air, as they pointed up and down the valley. Indian voices now, deep-throated and guttural, were mixed with the Frenchmen’s high-pitched, nasal tones. Over their shoulders, Frenchmen and Indians stared backward. Were they alarmed and anxious?

A decision arrived at, the command,

“Joggo!”

—“March on!” was given. The confusion of words faded away and heavy silence came down. Only the shuffle of moving, feet—feet shod with hand-cobbled, cow-hide shoes, pressing the bare earth of the farmyard, and now and then the gulp of a stifled sob. Huddled together, tramping on each other’s heels, like a flock of uncertain sheep, the frightened people walked.

Molly turned back her head and looked. For reasons known only to themselves, the Indians had not burned the house. There it stood just as always, homelike and inviting in the morning sun, with smoke still coming from the stick-and-mud chimney at one side. There stood the well-sweep, the grindstone, the corncrib. There stood the barn—behind those walls of log Old Barney, the cows and calves, the sheep—all left alive, alone, with none to feed or tend them.

Past the well-sweep the little crowd walked, past the log buildings, the bee-tree, the zigzag rail fence—the rail fence that bordered the corn field. Molly loved the corn, best when the stalks were high above her head. She loved its gentle rustling, the soft words it spoke, as she walked between the rows, pulling the ears off one by one. She loved to feel the soft, warm earth ooze up between her naked toes. At the sharp memory of it all, she was seized with sudden pain.

“Oh, Pa!” she cried, but her mouth, so twisted and crooked now, was scarce able to form the words. “Oh, Pa! You said come what may, today you would plant your corn! The seed-corn was shelled and ready—the whole big dye-tub full. You said we’d stay and you’d plant your corn today. We must have corn to eat. We can’t go away…like…this…”