Indian Captive (30 page)

As the snake began to twist and turn, Molly felt suddenly faint and sick inside. “To be sick is weakness,” Turkey Feather had said. Then she knew that she had no time to be sick, no time to faint.

She snatched up the Indian baby and clutched him fiercely to her breast. She saw the snake wriggle off into the brush and escape—the blow of the stone had merely stunned it. With a tremendous relief she was glad she had not killed it. She turned and ran down the hillside. She saw Storm Cloud running, too, still frowning, dragging her basket behind her, spilling half the berries. At the bottom of the hill the women and the rest of the children came running and crowded close around her. When she caught her breath, she heard what Storm Cloud was saying:

“Blue Jay wanted to pick up the pretty snake, but Corn Tassel threw a stone and made it go away.”

Then they all began talking at once, and above the loud babble, she heard Beaver Girl’s words. “You are not hurt?” cried Beaver Girl. “Oh, I should have stayed with you. You are not hurt?”

“It was a rattlesnake,” said Squirrel Woman, briefly. “When you hear a warning rattle, you must run the other way. You must call at once for help. Blue Jay is old enough to learn…”

“But he’s only a baby…” cried Molly, indignant. “How could he know?”

“A boy of two is old enough to know that the snake’s rattle means danger!” replied Squirrel Woman, crossly.

“We’ve picked the most berries,” announced Star Flower, but nobody heard her. The number of berries picked seemed somehow no longer a matter of importance.

“Come, we will go home,” said Shining Star.

“But Panther Woman will scold!” protested Star Flower. “She wants the baskets full, so she can dry them all for winter!”

Molly did not speak. But she saw Shining Star, with sparkling eyes, pick up her boy and all the way back in the canoe hold him close. Though Shining Star spoke no word, Molly knew she had her thanks.

Molly took the paddle of Shining Star’s canoe herself. It was the first time the women had allowed her to take it, the first time she had ever paddled a loaded canoe. Smiling to herself she reached out with the paddle, and the canoe seemed to be taking her into unknown waters, but oh how glad she was to go! New strength and sureness were hers to make her path easier no matter where it led.

When they returned to the village, even Star Flower forgot to boast of the berries picked. Little Storm Cloud told her story over and over: “Blue Jay wanted to pick up the pretty snake, but Corn Tassel threw a stone and made it go away.”

“But I thought it made you sick to see an animal killed or injured,” said Turkey Feather astonished.

“I forgot about that,” said Molly smiling a little. “I thought of only one thing—that Blue Jay was in danger and I must not let the snake strike.”

“You were in danger, too!” said Turkey Feather, softly.

“I?” repeated Molly. “Oh, no, I was behind Blue Jay.”

“I wish now I’d gone to pick berries,” said Turkey Feather. “I’d like to have seen you do that. You showed more courage than an Indian girl—an Indian girl would have run away.”

“I’m glad the snake didn’t strike

you!”

cried Beaver Girl.

“When someone we love is in danger,” said Old Shagbark, “the Great Spirit makes us strong and gives us courage.”

Molly could almost hear her mother speaking and the words were much like Shagbark’s: “It don’t matter what happens, if you’re only strong and have great courage.”

“You went straight into danger…” now it was Shining Star speaking, “you thought not once of yourself…and you saved my son’s life. No member of Blue Jay’s family can ever forget. As long as you live, you will have our gratitude and his!”

Molly looked from one face to the other in surprise. Was there once a time when she had distrusted these, her dear friends? If there had ever been such a time, from this day on, it was wiped out and forever gone. The tears came now, long after the danger was over.

“Why, this don’t sound like a white gal at all! Don’t tell me a white gal’s won praise from the Senecas for bravery and courage. ’Taint possible, is it?”

It was a white man speaking in English. Molly forgot her tears and looked up in surprise. All the Indians, men, women and children, were gathered close about her, but through the crowd, a white man came pushing. Over Turkey Feather’s and Beaver Girl’s heads she saw a raccoon skin cap, with its striped tail waving in the air. Above a fringed deerskin hunting-shirt, she saw a man’s weather-beaten face all wreathed in smiles. But even before he caught her in his arms and she looked up into his

eyes,

she knew that it was Old Fallenash, the white trader.

“But I thought you were dead!” she cried. “I thought you’d never be able to come again.”

“They ain’t scalped me yet,” said Fallenash, with a twinkle in his eye, “and even after they put me under the ground, like as not I’ll be popping up again. Yes, I made out to come. I had to come to see you, Molly. I came a long way round just to see you. Laws-a-massy, seems like I been most halfway round the world!”

“Have you brought news?” asked Molly, breathless.

“No news I might have brought could please me like the news the Indians have just been tellin’,” cried Fallenash, heartily. “When they praise you for courage, Molly, it means you’ve got the real thing.”

“But I didn’t do anything…”

“Oh, come now, I heard it all,” laughed Fallenash, “so you needn’t try to be modest. They’ve took ye to their hearts now. They’ve bound ye to themselves tighter today than any adoption ceremony could do it. They’ve made ye one of themselves. You can do no better from now on than to make your home with them.”

“You’ve not come then to take me back?” asked Molly. Her heart stood still while she waited for his answer.

“No, child, and I’ll tell you why,” said Fallenash quickly. “‘Cause you ain’t got no home to go to—your home’s right here.”

“No home?” cried Molly, lifting her hand to her trembling lips.

The Indians wandered off to their lodges and left the two alone. The trader took Molly by the hand and together, in silence, they walked to the river bank. There Molly listened to his words:

“Yes, Molly Jemison, child, it’s sad news for ye I’ve brought. I’m glad to hear from the Indians that you’re a gal of courage, for you’ll need all the strength and courage you can fetch. I wouldn’t tell ye a word, if I thought you couldn’t bear it, but I know you’re strong both in body and in heart. You’ve lived with the Senecas goin’ on two years now and it’s made you strong and well-hardened. I could see it in your eyes, even if they hadn’t told me.”

“Has anything happened?” cried Molly. Her throat was dry and the words came low. “Have you had bad news? Have you been there—to Marsh Creek Hollow?”

“Yes, I have news and it ain’t good, Molly, but hold up your chin and I’ll tell ye.” He fumbled nervously with his powder horn, then held it up.

“Take a look here, will ye? I’ve-scratched out a map upon it. Here’s Marsh Creek Holler and there’s Conewago Creek and Sharp’s Run. Here’s the mountain ranges they took ye over and there’s where Fort Duquesne used to be but ain’t no more. Now, foller the River Susquehanna up north here, then skip over west and there’s Genesee Town by the great Falling Waters, where ye be standin’ this minute.”

“Yes,” said Molly, “and…”

“I’ve been back there,” said Fallenash, bluntly, “back to Marsh Creek Holler, since I saw ye last.” His words came fast now, as if their fleetness could balance the pain they would bring. “I met Neighbor Dixon and he took me over. Your Pa’s house and barn was burned the minute you got out of sight, with everything in ’em…”

“The beds and Ma’s two spinning-wheels and the loom and…?”

“Everything!” Fallenash continued. “Dixon told me how your two older brothers came and roused him, sayin’ the whole two families was took, your Pa’s and Mrs. Wheelock’s. He got the neighbors together and they started hot on your trail…”

“I knew they were following,” said Molly, trembling.

“They follered too close,” said Fallenash, sadly. “It would have been better for your folks if the neighbors had stayed to home. They follered too close for the Indians’ comfort. That’s why the Indians took you and the Wheelock boy and left the others behind…and killed them…”

“Killed them?” gasped Molly. “All this time… they’ve never been alive at all?”

“They’ve never been alive since the day after you left them,” said Fallenash, in a low voice. “You see, the Indians couldn’t get away fast enough with so many prisoners. They were afraid the pale-faces might catch up. You’re lucky to be alive, gal, and still in your skin.”

Molly hid her face in her two hands. She cried out, in a muffled tone: “Then I’ll never see them again…Pa and Ma and Betsey and the boys and the little ones?”

“Your two older brothers might be alive somewhere,” said Fallenash, with sorrow in his voice. “Nobody knows. They ran off to the southward, so Dixon thought. But, for the others, their troubles are well over. They didn’t suffer the half of what you did, gal!”

“You can’t take me then…” said Molly, slowly. She looked up and in her eyes there were no tears. “Because I’ve no home or family to go to…”

“You’re right, I can’t!” said Fallenash. Then in a relieved tone, he added laughing: “Oh, Molly, I most forgot to tell you. My Indian woman’s got a baby—an Indian baby as brown as any in this village. Won’t it be funny for him to call Old Fallenash Pa?”

“Ah Indian baby of your own?” asked Molly, with a crooked smile.

“Yes,” said Fallenash. Then he began to boast: “I’ll teach him to shoot with bow and arrows. I’ll teach him to dance and beat a drum. I’ll make a great warrior out o’ him. By the way, I won’t be seein’ you again…”

“Oh, Fallenash, where are you going?” cried Molly.

“Them English—they keep me on the run,” said Fallenash, his sharp eyes flashing. “Wherever I go, the French and the English foller me and start their fightin’. I only come back this way to bring ye the news, ’cause I figgered ye ought to know and not go on hopin’ and makin’ yourself miserable to the end of your days.”

“Yes, it is better to know,” said Molly, “and not go on hoping.”

“Now I’ve got to move on,” said Fallenash. “I always had a hankerin’ to try the climate of Quebec so we’re takin’ a little canoe ride, me and my family. When them English take Quebec, only the Lord knows what’ll become of Old Fallenash.”

“Then where will you go?” asked Molly.

“I’ll find a little corner somewhere, where there ain’t no French or English to bother—me and my Indian woman and my little warrior! We can look out for ourselves. Don’t worry none ’bout us.”

“Thank you for coming such a long way just to tell me,” said Molly. “I’d have liked to see your Indian baby…”

“Try to be happy!” said Fallenash, kindly. “You ain’t so bad off, after all.”

“This is the only home I have now,” said Molly. She watched the trader start off. “I hope you’ll find some place to go to, after they take Quebec…”

She waved her hand till he was out of sight. “How good he is!” she said to herself. Then, like a young thin sapling, broken by cruel winds, she sank to the ground.

Born of a Long Ripening

S

EVERAL DAYS LATER, AT

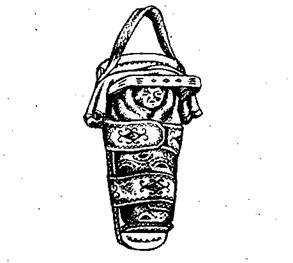

noon, Molly walked slowly to the spring, carrying her water vessel. She wore the new cloth garments which Shining Star had made for her. She studied the embroidered tree pattern on her skirt as she walked along. At the spring, she was surprised to see Gray Wolf waiting.

“The English Captain has come,” he announced.

“Who? What?” asked Molly.

“Captain Morgan has come with a message from Sir William Johnson to Chief Burning Sky. Sir William Johnson is glad to know that he can count on the help of the People of the Long House. He sends word that Quebec has been taken by the English and all the French soldiers have been withdrawn. Soon he will be raiding the frontier settlements and sending out war parties.”

“What is that to me?” said Molly, with scorn in her voice. “With war I have nothing to do. That is the affair of the Chief and the sachems. Go, speak to them.” She shivered, then bent over to fill her vessel, so that she might hurry back.