Icon of Evil: Hitler's Mufti and the Rise of Radical Islam (13 page)

Read Icon of Evil: Hitler's Mufti and the Rise of Radical Islam Online

Authors: David G. Dalin,John F. Rothmann

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Middle East, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #World War II, #History, #Israel & Palestine, #World, #20th Century

As he sat with his young cousin, the mufti saw a future filled with promise. Here was a young man, he mused with satisfaction, who was learning well the lessons that the mufti sought to teach the next generation. Realizing that his credibility had been compromised by years of political intrigue, and facing the grim reality of his advancing age, he recognized that in his young cousin he could see his dreams fulfilled. In giving his blessing to Arafat, the mufti realized, he was ensuring the future of his vision.

Al-Husseini would also share with Arafat his plans for resuming his position as president of the Arab Higher Committee for Palestine, and thus as the unchallenged leader of the Palestinian Arabs, as well as his dreams of becoming the recognized leader of radical Islam throughout the Middle East. Founded in 1936, the Arab Higher Committee had been disbanded by the British mandatory government, which had held the mufti and his associates in the committee responsible for the 1936 Arab riots that had taken hundreds of British and Jewish lives in Palestine.

9

The mufti’s plans to resume his leadership were facilitated by his cousin and close associate Jamel al-Husseini, who shortly after the war had been permitted by the British mandatory government to return to Palestine.

10

Within weeks of Haj Amin al-Husseini’s arrival in Cairo, his cousin Jamel had announced the reactivation of the Arab Higher Committee as the official representative of the Arabs of Palestine and, together with Hassan al-Banna, publicly urged the reinstatement of Haj Amin as its president. There was no question as to who was to be the leader of the committee. Testifying before the Anglo-American Committee on Palestine (a blue-ribbon commission established jointly by the British and American governments to make policy recommendations concerning the future governance and political leadership of Palestine), Jamel al-Husseini stated emphatically that the Arabs of Palestine “find themselves deprived of their chief leader, the Grand Mufti, for whom they cannot accept any substitute.”

11

The mufti alone, reiterated Jamel al-Husseini, could speak on behalf of the Arabs of Palestine. The issue of Haj Amin al-Husseini’s involvement with Nazi Germany did come up during the committee hearings; but despite the overwhelming evidence against him, realpolitik prevailed, and his reinstatement as president of the Arab Higher Committee was approved by the Anglo-American Committee.

The Mufti’s All-Palestinian Government for Palestine

In the aftermath of the creation of the state of Israel in May 1948, much of the mufti’s time and energies were devoted to his goal of establishing a new All-Palestine Arab government in Palestine. On May 15, 1948, the day after Israel declared its independence, the Arab Higher Committee announced its intention to set up such a provisional government, under the presidency of al-Husseini, with its capital in Jerusalem (or, if that was not possible, in Nablus).

12

After twelve years in exile, al-Husseini longed to return to the city of which he was nominally the mufti and to assume the presidency of a Palestinian state.

In Cairo, on January 5, 1948, his Arab Higher Committee had first publicly announced its intention of establishing a new Palestinian Arab government as soon as the British mandatory government departed Palestine and the anticipated declaration of Jewish statehood took place. Recognizing that events were moving quickly—the end of the British Mandate was scheduled to take effect on May 15—al-Husseini acted decisively. On March 30, 1948, he had presented to the United Nations a formal Arab charter for Palestine. Although not binding in any way, it declared the claim of the Arabs, represented by al-Husseini’s Arab Higher Committee, to sovereignty over all of Palestine.

On September 27, 1948, the Arab Higher Committee for Palestine convened in Gaza and announced the formation of the All-Palestine government. On September 28, al-Husseini arrived in Gaza. It was a momentous moment, as it was the first time since his departure in 1937 that he stood on Palestinian soil. It was a joyous day. The decision to create Hukumat ’umum Falastina, the All-Palestine government, was the first step in what he believed would lead to the liberation of all of Palestine. On September 30, amid much fanfare, al-Husseini was unanimously elected by the delegates as president. Assembled around him were many of his comrades in arms from the 1936 intifada.

A formal photo session followed, at which the mufti and his supporters joyously proclaimed the establishment of a free, democratic Arab state in the whole of Palestine. With that announcement came the formal Declaration of Independence by the new government: “Inasmuch as the Arab Palestine People have the sacred natural rights for freedom and independence so far subdued by British colonialism and Zionism, we, members of the National Assembly, meeting in Gaza, declare on October 1, 1948, the independence of all Palestine, full independence, and the establishment in all Palestine of a free democratic state in which freedom and equal rights are guaranteed to all citizens; and in line with its Arab sister states to carry on in the building of Arab culture and glory.”

13

As president of the new government, al-Husseini chose as his prime minister his close friend and associate Ahmed Hilmi Abd al-Baqi.

On October 12, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon recognized the All-Palestine government. Jordan, however, did not agree to recognition. King Abdullah, who had a pathological distrust (indeed, hatred) of al-Husseini, immediately made it clear to other nations in the Arab League that he would strongly oppose the creation of an independent Palestinian government headed by the mufti,

14

which would have thwarted Jordanian hegemony in Palestine. Moving quickly, Abdullah convened the Palestine Arab Congress in Amman, denounced the mufti’s new Palestinian government, and called for Jordan to play an active role in the future of the area.

Meanwhile, the United States made its position clear. On October 14, Acting Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett announced that the United States would not grant recognition. Lovett stated four reasons for the U.S. decision. First, the United States had granted de facto recognition to Israel on May 14 and would not recognize a government that claimed land already under the authority of an established, recognized government. Second, in the judgment of the United States, the All-Palestine government had not conformed to the normal attributes of government, as it could not perform even the most minimal administrative or governmental functions. Third, it had not held elections; and fourth, it did not control the area over which it claimed sovereignty. The United States pointed out that Egypt controlled Gaza, Jordan controlled what was soon to be known as the West Bank of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, and Israel had sovereignty over the balance of what had been British mandatory Palestine.

On December 1, the Second Palestine Arab Congress convened in Jericho, then controlled by Jordan. To no one’s surprise, the congress invited King Abdullah to unite the existing Kingdom of Jordan with the area of Palestine under Jordanian control. On December 13, the Parliament of Jordan approved the request. Despite vigorous protest by al-Husseini and his All-Palestine government, de facto annexation took place on May 17, 1949, when the Jordanian military government over the area was replaced by a civilian administration. On April 11, 1950, elections for a new Jordanian Parliament were held on what was then called the East Bank as well as in the newly annexed West Bank of the Kingdom of Jordan. On April 24, the newly elected Parliament ratified the annexation.

The fury of Haj Amin al-Husseini knew no bounds. He had been betrayed. His government was a fiction. It controlled no land. To add insult to injury, the Egyptian government of King Farouk, which had so warmly welcomed the mufti to Cairo only two years earlier, ordered the All-Palestine government out of Gaza. The Egyptian government had come to view the All-Palestine government as a political and diplomatic liability and as an embarrassment. Against his will, al-Husseini was relocated to Egypt, where he lived with his freedom of movement severely restricted.

15

Photo Insert

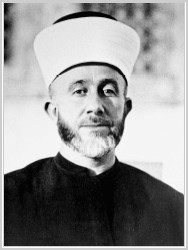

Portrait of Haj Amin al-Husseini, at the height of his power, in Jerusalem, 1937: grand mufti of Jerusalem, president of the Supreme Muslim Council, president of the Arab Higher Committee for Palestine.

©

CORBIS-BETTMANN

Al-Husseini awaits his first meeting with Adolf Hitler in the Reich Chancellery, Berlin, November 28, 1941.

©

BAYERISCHE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK MUENCHEN

Hitler and al-Husseini, November 28, 1941.

©

ULLSTEIN BILD / THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NEW YORK

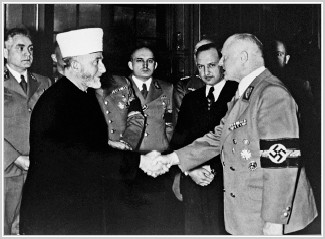

Al-Husseini shakes hands with an unidentified Nazi official during a reception in Berlin, circa 1941–1943.

©

USHMM, COURTESY OF CENTRAL ZIONIST ARCHIVES