Hunter Killer (14 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

The al-Qaeda commander paused. And before him he saw many heads shake, mostly in astonishment. There were also many nods of approval at his words. The numbers he quoted were indeed quite shocking. But there was a more shocking one to come.

“Twenty years ago,” said Captain Rahman, “my country held cash reserves of a hundred twenty billion dollars. Today those reserves are down to less than twenty billion. Because of our close involvement with the United States, the government is paying ‘protection money’ to al-Qaeda. Hundreds of millions of dollars. Saudi Arabia was paying the Taliban to ‘protect’ Osama bin Laden.

“The battle we are about to fight in the hills of southwestern Saudi Arabia, and in the streets of Riyadh, is not revolution, nor even

jihad

. We are fighting to purify a country that has gone drastically wrong.”

A young French soldier, deadly serious, called out, “And there really is a feeling in the country that will help us to achieve our victory?”

“Stronger than you will ever know,” replied the Captain. “In the mosque schools all over the country they are turning out young men who have been taught to follow the old ways, the customs of the Bedouins, the ones who represent our roots. We are a natural people of the desert, but our enemies in neighboring countries are closing in around us. Almost the whole of Islam believes we have let down the Palestinians, failed to help them in the most terrible injustices committed against them by the Zionists.

“Other Arab leaders feel we have allowed Islam to be humiliated. And, in a sense, that is precisely what the government of Saudi Arabia has allowed to happen. We were all born to be a God-fearing nation, following the words of the Koran, the teachings of the Prophet, helping the poorer parts of our nation, not spending ninety million dollars on a vacation like King Midas.”

At this point, General Rashood himself looked up. “Every Arab knows that the situation in Saudi Arabia cannot continue. There is too much education for that. I believe I read somewhere that two out of every three Ph.D.’s awarded in Saudi Arabia are for Islamic studies. The Saudi Arabian royal family’s greatest threat is from within. The clerics are teaching truth. It’s just a matter of time before the whole thing explodes.”

“Just a matter of time,” said Captain Rahman. “And I believe we will hasten that time. And the good Prince Nasir will come to power and make the changes we must have. I know this seems a very ruthless, reckless way of attaining our ends, but it is the only way. And the new Saudi ruler will owe a debt of gratitude to France that may never be repaid.” The Captain hesitated before adding, with a smile, “But I understand he will most certainly try.”

General Jobert stood up and announced, “I will now call out the members of each team. Your commanding officers have given this considerable thought. But the three teams of eighteen men have very different tasks, and the command headquarters situated in the hills close to the action also has a critical role to play.

“Please now, everyone pay attention while I make a roll call:

Team One, air base assault…commanding officer Major Paul Spanier…

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY

7, 0830

PORT MILITAIRE

BREST

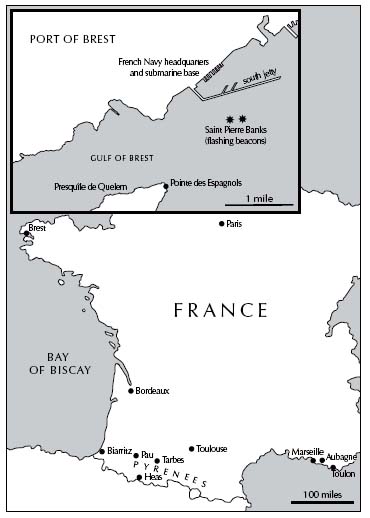

Two hundred and fifty miles to the west of Paris is the sprawling headquarters of the French Navy, around the estuary of Brest, where the Penfeld River runs into the bay. This is the western outpost of Brittany, home to France’s main Atlantic base, where they keep the mighty 12,000-ton Triomphant-class ballistic-missile submarines. Not to mention the main Atlantic strike force and, from 2005, the French attack submarines, the hunter-killers.

Adm. Marc Romanet, Flag Officer Submarines, and Adm. Georges Pires, Commander of the French Navy’s Special Ops Division, were standing in a light drizzle wearing heavy Navy top-coats, right out at the end of the south jetty, beyond which France’s submarines swung to port for entry into their home base.

They could see her now, way down in the bottleneck, over two miles to the west, on the surface, making six knots up the channel in twenty fathoms. Through the glasses Admiral Romanet could see three figures standing on the bridge. One of them he knew was the young commanding officer, Capt. Alain Roudy.

His submarine was called

Perle

, hull S606, right now the most important ship in the entire French fleet. This was the SSN that would attack the oil fields of Saudi Arabia, the lethal slug of war that would release four boatloads of frogmen to blast the great Gulf loading bays to smithereens. And then fire its missiles from the depths of the Persian Gulf, knocking out the huge oil complex of Abqaiq and slamming Pump Station Number One, halting the flow of the kingdom’s lifeblood,

This was she. The 2,500-ton

Perle

, fresh from her refit in Toulon, now with a much smaller but no less powerful nuclear reactor, and her new, almost silent primary circulation system, which probably made the

Perle

’s propulsion unit the quietest in all of the undersea world.

She’d been down in France’s Mediterranean Command Base for her major refit for almost six months. And she was a lot more important today than she was last May when she went in. At that time it had been assumed that the Saudi mission would be carried out by one of the brand-new boats scheduled to come out of Project Barracuda. But that program had been subject to mild but critical delay, and Prince Nasir could not wait.

He had been to see the President three times. And three times the President had insisted that the Navy move fast, in two oceans, and cripple the Saudi oil industry before the new year of 2010 was more than three months old.

The three men who had principally to deal with that request were the two Admirals who now stood at the end of the south jetty, plus their guest, who was currently sheltering from the rain in the Navy staff car parked beneath the bright quick-flashing harbor warning light at the tip of the jetty, Gaston Savary, France’s Secret Service Chief.

Admiral Pires had invited Savary to visit because he knew the pressure under which the President had placed him. He considered the least he could do was to show Savary the underwater warship upon which all of their hopes, and probably their careers, depended.

Tonight there would be a small working dinner at Admiral Romanet’s home, where Savary would meet the commanding officer, and much would be explained. This was to be the first briefing for Captain Roudy. And, privately, Savary thought he would probably have a heart attack. It was not, after all, an everyday mission.

“Gaston, come out here!”

called George Pires.

“I’ll show you our ship!”

Savary stepped out into the rain and accepted the binoculars handed to him. He stared out down the channel and saw the

Perle

sweeping through the water, a light bow wave breaking over her foredeck, the three figures in uniform, up on the bridge, looking ahead.

The three men stood in the rain for another fifteen minutes, watching the submarine drift wide out to her starboard side, staying in 100-feet water, as she skirted around the Saint-Pierre Bank, a rise in the ocean floor that shelved up to only twenty-five feet in two places.

Almost directly south of the harbor entrance she made her turn, hard to port into the channel, and headed in. Her jet black hull seemed much bigger now, and more sinister. She was, in fact, the most modern of the Rubis Améthyste class, commissioned back in 1993. But Naval warships do not get old, they have everything replaced. And now the

Perle

not only packed the normal hefty punch of her Aerospatiale Exocet missiles, which could be launched from her torpedo tubes, she also carried a new weapon—medium-range cruise missiles. These could be launched from underwater, using satellite guidance, and could literally thunder into a target several hundred miles away, traveling at Mach 0.9, just short of the speed of sound.

She looked a symbol of menace. And according to the rare communications she made with her base, while crossing the Bay of Biscay for home, she had performed perfectly. And above all, quietly.

The Toulon-based engineers at the Escadrille des Sous-Marins Nucléaires d’Attaque (ESNA) had done their precision work superbly.

“That looks like a dangerous piece of equipment,” said Gaston Savary, as the sub came sliding past the jetty without a sound.

“That is a very dangerous piece of equipment,” replied Admiral Pires as he turned seaward to return the formal salute of Capt. Alain Roudy, high on the bridge.

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY

7, 2100

OFFICIAL RESIDENCE

FLAG OFFICER SUBMARINES

ATLANTIC HQ, BREST

There were five men, each of them sworn to secrecy, each of them in uniform, standing around the wrong end of Adm. Marc Romanet’s long dining room table. The other end contained five place settings and two bottles of white Burgundy from the Meursault region.

But this was officially pre-dinner. And down there at the business end was spread a whole series of naval charts and photographs being studied carefully by the two Admirals, Romanet and Pires, plus Capt. Alain Roudy and Cdr. Louis Dreyfus, commanding officer of the

Améthyste

, the

Perle

’s sister ship.

These were the two submarines selected by the French Navy to cripple the economy of Saudi Arabia, and half the free world. Or, stated another way, to free up the wealth beneath the Saudi Arabian desert for the overall benefit of the Saudi nation. Or, alternatively, to return the Saudi government to the ways of Allah and to the purity of the Prophet’s words. It all depended upon your point of view.

The fifth member of the group, Gaston Savary, was standing behind the Naval officers, sipping a glass of Burgundy and listening extremely carefully. He would be in front of the French Foreign Minister, Pierre St. Martin, in Paris the following afternoon, for a debriefing. The decision of the four men with whom he was dining tonight would determine, finally, whether this mission was Go or Abort.

The issue being discussed was the Red Sea, the 1,500-mile stretch of ocean that was Saudi Arabia’s western border. The Suez Canal formed the northern entrance, and the French submarines would, by necessity, make this transit on the surface.

They would travel separately, probably two weeks apart. Only the

Améthyste

would remain in this deep but almost landlocked ocean to carry out its tasks. The

Perle

would continue on and exit the Red Sea at the southern end, before proceeding up the Arabian Gulf and into the Strait of Hormuz, en route to its ops area, north of Bahrain.

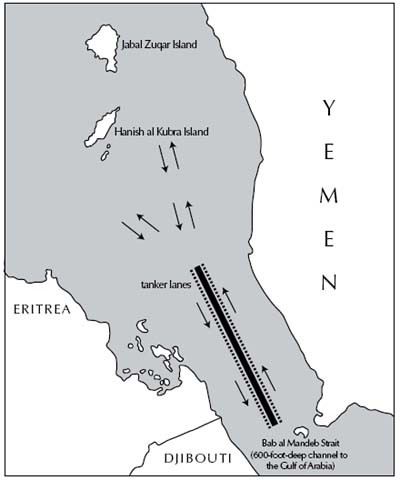

The point was, could Captain Roudy make the southern exit underwater out of the range of prying satellites and American radar? Or would he need to come to periscope depth in order to move swiftly through the myriad islands that littered the ancient desert seaway before making his run out through the narrows and into the Gulf of Aden?

With the sandy wastes of Yemen to port, the

Perle

would pass to starboard the long coastline of Sudan, then the equally long shores of Eritrea, then Djibouti, before making the deepwater freedom of the Gulf of Aden. But the final 300 miles, past the Farasan Bank and Islands, follows a route where the water shelves up steeply on the Yemeni side, from 3,000 feet sometimes to 20 feet, which is precisely its depth off Kamaran Island.

The exit from the Red Sea is a long trench, narrowing all the way, with the island of Jabal Zubayr stuck right in the middle. Then there’s Jabal Zuqar Island, and Abu Ali Island, both with bright flashing warning lights, which are totally useless to a submarine trying to crawl along the sandy depths of the 600-foot-deep channel. The rise of Hanish al Kubra is a navigator’s nightmare, almost dead center in the channel, which is now only 300 feet deep and only about a mile wide.

However, there are two navigational channels there. One, with routes north and south, runs to the east of Jabal Zuqar, close to Yemen. It is shaped in the dogleg of the island’s west coast. The other marked channel runs twenty-five miles to the southeast and skirts the western side of Hanish al Kubra. Essentially, it comprises two narrow seaways, north–south and fourteen miles apart, running alongside a series of rocks, sandbanks, and shoals. These are the trickiest parts because of the narrow channels, which skirt a couple of damned great sandbanks, one of them only sixty-five feet from the surface. However, this stretch, which does need the greatest navigational care, is the final black spot for the submariner.

Thereafter, both south routes converge into a forty-five-mile-long marked seaway, which suddenly shelves up again, to less than 150 feet, but has the advantage of being dead straight all the way to the southern strait, gently falling away again, to a depth of 600 feet.

In places it narrows to a few hundred yards, with a very shallow shoal to port, but it runs on into the Strait of Bab el Mandeb and then into the Gulf, into depths of 1,000 feet plus, right off Djibouti—and the U.S. base west of the Tadjoura Trough.

“Think you can handle that, Captain Roudy?” asked Admiral Romanet.

“Yessir. If those chart depths are accurate, we’ll get through without being seen. Under seven knots in the shallow areas, but we’ll be all right.”

“The charts are accurate,” said Admiral Romanet. “We sent a merchant ship through there a month ago using sounders all the way. We checked depth against chart depth from Suez to Bab el Mandeb. The charts are correct.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Captain Roudy. “Then the GPS will see us through the southern end. I’ll run with the mast up.”

“Very well,” replied Marc Romanet, who was well aware of the tiny GPS system, positioned at the top of the periscope of the refitted Rubis

.

It was not much bigger than a regular handheld unit, and it would stick out of the water a matter of mere inches. The

Perle

’s CO had plenty of depth for that. And that minuscule system, splashing through the warm, usually calm waters of the Red Sea, would always put Alain Roudy within thirty feet of where he wanted to be.

“Before we dine I would like to go over the plan for the

Améthyste,

which will be following you through the Suez Canal almost three weeks later,” said the Admiral. “Commander Dreyfus, you will, of course, run straight down the Gulf of Suez along the Sinai Peninsula and into the Red Sea at the Strait of Gubal. Have you done it before?”

THE DEEP-WATER CHANNEL—SOUTHERN EXIT FROM THE RED SEA

“Nossir. But my executive officer has. And so has my navigation officer. We’ll be fine.”

Admiral Romanet nodded and looked back to his chart. “Your ops area is about halfway down the Red Sea, in waters mostly around five hundred meters deep. We have decided this is not a perfect area for an SDV (swimmer delivery vehicle), and anyway our Rubis submarines are not ideally equipped to carry one. Instead our SF will make the transit from the submarine in two Zodiac inflatables, six men to a boat. The outboard engines run very quietly, and the guys can row in the last few hundred yards for maximum silence.

“We have targets at Yanbu and Rabigh, enormous terminals, with these huge loading docks, in the picture here…” The Admiral pointed with the tip of his gold ballpoint pen. “They will be separate operations, ninety miles apart. The plan is to attach magnetic bombs to the supporting pylons, utilizing timed detonators, and then have the lot crash into the sea at the same time.

“At nineteen hundred, as soon as it’s dark, the Special Forces will leave the submerged submarine, which will be stopped around five miles offshore. That gives them a fifteen-minute run-in, making thirty knots through the water in the Zodiacs. Two boats. The submarine will wait, pick them up, then travel quietly down to the loading bays at Rabigh, arriving at around o-two-hundred.

“There is no passive sonar listening in that part of the Red Sea, nothing before Jiddah, a hundred ten miles farther on, where the Saudi Navy has its western Navy HQ. That’s a big dockyard, with vast family accommodation: mosques, schools, et cetera. But its only real muscle is three or four missile frigates, all French-built, bought directly from us. We’re experts on what they can and cannot do. And anyway we’re not going that far south.

“The chances of the Saudis’ picking up a very quiet nuclear submarine running several miles offshore is zero. And even if they do, there’s not much they can do about it. They have virtually no ASW capability. And even if they did send out a patrol boat, even a frigate, for whatever reason, we’d either hide easily or sink it.”

Commander Dreyfus nodded. “Same procedures as Yanbu for the Special Forces? Send in two Zodiacs and wait?”

“Correct. Then you will move out to sea…you’ll be around halfway between Yanbu and Jiddah…make your ops station somewhere here…” The Admiral pointed again to the chart. “Correlate your timing,” he said, “with the bombs on the loading dock pylons. I want them all to go off

bang

at precisely the same time.

“So you will open fire simultaneously with the cruises, seven and a half minutes before H hour on the pylons. You will fire three preprogrammed batteries, four missiles in each. The first four straight at the Jiddah refinery, then four at the main refinery in Rabigh. And one into the refinery at Yanbu, right on the coast…here…directly north of your hold-area position.”

“Fire and forget, sir?”

“Absolument.

The moment the birds are away, steam southwest, out into the deepest water, then proceed south toward the Gulf of Aden. Stay submerged all the way. Then move into the Indian Ocean. Proceed south in open water, still submerged, to our base at La Reunion, three hundred miles off the west coast of Madagascar, and remain there until further notice.”

“Sir.”

“I think, gentlemen, we should dine now. And perhaps outline our plans for the Persian Gulf with Captain Roudy as we go along?

D’accord?”

“D’ac,”

said Georges Pires, jauntily using the French slang for “in agreement.” “This kind of talk is apt to dry the mouth. I think a few swallows of that excellent Meursault up there would alleviate that perfectly.”

“Spoken like a true French officer and gentleman,” said Gaston Savary.

Admiral Romanet seated himself at the head of the table, with Georges Pires to his left and Savary to his right. The two submarine commanding officers held the other two flanks. Almost immediately a white-coated orderly arrived and served the classic French coquilles Saint-Jacques, scallops cooked with sliced mushrooms in white wine and lemon and served on a scallop half-shell with piped potato.

The orderly filled their glasses generously. For all four of the visitors it was much like dining at a top Paris restaurant. The main course, however, provided a sharp reminder that this was a French Naval warship base, where real men did not usually eat coquilles Saint-Jacques.

Admiral Romanet’s man served pork sausages from Alsace, the former German region of France. There was none of the traditional Alsace sauerkraut, but the sausages came with onions and

pommes frites

. It was the kind of dinner that could set a man up, just prior to his blowing out the guts of one of the largest oil docks in the world.

The golden brown sausages were perfectly grilled, and they were followed by an excellent cheese board, containing a superb Pont l’Evêque and a whole Camembert

…les fromages,

one of the glories of France. And only then did the waiter bring each man a glass of red wine, a 2002 Beaune Premier Cru from the Maison Champney Estate, the oldest merchant in Burgundy.

Admiral Pires considered that, one way or another, the Submarine Flag Officer at the Atlantic Fleet Headquarters in Brest was a gastronomic cut above the hard men who lived and trained at his own headquarters, in Taverny. But Admiral Romanet, a tall, swarthy ex-missile director in a nuclear boat, was still concerned with the business of the evening. He had replaced the wine glass in his right hand by a folded chart of the Persian Gulf waters to the east of Saudi Arabia. And he now considered that he knew Captain Roudy sufficiently well to address him by his first name.

“Alain,” he said, “I think we have established that your exit from the Red Sea can be conducted submerged. And, as you know, it’s a two-thousand-mile run from there up to your ops areas in the Persian Gulf.

“As you know, it’s also possible to enter the Gulf, via the Strait of Hormuz, underwater. The Americans run submarines in there all the time. However, it’s not very deep, and some of the time you’ll have a safety separation of only thirty-five meters in depth, which does not give you a lot of room, should you need to evade.

“However, I don’t think anyone will notice you because they won’t be looking. The Iranians on the north shore are so accustomed to ships of many nationalities coming through Hormuz, they are immune to visitors.

“Your real difficulties lie ahead…up here, north of Qatar. And that’s your new ops area. You’ll need to run north, straight past the Rennie Shoals…right here…marked on the chart. You’ll leave them to starboard, but I don’t think you should venture any closer inshore. You want to stay north, right around this damned great offshore oil field…what’s it called? The Aba Sa’afah. There’ll be some surveillance there, and it’s marked as a restricted area, so you’ll stay as deep as you can.

“Now, the main tanker route is right here…this long dogleg, about a mile to starboard. It’s half a mile wide coming out, and about the same running in. It’s deadly shallow, between twenty-five and thirty-five meters, which you don’t need. And all around it, the deep water is starting to run out. This is a dredged tanker channel and it’s the only way inshore if you want to stay submerged, at least at periscope depth.