How Music Works (55 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

According to St. Augustine (around 400 CE), all men would hear this sound just before they died, at which point the secret of the cosmos would be revealed—

which is very exciting, although just a little late to be of much use. This secret was passed down through the ages, from prophet to prophet, although at some

point, according to Renaissance philosophers, it was lost. Oops.

Pythagoras was convinced that each musical scale, the varieties of that

cosmic mode, have profound, specific, and unique effects on people. The

Hypophrygian mode is one of the many variations of the diachronic scale where the intervals between notes have been altered. For example, a C scale (all white keys) and a C-minor scale are two different modes. According to Pythagoras, a tune in the Hypophrygian mode could totally sober up a drunk young man.

In his day, the power of music was commonly accepted, and there were music-

based healing centers throughout Greece. The notes of the basic scale were

associated with the Muses, and each tone had its own attributes and tempera-

ment. The seven planets that the Greeks could see had associations with the

seven vowel sounds of Classical Greek, which were also considered sacred.

The various names of God were formed out of recombinations of these vowels

and harmonies—like Ho Theos, or God, Ho Kurios, or Lord, and Despotes,

which means master, and is the root of our word despot. The cosmic harmonies informed every aspect of life—our speech, our bodies, and our state of mind.

The weather, the cycles of crops, disease and health.

These musical and mathematical correspondences among all things were

out there, and the idea was that we needed only to discover them. God, or

the gods, put them there, and in the emerging Western tradition, the goal

306 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

of science and the arts was to decode what the gods had written. The belief

that the goal of science is to unearth pre-existing patterns forms the basis of much of scientific practice today. Even in the periodic table of the elements, where all the materials that make up our world are ordered according

to atomic weight, there are “harmonies.” John Newlands, who worked on the

table, discovered in 1865 that “at every eighth element a distinct repetition of properties occurs”—a pattern which he called the Law of Octaves.2 Newlands

was ridiculed, and his paper on the subject wasn’t accepted. But when his

prediction that “missing“ elements should therefore exist was later proven

to be true, he was recognized as the discoverer of the Periodic Law. “Musical”

relationships, it seems, are still viewed as governing the physical world. The Music of the Spheres idea is, in slightly altered form, still with us.

The astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler published his book

Harmo-

nices Mundi

in 1619. In it he proposed that it was the Creator who “decorated”

the whole world, using mathematical and musical harmonic proportions. The

spiritual and the physical are united. In a search for these proportions, Kepler first suggested that the varieties of polyhedral shapes—three-dimensional

figures made of pentagons, octagons, etc., and each nested inside a sphere and inside each other—might have guided the Creator’s plan.D

Kepler wasn’t satisfied with its accuracy, so he looked at the musical and

mathematical harmonic proportions. He wrote: “The Earth sings Mi, Fa, Mi:

so that even from the syllable you may guess that in this home of ours

mi

sery and

fa

mine hold sway.”3 His calculations seemed to imply that the orbits of the planets had some wobble in them, and the resulting vibrato was sometimes

unsettling and even discordant. This was not good. However, it did seem that they sometimes fell into perfect harmony—and one of these moments, he

believed, was the moment of creation.

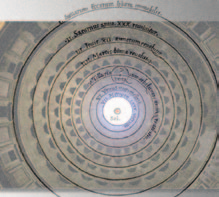

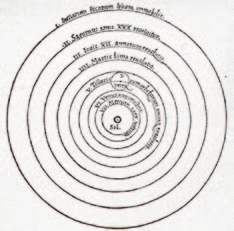

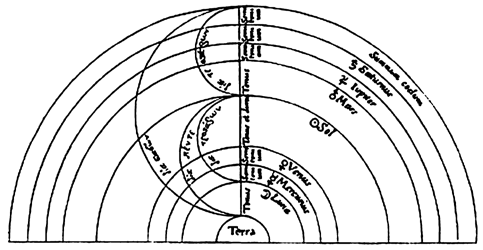

On the following page is a simple chart from

Stanley’s

History of Philosophy

, published in the

1600s, that shows the musical intervals that

D

would naturally occur on an imaginary string

stretched from the highest heaven, through Earth,

and via the orbits of the various planets (which

included the sun in the midst of the others rather

than at the center, as that was where we, on Terra,

were thought to reside).E

DAV I D BY R N E | 307

The great seventeenth-century alchemist and scientist Robert Fludd made

further elaborate renderings. He called the imaginary string the Mundane

Monochord. “Mundane” refers to the whole world in this case, not to some-

thing banal and ordinary. At the top in his drawing, God’s hand is reaching in to “tune” the universe.F

In both Fludd and Stanley’s view, seven musical modes—which are sort of

the equivalent of scales—correspond to the seven planets. Each planetary orbit and its mode had a character, such as saturnine (gloomy) or mercurial (fickle).

Each musical key, as it were, was therefore associated with personality traits we might find in our fellow humans. Astrology—the influence of the heavens on

our personalities—was in this way being given some “scientific” basis.

This idea of a universe ordered according to musical harmony fell into

disrepute and was more or less forgotten for hundreds of years, but recently it has been picked up by, of all people, the movie editor and sound designer Walter Murch. I saw Murch give a talk, and though he did discuss sound

in films and his thoughts on editing, what he was really excited about was

reviving the idea of cosmic ratios. Murch wondered why Copernicus, who

gets credit for proposing the sun-centric solar system, would make such

an unintuitive and dangerous statement. A heliocentric system was unin-

tuitive because, from our point of view, it really does seem like the stars and sun revolve around us. It was dangerous, because it was assumed that God

made the universe the way the church said He made it—Earth-centric—and

E

308 | HOW MUSIC WORKS