How Music Works (47 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

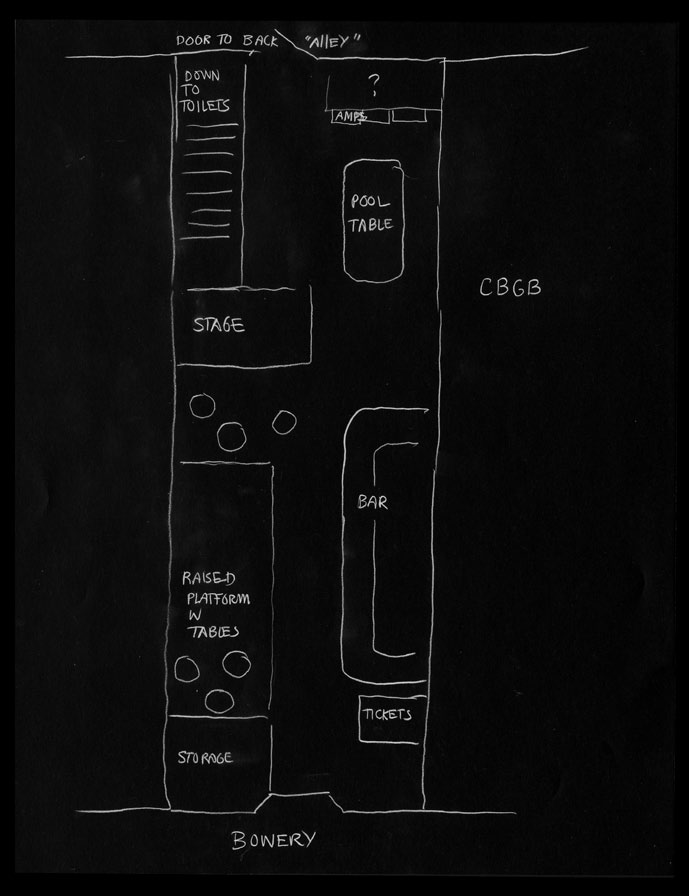

be facing away from you) or while waiting for the next band to go on. CBGB

was long and narrow, and only a small group of fans could actually stand in

front of the stage. Most of the audience would end up at the bar, or hanging around the pool table, and those people behind the bands were often barely

paying attention. It doesn’t sound ideal, but maybe

not

having to perform under intense scrutiny (it always seemed as if only the few folks in front were really paying attention) is important, even beneficial. This odd, relaxed, and even somewhat insulting arrangement allowed for more natural, haphazardly

creative development.

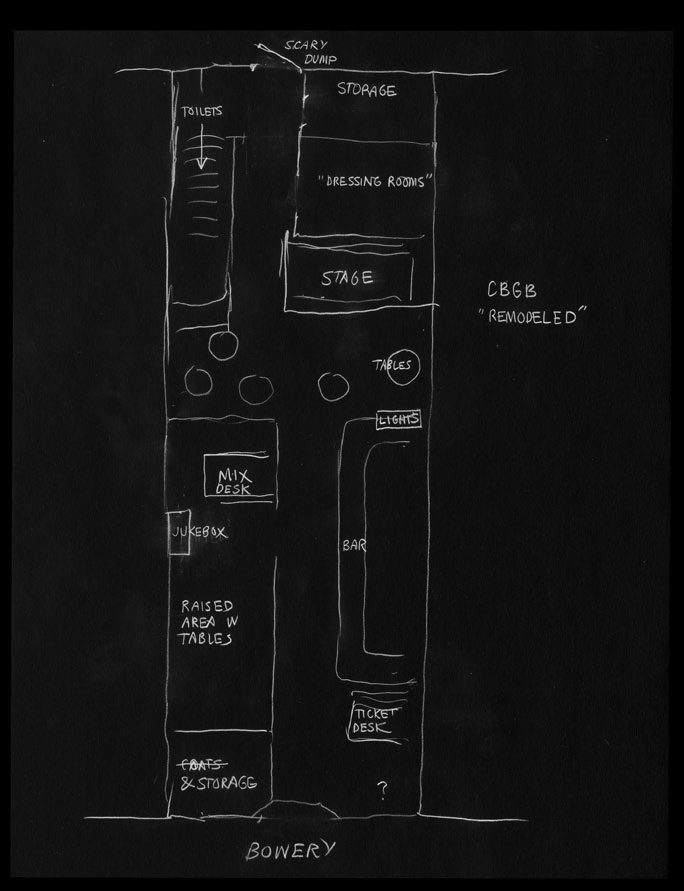

Later, Hilly resituated the stage (I am avoiding the word “remodeled”) and

improved the sound system, which made CBGB one of the best-sounding

rooms in town.D This seems incredibly enlightened—the sound system part,

anyway. Most club owners are loath to make technical improvements. As long

as drinkers are congregating at the bar, why should they? I think Hilly had

ulterior motives. I think he pictured a whole series of live recordings being made there that could have been another potential source of income for him.

But who knows? Maybe he was just being a decent guy!

In a way, the casual set-up reminded me of busking. When playing on the

street, it was never hard to get one or two curious folks to stop and listen, but if you could get the ones who were walking purposely on their way somewhere

else to pay attention, then you’d really made a breakthrough. Sometimes the

person who seemed to have been playing pool all night was the one who came

up to you afterward and said something that proved that they were the one who had really been listening.

THE LEGACY OF A SCENE

After some of the bands that emerged from CBGB were signed, they

played there less and less. They went on the road or holed up writing

and rehearsing new material, becoming a tiny bit more professional. Talking

Heads was one of those bands. I remember writing in my East Village loft

in the late seventies and then heading to CBGB’s after I’d gotten something

down. Going out was some kind of reward for me. CB’s even found its way

into a song we wrote, “Life During Wartime,” in which the club was imag-

ined from the point of view of a member of a North American version of the

262 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

Baader-Meinhof gang—urban guerillas who missed being able to go to the

clubs where they used to hang. Being out in the world more, we all came to

miss hanging out in an old familiar place.

I kept returning to the club throughout the following decades. The

bands of the post-punk era—which, as I write this, are being rediscovered—

filled the gap left by those of us who were on tour. They pushed their music and performances further, too. Some of them really took the ball and ran

with it, making bands like ours seem tame by comparison. DNA, Bush Tet-

ras, and the Contortions brought newer and sometimes more radical musical

approaches to the club. In a way they kept the promise we had made. They

continued to make raw and innovative music, and for years, the club remained a place to catch waves of emerging musicians.

As time went on, and you could hear new bands at a variety of venues.

CBGB hung in there, and Hilly never entirely renovated or turned the place

into a tourist trap or a theme restaurant, bless his heart. (Though there

were rumors of a faux East Village to be built in Vegas that would include

a recreation of CB’s.) The place used to shock visitors and tourists who

expected some kind of imposing rock palace. CBGB doesn’t have grandeur,

but it was a place to hear what was bubbling up for quite a while. I remember seeing a wonderful band there in the mid-nineties, Cibo Matto, and then a

few weeks later seeing Chocolate Genius (Mark Anthony Thompson) in the

CBGB lounge next door. The club remained a vital place for a surprisingly

long time.

There was a period after that when I didn’t go there much, because the

music I was interested in was elsewhere. And then there was the whole trans-

formation of the Bowery and the surrounding area into a chic boho zone—a

change that spelled the end of those old places that weren’t pulling in lots of cash (except from the souvenir T shirts). I didn’t miss CB’s when it shut down—it wasn’t a vital place anymore, and the waves of nostalgia that were

being whipped up as its closing approached were a little obnoxious. There

were other clubs that had also fostered scenes, but that weren’t mourned

quite as strenuously—the original Knitting Factory, El Mocambo, Area, Don

Hill’s, and Hurrah’s, to name a few. I guess CB’s had a grittiness that made for a better story. I tried to help broker a deal between the building’s owner (a charity focusing on the homeless) and CB’s, but I could sense that nostalgia was overriding reason and that there would be no compromise.

DAV I D BY R N E | 263

C

D

The rules I’ve enumerated aren’t hard and fast. Think of them as guide-

lines that can steer you away from what might at first seem like obvious

or logical moves. One might, for example, think that making patrons pay rapt attention to the bands is key, but maybe it’s the exact opposite that fosters c h a p t e r n i n e

devotion to bands and musicians. What’s important is that local talent of

whatever type is given an outlet. Newer places in the New York area have

spawned scenes recently. I don’t know if the new venues follow all of my

Amateurs!

rules, but they are certainly relaxed places—you can hang out, and musicians come to hear other musicians. It’s a real testament to how much creativity

we all harbor that scenes emerge the way they do. People and neighborhoods

that were never suspected of being huge creative hubs—Detroit, Manchester,

Sheffield, Seattle—exploded when folks who didn’t even know they had it in

them suddenly blossomed and inspired everyone else around them.

266 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

c h a p t e r n i n e

Amateurs!

Music is made of sound waves that we encounter at specific

times and places: they happen, we sense them, and then

they’re gone. The music

experience

is not just those sound

waves, but the context in which they occur as well. Many

people believe that there is some mysterious and inher-

ent quality hidden in great art, and that this invisible substance is what causes these works to affect us as deeply as they do. This ineffable thing has not yet been isolated, but we do know that social, historical, economic, and psychological forces influence what we respond to—just a much as the work itself. The

arts don’t exist in isolation. And of all the arts, music, being ephemeral, is the closest to being an experience more than it is a thing—it is yoked to where you heard it, how much you paid for it, and who else was there.

The act of making music, clothes, art, or even food has a very different,

and possibly more beneficial effect on us than simply consuming those things.

And yet for a very long time, the attitude of the state toward teaching and

funding the arts has been in direct opposition to fostering creativity among the general population. It can often seem that those in power don’t want us to enjoy making things for ourselves—they’d prefer to establish a cultural hierarchy that devalues our amateur efforts and encourages consumption rather

than creation. This might sound like I believe there is some vast conspiracy DAV I D BY R N E | 267

at work, which I don’t, but the situation we find ourselves in is effectively the same as if there were one. The way we are taught about music, and the way

it’s socially and economically positioned, affect whether it’s integrated (or not) into our lives, and even what kind of music might come into existence

in the future. Capitalism tends toward the creation of passive consumers, and in many ways this tendency is counterproductive. Our innovations and creations, after all, are what keep many seemingly unrelated industries alive.

EATING CANNED SALMON BY A TROUT BROOK

In his book

Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music

, Mark Katz explains that prior to 1900, the aim of music education in America “was

to teach students how to

make

music.”1 The advent of the record player and recorded music in the early twentieth-century changed all that. I know what

you must be thinking—I am someone who to a large extent has made his liv-

ing off the sale and dissemination of my recordings; is it really possible that I believe that the way technology changed how we receive music wasn’t entirely a good thing for creative individuals like myself, or for us generally as a culture?

Of course people have always been able to go hear professional musi-

cians performing in big cities. Even in small towns, paid entertainers played at dances and weddings, as they still do in many parts of the world. Not all music was played by amateurs. But a hundred years ago most people didn’t

live in big cities, and for them music was made locally, often by friends and family. Many people likely had never heard an opera or a symphony. Maybe

A

a traveling group would pass through, but for the most part

people outside big cities had to be somewhat self-reliant when

it came to musical performance. (By the 1920s, a network of

ten thousand regional performance centers called Chautau-

quas had been established to serve as a way for people to hear

music and lectures brought in from other places.)A

Ellen Dissanayake, a cultural anthropologist and author of

Homo Aestheticus

, says that early on—she means

prehistori-

cally

early on—all art forms were communally made, which

had the effect of reinforcing a group’s cohesion and thereby

improving their chances of survival. In other words, writing

268 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

(storytelling), music, and art had a practical use, from an evolutionary perspective. Maybe, like sports, making music can function as a game—a musical

“team” can do what an individual cannot. Music-making imparts lessons that

reach well beyond songwriting and jamming.2

In the modern age, though, people have come to feel that art and music are

the product of individual effort rather than something that emerges from a

community. The meme of the solitary genius is powerful, and has affected the way we think about how our culture came into being. We often think that we

can, and even must rely on blessed individuals to lead us to some new place, to grace us with their insight and creations—and naturally that person is never us. This is not an entirely new idea, but the rise of commercially made recordings accelerated a huge shift in attitudes. Their promulgation meant that the more cosmopolitan music of folks who lived in the big cities (the music of