How Music Works (34 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

usually wrote the vocal melody and eventually the words. The musical bed

was, in these instances, very much collaborative.

NOTATION AND COMMUNICATION

There are not a lot of languages for describing and passing on music

outside of traditional notation—and even that method, though almost

universally accepted, sacrifices a lot. The same piece of written music can

sound completely different depending on who plays it. If Mozart could have

described in notation exactly how he intended every aspect of his composi-

tions to sound, there would be no need for multiple interpretations. When

musicians play together and record, they come up with terms—real and

invented—to try to communicate musical nuance. Funkier, more legato, more

holes and spaces, less pretty, spikier, simpler, pushed hard, more laid back—

I’ve said all of those things when trying to describe a musical direction or the feel I was looking for. Some composers resort to metaphors and analogies.

You could use food, sex, texture, or visual metaphors; I’ve heard that Joni

Mitchell described the kind of playing she wanted by naming colors. Then

there’s the shorthand of referring to other recordings, as Talking Heads did.

So, interpreting a written score, reading music notation, is itself a form of collaboration. The performer is remaking and in some ways rewriting the

piece every time he plays it. The vagueness and ambiguities of notation allow DAV I D BY R N E | 187

for this, and it’s not an entirely bad thing. A lot of music stays relevant thanks to the opportunities for liberal interpretation by new artists.

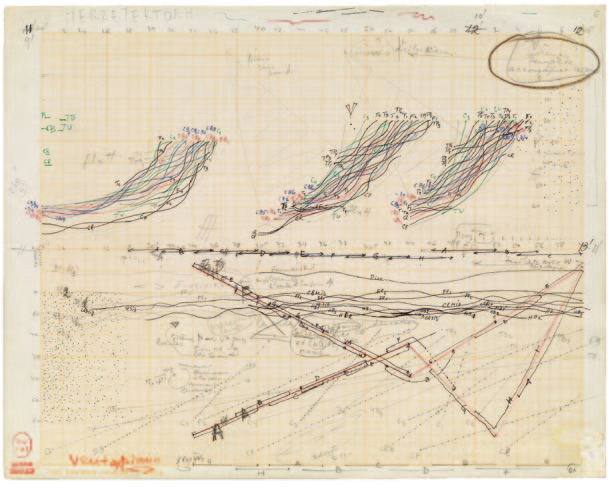

To encourage this kind of collaboration, to make the interpretive aspect

more overt, some composers have written their pieces as graphic scores. This is a way of granting a generous degree of freedom in the interpretation of

their work, while simultaneously suggesting and delimiting the organization, shape, and texture of their pieces across time. Below is one example, a graphic score by the composer Iannis Xenakis.A

This approach isn’t as crazy as it might seem. While these scores don’t

specify which notes to play, they do suggest higher or lower pitches as the

lines wander up and down, and they visually express how the players are to

relate to one another. This type of score views music as a set of organizing principles rather than a strict hierarchy—the latter viewpoint usually ends up

A

188 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

with melody at the top of the pile. It’s an alternative to the privileged position melody is usually given—it’s about texture, patterns, and interrelationships.

Robert Farris Thompson, a professor of art at Yale, pointed out that once

you let yourself see things this way, lots of things become “musical scores”—

although they might never have been intended to be played. He argued that

in a lot of African weaving, one can sense a rhythm. The repetition in these fabrics doesn’t consist of a simple looping of mirror images and patterns;

rather, modular parts recombine, shift position, and interact over and over

with one another, aligning in different ways over time, recombinant. They

are scores for a funky minimalist symphony. This musical metaphor implies

a kind of collaboration as well. While each color module in a quilt or textile is essential, no one part defines the whole the way we might define many

Western compositions by their dominant melody. Western compositions

can often be picked out—the melodies, at least—with one finger on a piano.

How would one pick out the “score” below in that way? There’s no dominant

motif or top line, though that doesn’t stop it from having a distinct identity.

It’s a neural network, a personality, a city, the Internet.

Below, on the left, is an African textile.B No surprise that later ver-

sions of these patterns, like the one pictured on the right, originated in

the New World.C There are musical breaks, fugues and stanzas, inversions

and recapitulations here. It’s not that crazy to believe that some part of the vast African musical sensibility was carried across the oceans and reconstructed using visual means—that these fabrics functioned as a structural

B

C

mnemonic aid. Perhaps they functioned as metaphors for how music could

be organized, which is also a lesson that can be applied to other parts of life.

I’m not suggesting that musicians sat down and “played” a quilt, but some

of the organizing sensibility might have been kept alive and transmitted by

such means.

If music can be regarded as an organizing principle—and in this case one

that places equal weight on melody, rhythm, texture, and harmony—then

we start to see metaphors everywhere we look. All kinds of natural phenom-

ena are “musical.” And I don’t mean they make sounds, but rather that they

organize themselves, and patterns become evident. Forms and themes arise,

express themselves, repeat, mutate, and then become submerged again. The

daily street ballet that Jane Jacobs wrote about, and the hustle and bustle

of an outdoor market, are each a kind of music. Stars, bugs, running water,

the chaotic tangle of vegetation. Musicians playing together find a kind of

symbiotic relationship between one another and an interplay between their

parts, so that the interlocking and interweaving create a sonic fabric.

How does this work? Let me share a few very different examples.

STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

A recent record of mine,

Everything That Happens Will Happen Today

, was pretty typical, as far as the collaborative process goes. Brian Eno, whom

I hadn’t worked with in more than twenty-five years, had a slew of largely

instrumental tracks on his shelf that seemed to want to become songs rather

than ambient tracks or film scores, but he was unhappy with his own attempts at completing them. He didn’t have much to lose by passing them to me—they

were just gathering dust (although I was told one did get passed to Coldplay), so unless I did something horrendous, which we agreed he could veto, it was a win-win situation.

As might be obvious by now, most contemporary collaborations, at least

the ones I do, don’t take place face-to-face anymore. They are the result of digital music files being shuttled back and forth via email or other Internet-based file-transfer formats. Does something get lost when the live aspect of collaboration disappears? Simple miscommunication can certainly spiral out

of control without the subtle signals we send through our facial expressions 190 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

and body language. And the encouragement, coaching, hyping, and prodding

that tends to happen in person—“Why not try this?” or “That’s great, but

what if you play it on a different instrument?”—may not happen, and cer-

tainly not as spontaneously.

That said, there are big advantages to the new protocol. If I can use a ping-pong analogy, with Internet exchanges one can wait overnight or longer to

return the serve, planning out what addition might work best, with no pres-

sure to come up with something brilliant on the spot. The breathing space is a luxury you don’t have when your collaborator is looking over your shoulder.

From Eno’s studio in London, I was sent stereo mixes of his musical ideas,

to which I added my vocal melodies and (eventually) lyrics without altering

his music beds in the least. Sometimes this made for some odd lyrical struc-

tures. On the song “The River,” Brian had a portion of what became a verse

repeat quite a few times—as if the song had gotten stuck, and couldn’t move

on. I accepted the challenge to write without straightening this peculiarity out—I knew that if it could be made to work, this unexpected variation in

structure might prevent the song from being too predictable. It worked, and

it added a kind of tension, as it delayed the musical resolution that came at the ends of verses. But just as often I slightly restructured his songs to bring them closer to a traditional form—repeating a section to create a place where a second verse could go, or nominating a “larger”-sounding section as a chorus, and then I might copy that, too, in order to make it recur again later in the song. However, I never even thought about requesting any substantial musical changes in the tracks, like key changes, or changes in groove or instrumentation. The unwritten rule in these remote collaborations is, for me, “Leave the other person’s stuff alone as much as you possibly can.” You work with what

you’re given, and don’t try to imagine it as something other than what it is.

Accepting that half the creative decision-making has already been done has

the effect of bypassing a lot of endless branching—not to mention a lot of

waffling and worrying. I didn’t ever have to think about what direction to

take musically—that train had already left the station, and my job was to

see where it wanted to go. This restriction on creative freedom turns out,

as usual, to be a great blessing. Complete freedom is as much curse as boon; freedom within strict and well-defined confines is, to me, ideal.

I listened to Eno’s instrumental tracks on and off, trying to get a sense

of the story the music was trying to tell. These tracks weren’t ambient, as

DAV I D BY R N E | 191

one might have expected from him, and I sensed that song structures might

emerge with just a little coaxing. “Emergence” is a popular term these days, but it almost perfectly evokes how musicians and songwriters cultivate the latent potential of a humble musical kernel. That’s why writers and musicians often say they feel only partially responsible for the creation of the works they’ve nurtured. They claim that the song, painting, dance piece, or words they’re

working on “tells” them what kind of thing it wants to become. But when that thing that is speaking to you originated with someone else, it’s sometimes

even more of a puzzle. Does it necessarily speak the same language as you? Is it sincere? Could their version be ironic instead? Is that clunky section supposed to be funny, or should you try to “fix” it? Do they want it to remain as beautiful and pretty as it seems, or would a little grit help?

Well, I didn’t exactly know at first what to make of Eno’s tracks. Maybe I had some trepidation working in the shadow of

Bush of Ghosts

, which after thirty years had amassed kind of a weighty reputation. I knew we couldn’t let ourselves do a

Bush of Ghosts II

. Music history is as much an influence on composition as anything else. After living with the tracks for almost a year, I eventually wrote Eno back. I told him the music inspired a sort of folk-electronic-gospel feeling, and suggested that my words and tunes might reflect this, and did that direction seem okay? Brian had discovered his love of gospel music years ago, and as he eventually wrote in the liner notes to

Everything That Happens

: