How Music Works (23 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

the phone company. People used them for gimmicks and special effects, but

these early developments did not have a wide musical influence. Soon enough, though, it became possible to grab or sample a whole bar of music, and though the samples were not of super-high quality, it was enough. Looping beats

became ubiquitous, and rhythm tracks made of sampled measures (or shorter

intervals) now function as the rhythm bed in many songs. You can “hear” the

use of Akai, Pro Tools, Logic, and other digital recording and sample-based

composition in most pop music written in the last twenty years. If you com-

pare recent recordings to many made in previous eras, you might not know

what makes them sound different, but you would certainly be able to hear it.

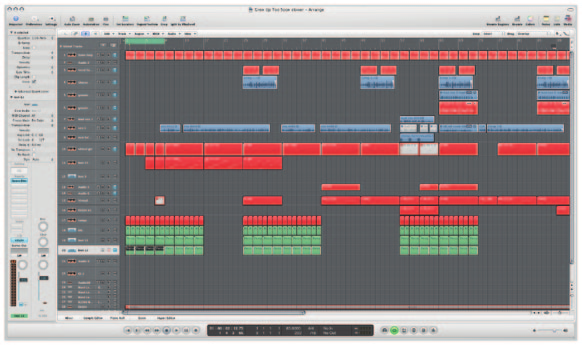

The effects the software has affected not just the sonic quality but also the composition process. Maybe you can also hear the effects of the ones and zeros that make up digital recording, though that may be less true as time goes by and technology passes the limits of the differentiating aspects of our hearing.

What you do hear, though, is a shift in musical structure that computer-aided composition has encouraged. Though software is promoted as being an unbiased tool that helps us do anything we want, all software has inherent biases that make working one way easier than another. With the Microsoft presentation software PowerPoint, for example, you have to simplify your presentations so much that subtle nuances in the subjects being discussed often get edited out. These nuances are not forbidden, they’re not blocked, but including them tends to make for a less successful presentation. Likewise, that which is easy to bullet-point and simply visualize works

better

. That doesn’t mean it actually

is

better; it means working in certain ways is simply easier than working in others. Music software is no different. Taking another avenue would make music

composition somewhat more tedious and complex.

An obvious example is quantizing. Since the mid-nineties, most popular

music recorded on computers has had tempos and rhythms that have been

quantized. This means that the tempo never varies, not even a little bit, and the rhythmic parts tend toward metronomic perfection. In the past, the tempos of recordings would always vary slightly, imperceptibly speeding up or

maybe slowing down just a little, or a drum fill might hesitate in order to

DAV I D BY R N E | 127

signal the beginning of a new section. You’d feel a slight push and pull, a tug and then a release, as ensembles of whatever type responded to each other and lurched, ever so slightly, ahead of and behind an imaginary metronomic beat.

No more. Now almost all pop recordings are played to a strict tempo, which

makes these compositions fit more easily into the confines of the recording

and editing software. An eight-bar section recorded on a “grid” of this type is exactly twice as long as a four-bar section, and every eight-bar section

is always exactly the same length. This makes for a nice visual array on the computer screen, and facilitates easy editing, arranging, and repairing as well.

Music has come to accommodate software, and I have to admit a lot has been

gained as a result. I can sketch out an idea for a song very quickly, for example, and I can cut and paste sections to create an arrangement almost instantly.

Severe or “amateurish” unsteadiness or poorly played tempo changes can be

avoided. My own playing isn’t always rock steady, so I like that those distracting flubs and rhythmic hiccups can be edited out. The software facilitates

all of this. But, admittedly, something gets lost in the process. I’m just now learning how to listen, value, and accommodate some of my musical instincts

that don’t always adhere to the grid. It makes things a little more complicated, as I still use the software, but I sense that the music breathes a little more as a result of me not always bending to what the software makes easiest.B

B

128 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

Sometimes, after having begun a songwriting process using computer

software, I find that I have to sing or play it apart from that recording to free myself from its straightening tendencies. In singing a song freely, for example, I might find that the note at the high point or at the end of a melodic arc

“wants” to hang on just a little bit longer than the grid of measures on the computer might indicate as normal. The result is that a verse might end up

being nine measures long, rather than the traditional eight. Alternately, a half measure might feel like a nice emotionally led extension, as well as giving a short, natural feeling breathing space, so then I’ll add that half measure to the grid on the software. In a recent collaboration with Fatboy Slim, I discovered that he often added “extra” measures to accommodate drum fills. It felt natural, like what a band would do. Shifting off the grid is sometimes beneficial in other ways, too. If a listener can predict where a piece of music is going, he begins to tune out. Shifting off an established pattern keeps things interesting and engaging for everyone, though it sometimes means you have to avoid the

path of least resistance that digital recording software often offers.

Quantizing, composing, and recording on a grid are just some of the

effects of software on music. Other effects are created by the use of MIDI,

which stands for musical instrument digital interface. MIDI is a software/

hardware interface by which notes (usually played on a keyboard) are encoded as a series of instructions rather than recorded as sounds. If you strike a

middle A on a keyboard, then the MIDI code remembers when that note was

played in the sequence of notes in the composition, how hard or quickly it

was struck, and how long it was sustained. What’s recorded is this infor-

mation and these parameters (a bit like a piano roll or the tines on a music box), but not the actual sound—so if that sequence of instructions is played back, it will tell the keyboard instrument to play that note and all the rest exactly when and how you played it previously. This method of “recording”

takes up much less computer memory, and it also means the instructional

information recorded is independent of the instrument played. Another

MIDI-equipped instrument with a completely different sound can be told

to play the same note, at the same time. What began as a piano sound might

be changed later to synthesizer strings or a marimba. With MIDI recording,

you can make arrangement decisions easily and at any time.

The way MIDI remembers how hard or fast you hit a note is by divid-

ing the speed of the note strike into 127 increments. The speed of your hit

DAV I D BY R N E | 129

will be rounded off so that it will fall somewhere in that predetermined

range. Naturally, if you strike a key faster, slower, or with more subtlety

than the MIDI software and its associated sensors can measure, then your

“expression” will not be accurately captured or encoded; it will be assigned the nearest value. As with digital recording, music gets rounded off to the

nearest whole number, under the assumption that finer detail would not be

discernible to the ear and brain.

There are instruments that can be used to trigger MIDI fairly well: key-

boards, some percussion pads, and anything that can be easily turned into

switches and triggers. But some instruments elude capture. Guitars aren’t

easily quantifiable in this way, nor are wind, brass, or most bowed string

instruments. So far, the nuances of those instruments have been just too

tricky to capture. Using MIDI therefore tends to entice people away from

using those instruments and the kinds of expression they are uniquely good

at. A lot of MIDI-based recordings tend to use arrays of sounds generated

or at least triggered by keyboards, so, for example, it’s easiest to play chord inversions that are keyboard friendly. The same chords on guitars tend to

have a different order of the same notes. Those keyboard chords, then, in

turn, incline composers to vocal melodies and harmonies that fit nicely with those specific versions of the chords, so the whole shape, melody, and arc of the song are being influenced, not just the MIDI parts and instruments. As

soon as technology makes one thing easier, it leaves a host of alternatives

in the dust.

The uncanny perfection that these recording and compositional technolo-

gies make possible can be pleasing. But metronomic accuracy can also be too

easy to achieve this way, and the facile perfection is often obvious, ubiquitous, and ultimately boring. Making repetitive tracks used to be laborious and time-consuming, and the slight human variations that inevitably snuck in as

a musician vainly attempted to be a machine were subliminally perceptible, if not consciously audible. A James Brown or Serge Gainsbourg track often consisted of a riff played over and over, but it didn’t sound like a loop. Somehow you could sense that it had been played over and over, not cloned. Imagine a row of dancers moving in unison—something that has a huge visceral impact.

Besides implying hard work, skill, and precision, it also works as a powerful metaphor. Now imagine that same row created by a series of mirror reflections or CGI technology. Not so powerful.

130 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

For many years, DJs, mixers, and hip-hop artists constructed tracks from

digital samples of riffs and beats taken from existing recordings. Some artists lifted entire hooks and choruses from pop songs and used them like a knowing reference or quote (P. Diddy does this a lot, as does Kanye West), the way you might quote a familiar refrain to a friend or lover to express your feelings. How many times has “put a ring on it” been used in conversation? Song references are like emotional shortcuts and social acronyms.

In much contemporary pop, if you think you’re hearing a guitar or piano,

most likely you’re hearing a sample of those instruments from someone else’s record. What you hear in such compositions are lots of musical quotations

piled on top of one another. Like a painting by Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Prince, or Kurt Schwitters made of appropriated images, ticket stubs, and bits of newspaper, this music is a species of sonic collage. In some ways it’s meta-music; music about other music.

However, many artists found out relatively quickly that when songs were

created in this way, they had to share the rights and profits with the original record companies and the original composers of those fragments and hooks.

Half of the money from a song often goes to the source of a hook or chorus. A few of my songs have been sampled in this way, and it’s flattering and fun to hear someone add a completely new narrative to something you wrote years

ago. The singer Crystal Waters sampled a Talking Heads song (“Seen and Not

Seen”—whoa, what a weird choice!) in her hit “Gypsy Woman (She’s Home-

less),” and that wonderful song of hers (which I even covered at one point)

bears no relation to the original. As far as I know, she or her producers were not intentionally referencing the original song; they simply found something about it, the way the groove felt or its sonic texture, useful.

Besides the fact that being sampled pays well, I don’t feel that it compro-

mises the original. Anyone can tell it’s a quote, a sample, right? Well, that depends. Trick Daddy, Cee Lo, and Ludacris used another Talking Heads song,

the demo “Sugar on My Tongue,” in their hit song “Sugar (Gimme Some).” In

that case the reference to the original was obvious, to me at least. They used our chorus hook for their own. But since that was never a popular Talking

Heads song (it was a demo included in a boxed set), that “quotation” aspect

was probably lost on most listeners. (For those keeping track, I did get paid and credited as a songwriter on that track, not a bad second life for what was originally a demo!) Since the song was already a bit of silly sexual innuendo, DAV I D BY R N E | 131

those guys taking it one step further was no big deal. But, if someone hypo-

thetically proposed repurposing the hook of a song I’d written as a new song about killing Mexicans, blowing up Arabs, or slashing women, I would say no.

Many artists soon began to find that the ubiquitous use of samples could

severely limit the income from “their” songs, which led many of them to

eventually stop or curtail their use of sampling technology. Sometimes even

what is easiest (grabbing a beat from a drum break on a CD, which only takes minutes) becomes a thing to be avoided. Bands like Beastie Boys picked up

instruments they’d put down years earlier, and hip-hop artists either dis-

guised their samples better, found more obscure ones, or, more often, began