How Music Works (13 page)

Authors: David Byrne

Tags: #Science, #History, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Art

It’s not as if one can shift music, visual art, dance, or spoken word like

pieces in a Tetris game until each art form plops into its perfect place, but it does give one the idea that some juggling of contexts might not hurt either.

I also realized that there were lots of unacknowledged theater forms going

on all around. Our lives are filled with performances that have been so woven into our daily routine that the artificial and performative aspect has slipped into invisibility. PowerPoint presentations are a kind of theater, a kind of aug-mented stand-up. Too often it’s a boring and tedious genre, and audiences

are subjected to the bad as well as the good. Failing to acknowledge that these are performances is to assume that anyone could and should be able to do it.

You wouldn’t expect anyone who can simply sing to get up on stage, so why

expect everyone with a laptop to be competent in this new theatrical form?

Performers try harder.

DAV I D BY R N E | 69

P

In political speeches—and I don’t think there’ll be any argument that they

are in fact performances—the hair, the clothes, and the gestures are all carefully thought out. Bush II had a team that did nothing but sort out the backgrounds behind the places where he would appear, the mission accomplished

banner being their most well-known bit of stagecraft. Same goes for public

announcements of all kinds: it’s all show biz, and that’s not a criticism. My favorite term for a certain new kind of performance is “security theater.” In this genre, we watch as ritualized inspections and patdowns create the illusion of security. It’s a form that has become common since 9/11, and even

the government agencies that participate in this activity acknowledge, off the record, that it is indeed a species of theater.

Performance is ephemeral. Some of my own shows have been filmed or

have appeared on TV and as a result they have found audiences that never

saw the original performances, which is great, but most of the time you

simply have to be there. That’s part of the excitement; it’s happening in

front of you, and in a couple of hours it won’t be there anymore. You can’t

press a button and experience it again. In a hundred years it will be a faint memory, if that.

There’s something special about the communal nature of an audience at

a live performance, the shared experience with other bodies in a room going

through the same thing at the same time, that isn’t analogous to music

heard through headphones. Often the very fact of a massive assembly of

fans defines the experience as much as whatever it is they have come to

see. It’s a social event, an affirmation of a community, and it’s also, in some small way, the surrender of the isolated individual to the feeling of belonging to a larger tribe. Many musicians make music influenced by this social

aspect of performance; what we write is, in part, based on what the live

experience of it might be. And the performing experience for the folks on

stage is absolutely as moving as it is for the audience, so we’re writing in the anxious hope of generating a moment for ourselves as much as for the

listener—it’s a two-way street. I love singing the songs I’ve written, espe-

cially in more recent performances, and part of the reason I decide to go

out and play them live is to have that experience again. Evolutionary biolo-

gist Richard Prum proposes that birds don’t just sing to attract mates and

to define their territory; they sometimes sing for the sheer joy of it. Like them, I have that pleasurable experience, and I seek out opportunities for

72 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

it. I don’t want to have it happen only once, in the recording studio, and

then have that moment get packed away, as a memory. I want to relive it, as

one can on stage, over and over. It’s kind of glorious and surprising that the catharsis happens reliably, repeatedly, but it does.

There’s an obvious narcissistic pleasure in being on stage, the center of

attention. (Though some of us sing even when there’s no one there.) In musi-

cal performances one can sense that the person on stage is having a good time even if they’re singing a song about breaking up or being in a bad way. For an actor this would be anathema, it would destroy the illusion, but with singing one can have it both ways. As a singer, you can be transparent and reveal yourself on stage, in that moment, and at the same time be the person whose story is being told in the song. Not too many other kinds of performance allow that.

DAV I D BY R N E | 73

c h a p t e r t h r e e

Technology

Shapes Music

c h a p t e r t h r e e

Technology

Shapes Music

The first sound recording was made in 1878. Since then, music

has been amplified, broadcast, broken down into bits, miked

and recorded, and the technologies behind those innovations

have changed the nature of what gets created. Just as photog-

raphy changed the way we see, recording technology changed

the way we hear. Before recorded music became ubiquitous, music was, for

most people, something we

did.

Many people had pianos in their homes, sang at religious services, or experienced music as part of a live audience. All those experiences were ephemeral—nothing lingered, nothing remained except for

your memory (or your friends’ memories) of what you heard and felt. Your

recollection could very well have been faulty, or it could have been influ-

enced by extra-musical factors. A friend could have told you the orchestra or ensemble sucked, and under social pressure you might have been tempted to

revise your memory of the experience. A host of factors contribute to making the experience of live music a far from objective phenomenon. You couldn’t

hold it in your hand. Truth be told, you still can’t.

As Walter Murch, the sound editor and film director, said, “Music was the

main poetic metaphor for

that which could not be preserved

.”1 Some say that this evanescence helps focus our attention. They claim that we listen more

closely when we know we only have one chance, one fleeting opportunity to

DAV I D BY R N E | 75

grasp something, and as a result our enjoyment is deepened. Imagine, as com-

poser Milton Babbitt did, that you could only experience a book by going to a reading, or by reading the text off a screen that displayed it only briefly before disappearing. I suspect that if that were the way we received literature, then writers (and readers) would work harder to hold our attention. They would

avoid getting too complicated, and they would strive mightily to create a memorable experience. Music did not get more compositionally sophisticated when it started being recorded, but I would argue that it did get texturally more complex. Perhaps written literature changed, too, as it became widespread—maybe it too evolved to be more textural (more about mood, technical virtuosity, and intellectual complexity than merely about telling a story).

Recording is far from an objective acoustic mirror, but it pretends to be

like magic—a perfectly faithful and unbiased representation of the sonic act that occurred out there in the world. It claims to capture exactly what we

hear—though our hearing isn’t faithful or objective either. A recording is also repeatable. So, to its promoters, it is a mirror that shows you how you looked at a particular moment, over and over, again and again. Creepy. However, such claims are not only based on faulty assumptions, they are also untrue.

The first Edison cylinder recorders weren’t very reliable, and the record-

ing quality wasn’t very good. Edison never suggested that they be used to

record music. Rather, they were thought of as dictation machines, something

that could, for example, preserve the great speeches of the day. The

New York

Times

predicted that we might collect speeches: “Whether a man has or has not a wine cellar he will certainly, if he wishes to be regarded as a man of taste, have a well-stocked oratorical cellar.”2

Please, try this fine Bernard Shaw or a rare

Kaiser Wilhelm II.

These machines were entirely mechanical. There was no electrical power

involved in either the recording or the playback, so they weren’t very loud compared to what we know today. To impress sound onto the wax, the voice or

instrument being recorded would get as close as possible to the wide end of the horn—a large cone that funneled the sound toward the diaphragm and then to

the inscribing needle. The sound waves would be concentrated and the vibrat-

ing diaphragm would move the needle, which incised a groove into a rotating

wax cylinder. Playback simply reversed the process. It’s amazing that it worked at all. As Murch points out, the ancient Greeks or Romans could have invented such a device; the technology wasn’t beyond them. For all we know, someone

76 | HOW MUSIC WORKS

at that time actually may have invented something similar and then abandoned it. Odd how technology and inventions come into being and fail to flourish for all sorts of reasons that have nothing to do with the skill, materials, or technology available at the time. Technological progress, if one can call it that, is full of dead ends and cul-de-sacs—roads not taken which could have led to

who knows what alternate history. Or maybe the meandering paths, with their

secret trajectories, would eventually and inevitably converge, and we’d all end up exactly where we are.

The wax cylinders that contained the recordings couldn’t be easily mass-

produced, so making lots of “copies” of these early recordings was an insane process. To “mass produce” these items, one had to set up an array of these

recorders as close as possible to the singer, band, or player—in other words, you could only produce the same number of recordings as you had recording

devices and cylinders running. To make the next batch, you’d load up more

blank cylinders and the band would have to play the same tune again, and so

on. There needed to be a new performance for every batch of recordings. Not

exactly a promising business model.

Edison set this apparatus aside for over a decade, but he eventually went

back to tinkering with it, possibly due to pressure from the Victor Talking

Machine Company, which had come out with recordings on discs. Soon he felt

he’d made a breakthrough. In 1915, when Edison demonstrated his new version

of an apparatus that recorded onto discs, he was convinced that now, finally, playback was a completely accurate reproduction of the speaker or singer being captured. The recording angel, the acoustic mirror, had arrived. Well, hearing those recordings, we might now think that he was somewhat deluded about

how good his gizmo was, but he certainly seemed to believe in it, and he managed to convince others too. Edison was a brilliant inventor, a great engineer, but also a huckster and sometimes a ruthless businessman. (He didn’t even

really “invent” the electric light bulb—Joseph Swan in England had made them previously, though Edison did establish that tungsten would be the great long-lasting filament for that device.) And he usually managed to market and pro-

mote the hell out of his products, which certainly counts for something.

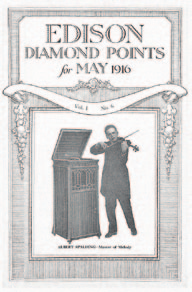

These new Diamond Disc Phonographs were promoted via what Edison

referred to as Tone Tests. There is a promo film he made called

The Voice of the

Violin

(oddly, for something promoting a sound recorder, it was a silent film) that helped publicize the Tone Tests. Edison was marketing and selling the

DAV I D BY R N E | 77