How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas (24 page)

Read How Mrs. Claus Saved Christmas Online

Authors: Jeff Guinn

“I hear he thinks his Puritan masters in London will be angry if people here do the usual things on the holiday,” Janie confided one weary day as I lugged water buckets into the washing shed. Occasionally I still had to perform this backbreaking chore. “You know, Laylaâthe feasting, and the singing in the streets, and all that. He'd like to impress them with his control of the city by making sure that doesn't happen.”

“I don't really see how he can prevent it,” I replied. “There are no laws against celebrating Christmasâat least, not yet.”

“He'll try to find a way,” Janie predicted, and she was right. Only a few days later, town criers began walking around Canterbury's streets urging people “at the suggestion of our beloved mayor” to treat Christmas like an ordinary day. Shops should remain open. Everyone should go to work. If the savior's birth must be celebrated at all, it should be with a moment's silent meditation. No gifts, either, because that was only continuing a pagan tradition.

“Are Christmas gifts really bad, Auntie Layla?” Sara wanted to know after listening to the criers.

“Not at all, my darling,” I said. “Gifts anytime are simply a token of love and caring, and gifts at Christmas are meant to add joy to a wonderful celebration. Please remember that the kind thoughts of the giver are even more important than the gift, and then you'll have the perfect spirit of Christmas.”

Christmas fell on a weekday that year, and on the Saturday before Margaret Sabine called her servants together to tell us we would be expected to report to work as usual on December 25.

“I know some of you may disagree with my husband'sâthat is to say, my

family's

âposition on Christmas, which is more properly called Christ-tide, but that is just too bad,” she said. “Those who do not report for work will have to find employment somewhere else, and there are few other jobs to be had in Canterbury right now. And if any of you have any thoughts of the usual caroling at our home with drinks and food provided for all, forget them. We are a godly Puritan household and will no longer honor drunken, pagan traditions.”

family's

âposition on Christmas, which is more properly called Christ-tide, but that is just too bad,” she said. “Those who do not report for work will have to find employment somewhere else, and there are few other jobs to be had in Canterbury right now. And if any of you have any thoughts of the usual caroling at our home with drinks and food provided for all, forget them. We are a godly Puritan household and will no longer honor drunken, pagan traditions.”

No one dared argue, most because they knew Margaret Sabine would certainly fire them for disobeying, and me because my husband and his companions had long ago decided to always respect the beliefs of others. If the Sabines did not want Christmas celebrated in their home, it should not be. But the rest of us could certainly do as we wished in

our

homes.

our

homes.

So eight-year-old Sara woke up on the morning of December 25, 1642, to discover a dress and a doll by her pallet, as well as several candy canes on her pillow. She shrieked with delight, trying to pull the dress on over her nightgown while cuddling the doll at the same time. As soon as those contradictory tasks were accomplished, she jammed a candy cane in her mouth, mumbling in wonder over the shape, color, and taste.

“And just last night she was privately asking me to tell her the truth about Father Christmas,” Elizabeth confided. “Sophia told her they were too old to believe in some made-up Catholic saint.”

“Sophia was wrong,” I said, and handed a candy cane to Elizabeth, who liked it very much. Leonardo had sent along dozens, so I had plenty. When Sara was sufficiently calm, we fed her breakfast and walked to town and our jobs at the Sabines. Sara reported later that, despite Sophia's parents telling everyone else not to celebrate the holiday, they had given Sophia dozens of Christmas gifts, though Sara much preferred her own doll and dress and candy to anything her friend had received. When the day's work was over, Sara and Elizabeth and I walked hand-in-hand back to the cottage, softly singing Christmas carols. Later, we ate goose and mince pie, both special, once-a-year treats, and only after I climbed into the loft bed I shared with Sara did I realize with a start that not once during the whole day had I even thought about my usual magical gift-giving.

Though the working people in town reluctantly obeyed the Sabines' edict not to come to their fine home for caroling and treats, most of them openly defied their mayor's wishes and celebrated Christmas as best they could. The shops in town that Sabine didn't own were shuttered in honor of the holiday. His remained open, but had few customers. The town's non-Puritan churches held worship services, and the grandest of these was in the fine Canterbury Cathedral. Because we had to work, Elizabeth and I were unable to attend, though we badly wanted to. Well, we told ourselves, we had kept Christmas as best we could, with joy and gifts to celebrate the birth of Jesus.

“Sophia says her father is afraid his reputation has suffered because so many people here kept to their Christmas traditions when he asked them not to,” Sara told us a few days later. “She says he wrote to someone in London asking for help.”

“What sort of help?” Elizabeth asked absently. Sophia talked about so many things it was impossible to know what was important and what wasn't.

“Just help, Sophia said.”

At dawn on the second Sunday in January 1643, there were loud shouts outside the cottage. “Someone's destroying the cathedral,” a man bellowed, and Elizabeth, Sara, and I quickly pulled on our clothes and ran with the rest into town. What we saw there was horrifying. A number of men with heavy clubs, some high on ladders, were smashing the cathedral's lovely stained-glass windows, howling, “Death to Christmas!” Dozens of others, dressed in full Roundhead armor, stood pointing muskets at the dismayed crowd.

“The mayor called in troops!” someone said, and it was true. Avery Sabine stood safely inside the line of soldiers holding everyone at gunpoint, his arms folded as he watched the destruction of the church windows with every appearance of satisfaction.

“It's horrible, Auntie Layla,” Sara whispered to me. Elizabeth and I held her tight between us. Then my own blood ran even colder, because one of the stick-wielding men broke away from his terrible work and walked to Avery Sabine's side. In the early morning light, I could see that his cloak was a color other than traditional Puritan black.

Blue Richard Culmer turned to the crowd and shouted, “Your mayor told you not to celebrate Christmas. You should have listened!” As in London, his lips split wide in a happy leer while his eyes remained dark and joyless. “If you do it again next year, we'll break you like we broke these sinful windows!” Then, with an animal-like howl of triumph, he signaled for the club-wielders and musketmen to march back toward London through the West Gate while Avery Sabine preened solemnly and almost everyone else stood numb with despair.

“Don't test me on Christmas again,” Sabine said to the stunned crowd, and walked back to his fine house.

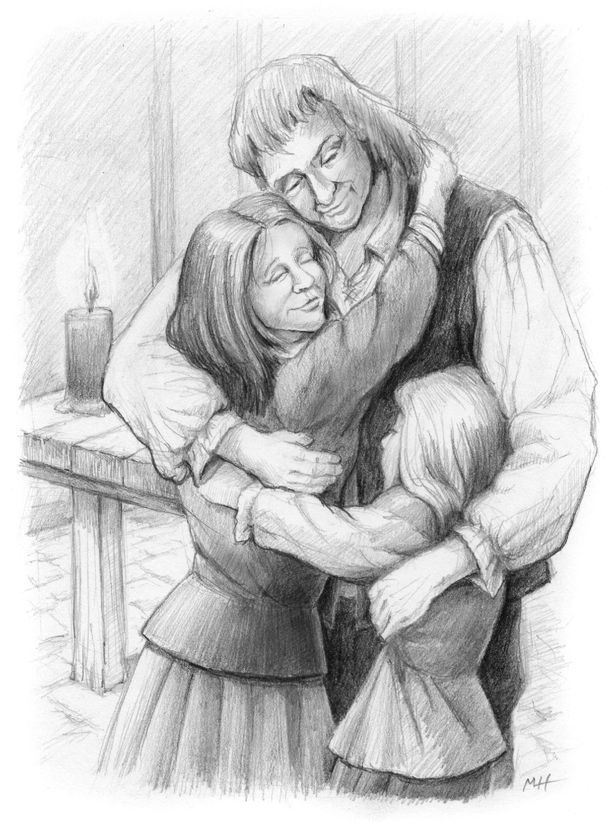

Elizabeth, Sara, and I returned one night from work to find there were candles already lit in the cottage. Both mother and daughter knew what this must mean and ran shouting through the door. I followed, and found them wrapped in the arms of a tall, wide-shouldered man who nodded briefly in my direction before burying himself back in this joyful three-person embrace.

CHAPTER

Fourteen

Fourteen

Â

Â

Â

Â

T

he Christmas-loving people of Canterbury were terribly shaken by the assault on their cathedral, just as Avery Sabine and Blue Richard Culmer intended. A few brave souls boarded up the gaping holes in the sandstone walls where the stained-glass windows had sparkled and inspired for centuries, but no one suggested new windows should be installed. In the moment the original windows were shattered, so too was the resolve of some in Canterbury to keep celebrating Christmas no matter what the mayor and his Puritan masters had to say about it.

he Christmas-loving people of Canterbury were terribly shaken by the assault on their cathedral, just as Avery Sabine and Blue Richard Culmer intended. A few brave souls boarded up the gaping holes in the sandstone walls where the stained-glass windows had sparkled and inspired for centuries, but no one suggested new windows should be installed. In the moment the original windows were shattered, so too was the resolve of some in Canterbury to keep celebrating Christmas no matter what the mayor and his Puritan masters had to say about it.

“I doubt there'll be many around here welcoming Father Christmas from now on,” Janie suggested as we wrung out tablecloths in the washing shed. It was the spring of 1643, and I had been employed by the Sabines long enough that I was no longer the newest servant. Much of my time was spent indoors, where the work was easier. Melinda, hired soon after the assault on the cathedral, now had the dubious honor of always being assigned the hardest chores, which included water hauling. But there was a lot of washing to be done on this particular day, and I had been instructed to go out and help.

“No act, no matter how terrible, can destroy Christmas,” I replied. “Somehow, the holiday will prevail.”

Sometimes, though, I wondered, especially when, over the next months, the Roundheads won a series of victories over King Charles and his army. Oliver Cromwell had returned with properly trained cavalry, and his troops were instrumental in winning several battles. There were rumors the king might now be willing to negotiate a settlement that would allow him to remain on the throne in return for certain concessions, which would give more power to Parliament. In general, I simply hated the whole idea of civil war, and hoped it would end as quickly as possible. But I also knew men like Blue Richard Culmer would never really compromise about anything, although they might pretend to for a time. If Parliament defeated the king, the Puritans would find ways to dominate Parliament, and, eventually, force their beliefs on everyone else in England.

By late summer, the Scots had allied themselves with the Roundheads, and the king's forces gradually lost control of their few ports. Avery Sabine strutted down the streets of Canterbury, and was often called away to London on mysterious business, which Sophia told Sara her father would not even discuss with his family, though he promised his wife and daughter that great things were in store.

“He sometimes mentions Christmas, and laughs when he does,” Sara reported. “Sophia says I should throw away that doll Father Christmas left me, but I won't.”

In September 1643, just after the king's forces suffered a terrible defeat at Newbury, Alan Hayes came home from his long voyage. Elizabeth, Sara, and I returned one night from work to find there were candles already lit in the cottage. Both mother and daughter knew what this must mean and ran shouting through the door. I followed, and found them wrapped in the arms of a tall, wide-shouldered man who nodded briefly in my direction before burying himself back in this joyful three-person embrace. I went outside for a little while, to give the reunited family some privacy, and wondered what I would do if Alan Hayes did not want a houseguest who had already been living in his home for more than a year.

It turned out I had no cause for concern. After about ten minutes, Sara came to fetch me, saying her father very much wanted to meet his wife's cousin.

“If Elizabeth and Sara love you, then so do I,” Alan proclaimed, and by the time we had finished dinnerâeggs from a neighbor's chicken made up the main courseâAlan was insisting I stay as long as I liked, “up to and including forever.” Actually, I had no idea of how long I wanted to remain in Canterbury, or even in England. If the Roundheads wonâit now seemed possible they mightâthen Christmas would soon be abolished. Avery Sabine and Blue Richard Culmer had demonstrated the lengths to which the Puritans would go to frighten people into giving up the holiday. If England had no Christmas, there was no longer any reason for Arthur and Leonardo to operate the toy factory in London, and certainly no reason for me to delay any longer my reunion with my husband, whom I now had not seen in twenty-three years. True, for ageless gift-givers like Nicholas and me, twenty-three years was the merest hiccup of time, but I still missed him so very much, and knew he missed me equally.

Alan Hayes

But somehow I believed I must stay where I was. Arthur, certainly, thought I should get out of England immediately. He said as much when, in November 1643, he came to Canterbury to see me.

“I decided this couldn't be communicated as effectively in a letter, Layla,” Arthur said. We were off in the hills outside Canterbury on a late Saturday afternoon, out of sight in a grove of trees so no passing neighbors might start wondering aloud to their friends about the stranger visiting Alan and Elizabeth's longtime guest. “We hear constantly at the toy factory in London that Parliament is determined to eradicate Christmas and everything about it. Blue Richard Culmer grows more powerful each day. I doubt he's forgotten youâsuch men remember everyone they consider to be their enemies. The Roundheads now control almost every port city, but we can find some way to get you through. Go back to Nuremberg, or, better, across the ocean to join Nicholas and Felix. But leave Englandâ

now.

”

now.

”

Other books

Tattoos & Teacups by Anna Martin

Don't Look Away (Veronica Sloan) by Kelly, Leslie A.

Six Feet From Hell: Crisis by Coley, Joseph

The Loner: Dead Man’s Gold by Johnstone, J.A.

In The End (Butterfly #1) by Isabella Redwood

Plain Jane by Fern Michaels

Real Murder (Lovers in Crime Mystery Book 2) by Lauren Carr

This Northern Sky by Julia Green

Deadly Desserts (Sky High Pies Cozy Mysteries Book 6) by Mary Maxwell