How Hitler Could Have Won World War II (36 page)

At last on January 8, 1945, Hitler agreed to a limited withdrawal from the tip of the Bulge. Inexorably, the retreat continued. By January 28, the German lines were back approximately where they had been when the offensive started.

Among 600,000 Americans eventually involved in the battle of the Bulge, casualties totaled 81,000, of whom 15,000 were captured and 19,000 killed. Among 55,000 British involved, casualties totaled 1,440, of whom 200 were killed. The Germans, employing close to 500,000 men, lost at least 100,000 killed, wounded, or captured. Each side forfeited about 800 tanks, and the Luftwaffe lost a thousand aircraft.

The Americans could make good their losses in short order, the Germans could not replace theirs. All that Adolf Hitler achieved at this terrible cost was to delay the Allied advance in the west by a few weeks. But it actually assured swift success for the Red Army advancing in a renewed drive in the east. In the end, the battle of the Bulge probably speeded up Germany's collapse.

24 THE LAST DAYS

THE RED ARMY HAD BEEN STALLED ALONG THE VISTULA RIVER IN POLAND SINCE autumn 1944. Its astonishing advances during the summer had come to a standstill because the vastly overextended Russian supply line finally snapped. Red Army commanders held up the final assault on Nazi Germany until the railways behind the front could be repaired and converted to the Russian wider-gauge track.

Once done, the Soviets accumulated abundant supplies along the entire front and reconstituted their armies. By early 1945 they had assembled 225 infantry divisions and twenty-two armored corps between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains. Soviet superiority was eleven to one in infantry, seven to one in tanks, and twenty to one in artillery and aircraft. Most important was the great quantity of American trucks delivered to the Russians by Lend-Lease. Trucks transformed a large part of the Red Army into motorized divisions able to move quickly around the Germans, whose mobility was shrinking by the day due to extreme shortages of fuel.

When Heinz Guderian, army chief of staff, presented the figures of Soviet strength, Hitler exclaimed, “It's the greatest imposture since Genghis Khan! Who is responsible for producing all this rubbish?”

Hitler had not used the long stalemate in the east to build a powerful defensive line of minefields and antitank trapsâsuch as Erwin Rommel had urged immediately after the battle of Kursk in 1943. His defensive system remained what it had been all along: each soldier was to stand in place and fight to the last round. He refused even a timely step back to avoid the full shock of a Soviet attack. The Russians were well aware of the hopeless weakness of Hitler's “hold-at-all-costs” policy, and were prepared to exploit it.

On December 24, 1944, Guderian met with Hitler and his staff and pleaded with them to abandon the Ardennes offensive and move every possible soldier eastward to shield against the Soviet attack.

The heart of continued German resistance, Guderian emphasized, was the industrial region of upper Silesia (about fifty miles west of Cracow around Katowice and Gliwice). The German armaments industry had already been moved there, and it was beyond the range of American and British bombers. The Ruhr, on the other hand, was paralyzed by bombing attacks.

“The loss of upper Silesia must lead to our defeat within a very few weeks,” Guderian said.

It was no use. Hitler insisted that continued attacks in the west would eventually cripple the western Allies. Furthermore, he rejected Guderian's request to evacuate by sea the army group (of twenty-six divisions) now isolated in Courland in western Latvia. And while Guderian was en route back to his headquarters near Berlin, Hitler transferred two SS panzer divisions from the Vistula to Hungary with the task of relieving the siege of Budapest. This left Guderian with a mobile reserve of just twelve divisions to back up fifty weak infantry divisions holding a front 750 miles long.

“The eastern front is like a house of cards,” Guderian told Hitler on January 9. “If the front is broken through at one point all the rest will collapse.” But Hitler merely responded: “The eastern front must help itself and make do with what it's got.”

Hitler also turned down requests of field commanders that German civilians be evacuated from East Prussia and other regions likely to be overrun by the Russians. He said evacuation would have a bad effect on public opinion.

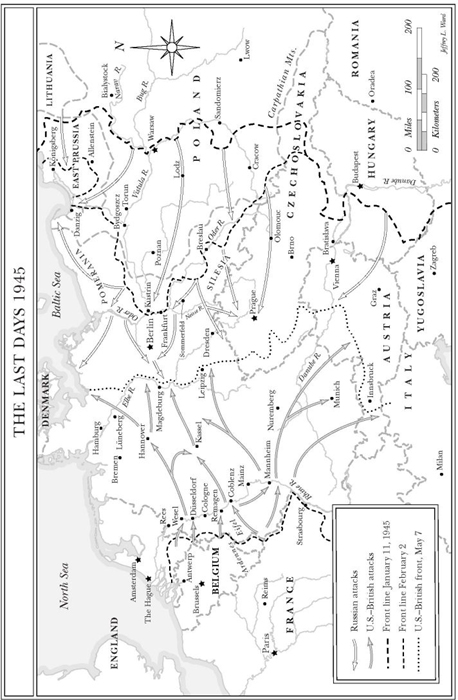

When the Soviet offensive burst across the Vistula on January 12, 1945, the Red Army commanders had their eyes set on Berlin, 300 miles west of Warsaw. This was to be the final drive to destroy Nazi Germany.

The first assault came by seventy Soviet divisions of I. S. Konev's 1st Ukrainian Front across the Vistula out of a bridgehead near Baranov, 120 miles south of Warsaw. Artillery pulverized the Germans, and in three days the Red soldiers had broken entirely through their defenses, captured Kielce, and were pouring over the Polish plain in an expanding torrent.

Two days later G. K. Zhukov's 1st White Russian Front burst out of bridgeheads around Magnuszev and Pulawy, 75 miles south of Warsaw, while K. K. Rokossovsky's 2nd White Russian Front stormed across the Narev north of Warsaw. Zhukov's divisions wheeled north to surround Warsaw, while Rokossovsky's troops blew apart the German defenses covering the southern approach to East Prussia, creating a breach 200 miles wide. Altogether 200 Soviet divisions were now rolling westward.

Chaos descended on the Nazi high command. Hitler, more and more ignoring reality, returned to Berlin on January 16 from his Eagle's Aerie east of the Rhine. The marble halls of the Chancellery were in ruins from bombing, but the underground bunker fifty feet below remained operational. At long last, Hitler decided that the armies in the west had to go over to the defensive to make forces available to stem the Russian tide. He immediately ordered 6th Panzer Army to move eastward.

Guderian was delighted, and planned to use the army to attack the flanks of the Soviet spearheads in Poland to slow their advance. He learned, however, that Hitler was sending 6th Panzer Army to Hungary to assist in relieving the siege of Budapest.

“On hearing this I lost my self-control and expressed my disgust to Jodl in very plain terms,” Guderian wrote. But he could not change Hitler's mind.

On January 17 the General Staff operations section reported that Soviet forces were about to surround Warsaw, and proposed a new defensive line to the west. Guderian agreed, and ordered the small city garrison to withdraw at once. When informed, Hitler insisted that Warsaw be held at all costs. The garrision commander, however, ignored Hitler's command and withdrew his battalions. Hitler flew into a rage, and thought of nothing the next few days but how to punish the General Staff.

Guderian protested that he had made the decision, but Hitler replied: “No, it's not you I'm after, but the General Staff. It is intolerable to me that a group of intellectuals should presume to press their views on their superiors.”

Hitler arrested a colonel and two lieutenant colonels in the operations section. Guderian demanded an inquiry, and two Gestapo agents interrogated him for days. These interrogations squandered Guderian's time and nervous energy at a time when a battle for life or death was being fought on the eastern front. Guderian got two of the officers released, but the third remained in a concentration camp till the end of the war.

On January 25 Guderian tried to get Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to convince Hitler to seek an armistice on the western front, while continuing to fight the Russians in the east. Ribbentrop replied that he did not dare approach the Fuehrer on the subject. As Guderian departed, Ribbentrop said, “We will keep this conversation to ourselves, won't we?” Guderian assured him he would do so. But Ribbentrop tattled to Hitler, and that evening the Fuehrer accused Guderian of treason.

Meanwhile Russian forces continued to advance on all fronts, reaching the German frontier in Silesia on January 19, and soon overrunning upper Silesia. Zhukov's troops captured Lodz, bypassed Posen (Poznan), crossed the German frontier, and on January 31 reached the lower Oder River near Küstrin (now Kostryzh)âforty miles from Berlin. Only 380 miles separated the Russians from the advanced positions of the western Allies.

At the same time, Rokossovsky gained the southern gateway to East Prussia at Mlawa and drove on to the Gulf of Danzig, isolating German forces in East Prussia. These fell back into Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), where Russians besieged them.

The virtually unchecked advance of the Red Army set off the frantic flight of most German civilians toward the west. The flood of refugees jammed roads, created chaos, and made troop movements all the more difficult.

Hitler's final divorce from reality came now. With the Ruhr bombed into rubble and upper Silesia occupied, Albert Speer, Nazi armaments chief, sent a memorandum to Hitler that began: “The war is lost.” Hitler read the first sentence and locked the memo in his safe. Speer requested a private interview to explain Germany's desperate straits. But the Fuehrer declined, telling Guderian: “I refuse to see anyone alone anymore. Any man who asks to talk to me alone always does so because he has something unpleasant to say to me. I can't bear that.”

The Red Army was outrunning its supplies, and a thaw in the first week of February braked supplies further by turning roads into quagmires, while the ice broke up on the Oder, increasing its effect as an obstacle. Guderian scraped up what troops he could find. These stopped the Russians with only shallow bridgeheads over the Oder near Küstrin and Frankfurt-an-der-Oder.

Meantime Konev in Silesia extended bridgeheads north of Breslau (now Wroclaw), swept north down the left or western bank of the Oder, and on February 13 reached Sommerfeld (now Lubsko). This same day Budapest fell at last; Hitler's attempt to relieve it had failed. The surrender yielded 110,000 prisoners to the Russians. On February 15, Konev's troops advanced to the Neisse River, near its junction with the Oder, and came level with Zhukov's forces.

By the third week of February the front in the east was stabilized, with the aid of reinforcements brought from the west and the interior. The crisis posed by the Russian menace led to Hitler's decision that defense of the Rhine had to be sacrificed to holding the Oder.

Hitler diverted the major part of his remaining forces to the east, still believing that the western Allies were unable to resume the offensive because of losses in the Ardennes. He turned his V-1s and V-2s on Antwerp, in hopes of stopping the arrival of Allied supplies. In all, the Germans hurled 8,000 V-weapons at Antwerp and other targets, but the damage they did was negligible.

Eisenhower's armies, now eighty-five divisions strong, prepared to close in on the Rhine. Hitler refused to withdraw forces behind this river barrier. Consequently, the Allies had only to break through the thin crust of front-line defenses to open wide avenues of advance into the German rear.

Eisenhower, to the disgust of American senior commanders, assigned the main striking force to Montgomery's 21st Army Group in the north, adding the U.S. 9th Army to Montgomery's British 2nd and Canadian 1st Armies. Montgomery planned another of his meticulously slow, overwhelming assaultsâthis time over the Rhine in the vicinity of Wesel, opposite Holland.

Even so, Bradley's U.S. 1st and 3rd Armies were far stronger than the German forces facing them, and on March 7, 1945, George Patton's 3rd Army broke through the Schnee Eifel Mountains east of the Ardennes and, in three days, reached the Rhine near Coblenz. The same day farther north the 9th Armored Division of 1st Army found a gap and raced through to the Rhine so quickly that the Germans did not have time to blow the railroad bridge at Remagen, near Bonn.

American engineers frantically cut every demolition wire they could find, while a platoon of infantry raced across the bridge. As they neared the east bank, two charges went off. The bridge shook, but stood. Tanks rushed over the span, and by nightfall the Americans had a strong bridgehead on the east bank.

When Hodges called Bradley with the news, Bradley responded: “Hot dog, Courtney, this will bust him wide open!”

Bradley told Hodges to pour every man and weapon possible across the bridge and strike for the heart of Germany. But Harold R. (Pink) Bull, Eisenhower's chief of operations, said no. “You're not going anywhere down there at Remagen,” he announced. “You've got a bridge, but it's in the wrong place. It just doesn't fit the plan.”

The “plan”âagreed to by Eisenhowerâwas for Montgomery to launch his grand attack at Wesel on March 24, three weeks later.

Bradley was furious, and finally got Eisenhower to approve a strike out of the Remagen bridgehead toward Frankfurt with five divisions. Meanwhile Patton cleared the west bank of the Rhine between Coblenz and Mannheim, cutting off all German forces still to the west by March 21. The Germans lost 350,000 men, the vast bulk of them captured.

On March 22, Patton's troops crossed the Rhine almost unopposed at Oppenheim, between Mainz and Mannheim. When the news reached Hitler, he learned that only five tank destroyers were available to contest the advance of an entire American armyâand they were a hundred miles away.