Goliath (4 page)

He was the only person on the airship who knew what she really was, and he generally took care not to mention it aloud.

“What do you want?” she said quietly.

He didn’t look up at her, but instead fussed with his breakfast as if this were a friendly chat. “I’ve noticed the crew seems to be preparing for something.”

“Aye, we got a message this morning. From the czar.”

Volger looked up. “The czar? Are we changing course?”

“That’s a military secret, I’m afraid. No one knows except the officers.” Deryn frowned. “And the lady boffin, I suppose. Alek asked her, but she wouldn’t say.”

The wildcount scraped butter onto his half soggy toast, giving this a think.

During the month Deryn had been hiding in Istanbul, the wildcount and Dr. Barlow had entered into some sort of alliance. Dr. Barlow made sure he was kept up with news about the war, and Volger gave her his opinions on Clanker politics and strategy. But Deryn doubted the lady boffin would answer this question for him. Newspapers and rumors were one thing, sealed orders quite another.

“Perhaps

you

could find out for me.”

“No, I couldn’t,” Deryn said. “It’s a military secret.”

Volger poured coffee. “And yet secrets can be

so

difficult to keep sometimes. Don’t you think?”

Deryn felt a cold dizziness rising up inside, as it always did when Count Volger threatened her. There was something

unthinkable

about everyone finding out what she was. She wouldn’t be an airman anymore, and Alek would never speak to her again.

But this morning she was not in the mood for blackmail.

“I can’t help you, Count. Only the senior officers know.”

“But I’m sure a girl as resourceful as you, so obviously adept at subterfuge, could find out. One secret unraveled to keep another safe?”

The fear burned cold now in Deryn’s belly, and she almost gave in. But then something Alek had said popped into her head.

“You can’t let Alek find out about me.”

“And why not?” Volger asked, pouring himself tea.

“He and I were just in the rookery together, and I almost told him. That happens sometimes.”

“I’m sure it does. But you

didn’t

tell him, did you?” Volger tutted. “Because you know how he would react. However fond you two are of each other, you are a commoner.”

“Aye, I know that. But I’m also a soldier, a barking good one.” She took a step closer, trying to keep any quaver out of her voice. “I’m the very soldier Alek might have been, if

he hadn’t been raised by a pack of fancy-boots like you. I’ve got the life he missed by being an archduke’s son.”

Volger frowned, not understanding yet, but it was all coming clear in Deryn’s mind.

“I’m the boy Alek wants to be, more than anything. And you want to tell him that I’m really a

girl

? On top of losing his parents and his home, how do you think he’ll take that news, your countship?”

The man stared at her for another moment, then went back to stirring his tea. “It might be rather . . . unsettling for him.”

“Aye, it might. Enjoy your breakfast, Count.”

Deryn found herself smiling as she turned and left the room.

As the great jaw of the cargo door opened, a freezing

whirlwind spilled inside and leapt about the cargo bay, setting the leather straps of Deryn’s flight suit snapping and fluttering. She pulled on her goggles and leaned out, peering at the terrain rushing past below.

The ground was patched with snow and dotted with pine trees. The

Leviathan

had passed over the Siberian city of Omsk that morning, not pausing to resupply, still veering northward toward some secret destination. But Deryn hadn’t found time to wonder where they were heading; in the thirty hours since the imperial eagle had arrived, she’d been busy training for this cargo snatch-up.

“Where’s the bear?” Newkirk asked. He leaned out past her, dangling from his safety line over thin air.

“Ahead of us, saving its strength.” Deryn pulled her gloves tighter, then tested her weight against the heavy

cable on the cargo winch. It was as thick as her wrist—rated to lift a two-ton pallet of supplies. The riggers had been fiddling with the apparatus all day, but this was its first real test. This particular maneuver wasn’t even in the

Manual of Aeronautics

.

“Don’t like bears,” Newkirk muttered. “Some beasties are too barking

huge

.”

Deryn gestured at the grappling hook at the end of the cable, as big as a ballroom chandelier. “Then you’d best make sure not to stick that up the beastie’s nose by accident. It might take exception.”

Through the lenses of his goggles, Newkirk’s eyes went wide.

Deryn gave him a punch on the shoulder, envying him for his station at the business end of the cable. It wasn’t fair that Newkirk had been gaining airmanship skills while she and Alek had been plotting rebellion in Istanbul.

“Thanks for making me even

more

nervous, Mr. Sharp!”

“I thought you’d done this before.”

“We did a few snatch-ups in Greece. But those were just mailbags, not heavy cargo. And from horse-drawn carriages instead of off the back of a barking great bear!”

“That does sound a bit different,” Deryn said.

“Same principle, lads, and it’ll work the same way,” came Mr. Rigby from behind them. His eyes were on his

pocket watch, but his ears never missed a thing, even in the howling Siberian wind. “Your wings, Mr. Sharp.”

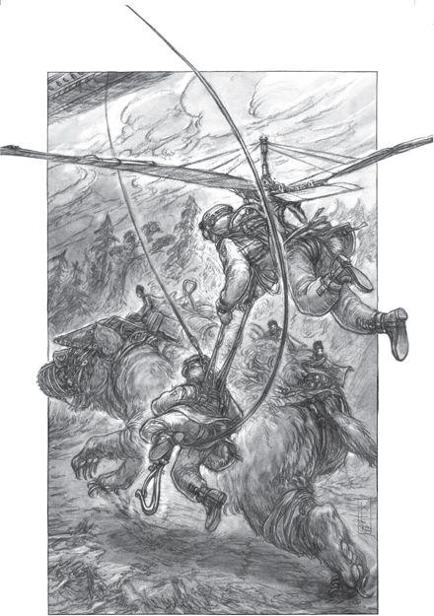

“Aye, sir. Like a good guardian angel.” Deryn hoisted the gliding wings onto her shoulders. She would be carrying Newkirk, using the wings to guide him over the fighting bear.

Mr. Rigby signaled to the winch men. “Good luck, lads.”

“Thank you, sir!” the two middies said together.

The winch began to turn, and the grappling hook slid down toward the open cargo bay door. Newkirk took hold of it and clipped himself onto a smaller cable, which would hold their combined weight as they flew.

Deryn let her gliding wings spread out. As she stepped toward the cargo door, the wind grew stronger and colder. Even through amber goggles the sunlight made her squint. She grasped the harness straps that connected her to Newkirk.

“Ready?” she shouted.

He nodded, and together they stepped off into roaring emptiness. . . .

The freezing airstream yanked Deryn sternward, and the world spun around once, sky and earth gyrating wildly. But then her gliding wings caught the air, stabilized by the dangling Newkirk, like a kite held steady by its string.

The

Leviathan

was beginning its descent. Its shadow grew below them, rippling in a furious black surge across the ground. Newkirk still grasped the grappling hook, his arms wrapped around the cable against the onrush of air.

Deryn flexed her gliding wings. They were the same kind she’d worn a dozen times on Huxley descents, but free-ballooning was nothing compared to being dragged behind an airship at top speed. The wings strained to pull her to starboard, and Newkirk followed, swinging slowly across the blur of terrain below. When Deryn centered her course again, she and Newkirk swung back and forth beneath the airship, like a giant pendulum coming to rest.

The fragile wings were barely strong enough to steer the weight of two middies. The

Leviathan

’s pilots would have to put them dead on target, leaving only the fine adjustments for Deryn.

The airship continued its descent, until she and Newkirk were no more than twenty yards above the ground. He yelped as his boots skimmed the top of a tall pine tree, sending off a burst of needles shiny with ice.

Deryn looked ahead . . . and saw the fighting bear.

She and Alek had spotted a few that morning, their dark shapes winding along the Trans-Siberian Trailway. They’d looked impressive enough from a thousand feet, but from this altitude the beast was truly monstrous.

Its shoulders stood as tall as a house, and its hot breath coiled up into the freezing air like chimney smoke.

A large cargo platform was strapped to its back. A pallet waited there, a flattened loop of metal ready for Newkirk’s grappling hook. Four crewmen in Russian uniforms scampered about the bear, checking the straps and netting that held the secret cargo.

The driver’s long whip flicked into the air and fell, and the bear began to lumber away. It was headed down a long, straight section of the trailway aligned with the

Leviathan

’s course.

The beastie’s gait gradually lengthened into a run. According to Dr. Busk, the bear could match the airship’s speed only for a short time. If Newkirk didn’t get the hook right on the first pass, they’d have to swing around in a slow circle, letting the creature rest. The hours saved by not landing and loading in the normal way would be half lost.

And the czar, it seemed, wanted this cargo at its destination barking fast.

As the airship drew closer to the bear, Deryn felt its thundering tread bruising the air. Puffs of dirt drifted up from the cold, hard-packed ground in its wake. She tried to imagine a squadron of such monsters charging into battle, glittering with fighting spurs and carrying a score of riflemen each. The Germans must have been

mad

to

provoke this war, pitting their machines not only against the airships and kraken of Britain, but also the huge land beasts of Russia and France.

She and Newkirk were over the straightaway now, safe from treetops. The Trans-Siberian Trailway was one of the wonders of the world, even Alek had admitted. Stamped flat by mammothines, it stretched from Moscow to the Sea of Japan and was as wide as a cricket oval—room enough for two bears to pass in opposite directions without annoying each other.

Tricky beasties, ursines. All last night Mr. Rigby had regaled Newkirk with tales of them eating their handlers.

The

Leviathan

soon caught up to the bear, and Newkirk signaled for Deryn to pull him to port. She angled her wings, feeling the tug of airflow surround her body, and she briefly thought of Lilit in her body kite. Deryn wondered how the girl was doing in the new Ottoman Republic. Then shook the thought from her head.

The pallet was drawing near, but the loop Newkirk was preparing to grab rose and fell with the bounding gait of the giant bear. Newkirk began to lower the grappling hook, trying to swing it a little nearer to its target. One of the Russians climbed higher on the cargo pallet, reaching up to help.

Deryn angled her wings a squick, drawing Newkirk still farther to port.

“HOOKING THE PACKAGE.”

He thrust out the grappling hook, and metal struck metal, the rasp and clink of contact sharp in the cold wind—the hook snapped into the loop!

The Russians shouted and began to loosen the straps that held the pallet to the platform. The bear’s driver waved his whip back and forth, the signal for the

Leviathan

’s pilots to ascend.

The airship angled its nose up, and the grappling hook tightened its grip on the loop, the thick cable going taut beside Deryn. Of course, the pallet didn’t lift from the fighting bear’s back—not yet. You couldn’t add two tons to an airship’s weight and expect it to climb right away.

Ballast began to spill from the

Leviathan

’s ports. Pumped straight from the gastric channel, the brackish water hit the air as warm as piss. But in the Siberian wind it froze instantly, a spray of glittering ice halos in the air.

A moment later the ice stung Deryn’s face in a driving hail, pinging against her goggles. She gritted her teeth, but a laugh spilled out of her. They’d hit on the first pass, and soon the cargo would be airborne. And she was flying!

But as her laughter faded, a low growl came rumbling through the air, a sovereign and angry sound that chilled Deryn’s bones worse than any Siberian wind.

The fighting bear was getting twitchy.

And it stood to reason. The frozen clart of a thousand

beasties was raining down onto its head, carrying the scents of message lizards and glowworms, Huxleys and hydrogen sniffers, bats and bees and birds and the great whale itself—a hundred species that the fighting bear had never smelled before.