Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (42 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

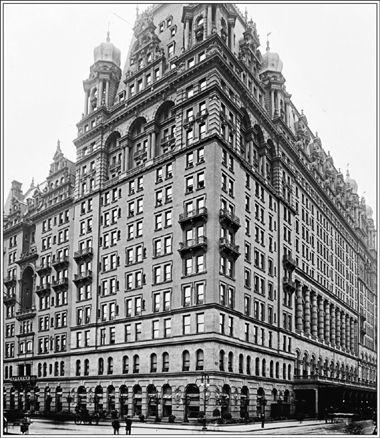

J. Bruce Ismay (at center) was the first witness called to testify at the Senate Inquiry in the East Room of the Waldorf-Astoria.

(photo credit 1.49)

The tabloid villain of the story was followed by its newly minted hero. Captain Arthur Rostron made only a brief appearance in the Waldorf’s ballroom since the

Carpathia

was due to resume its voyage to the Mediterranean that evening. The energetic, blue-eyed Rostron won over the senators with his description of how he had raced to the

Titanic

’s distress position even though, as he acknowledged, it was at some risk to his own ship and its passengers. Senator Smith responded by telling the captain “

Your conduct deserves the highest praise.” Rostron would later receive a Congressional Gold Medal and a “Thanks of Congress” resolution.

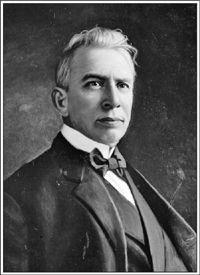

Senator William Alden Smith

(photo credit 1.50)

In the afternoon, it was Second Officer Lightoller’s turn to answer questions, the first of nearly two thousand he would be asked by this committee and the British inquiry that followed. Throughout his testimony, Lightoller acquitted himself well and skillfully steered criticism away from Captain Smith and the White Star Line even while he considered the American inquiry to be “

nothing but a complete farce.” The second officer came to have particular contempt for Senator Smith, whose ignorance of nautical matters led to him being ridiculed by the English press as “Watertight Smith” for asking whether the watertight compartments were meant to shelter passengers. The

London Globe

called Smith “

a gentleman from the wilds of Michigan” who felt it necessary “to be as insolent as possible to Englishmen.” British resentment toward America’s waxing power was captured by the poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who wrote in his diary that if anyone had to drown it was best that it be American millionaires. To the English elites, the U.S. inquiry seemed to be yet another example of American muscle flexing. But a Labor parliamentarian, George Barnes, noted more dispassionately that “

it may be humiliating to some to have an [American] inquiry into the loss of a British ship but … the average person realizes that Americans get to work very quickly, and the average person, I think, is rather glad it is so.”

As the Senate inquiry wrapped up its first day of hearings at the Waldorf-Astoria on Friday, April 19, Arthur Peuchen and his family left the hotel to board an overnight express train for the journey home. At Toronto’s Union Station the next day a large crowd waited to catch a glimpse of the man who had survived the tragedy that, according to the

Toronto Globe

, “

has stirred two continents as they have not been stirred in a century.” Also greeting the Peuchens was a large headline in Saturday’s

Toronto World:

MAJOR PEUCHEN BLAMES CAPTAIN WHO WENT DOWN WITH HIS SHIP

. In the article that followed, the major accused Captain Smith of “criminal carelessness.” At the Peuchen home on Jarvis Street, a telegram awaited requesting that the major give testimony before the Senate inquiry in Washington the following Tuesday. After two days at the Waldorf-Astoria, the hearings were to reconvene on Monday in the U.S. capital. Although utterly fatigued, Peuchen made arrangements to leave the following day. Before his departure, however, he found time to talk to one more reporter, to correct what certain newspapers had attributed to him. “

I have never,” he asserted, “spoken an unkind word about Captain Smith.”

On the following morning, as the major and his wife prepared to leave for Washington, the

Titanic

furnished a ready theme for Sunday’s sermons. At Peuchen’s own church, St. Paul’s on Bloor Street, his friend and neighbor Archdeacon H. J. Cody pronounced, “

The men of our race have not forgotten how to die … sacrifice for a chivalrous ideal is one of the finest features of our history.” This theme was echoed in countless pulpits on both sides of the Atlantic. The Reverend Dr. Leighton Parks, of St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue in New York, could not resist a poke at the women’s suffrage movement by noting that while the men of the

Titanic

sacrificed themselves for women and children, “

those women who go about shrieking for their ‘rights’ want something very different.”

Major Peuchen took the stand before the Senate subcommittee on the afternoon of Tuesday, April 23. His testimony reads as if he were self-assured and even a little self-satisfied, but according to the

New York Times

, he seemed nervous and there were occasional pauses for him to recover his composure. At the end he asked to make a statement in which he repeated his denials of ever having said “

any personal or unkind thing about Captain Smith.” He went on to state,

I am here, sir, more on account of the poor women that came off our boat. They asked me if I would not come and tell this court of inquiry what I had seen, and when you wired me, sir, I came at once, simply to carry out my promise to the poor women on our boat.

At least one of the “poor women” in Boat 6 would have greeted Peuchen’s statement with a derisive snort. Margaret Brown was already miffed that she had not been asked to testify before the Senate inquiry given her prominence on the Survivors’ Committee and the acclaim she was enjoying as a heroine of the

Titanic

. And as a supporter of women’s suffrage, Margaret was not shy about using her newfound fame to wade into the debate over gender equality swirling around the disaster. (One newspaper poet noted how the cry of “

Votes for women” had become “Boats for women/When the brave/Were come to die.”) Margaret Brown stated in an interview that while “ ‘

Women first’ is a principle as deep-rooted in man’s being as the sea … to me it is all wrong. Women demand equal rights on land—why not on sea?”

In fact, the “women and children first” protocol for abandoning ship was not a particularly ancient one. It began with the HMS

Birkenhead

, a British troopship that was wrecked off Cape Town, South Africa, on February 26, 1852. The soldiers famously stood in formation on deck while the women and children boarded the boats, and only 193 of the 643 people on board survived. Hymned as the “Birkenhead drill” in a poem by Rudyard Kipling, it became a familiar touchstone of Britain’s imperial greatness and

AS BRAVE AS THE BIRKENHEAD

was a much-used heading in UK

Titanic

press coverage. A story that Captain Smith had exhorted his men to “Be British!” further burnished the oft-cited claim that Anglo-Saxon men had not forgotten how to die.

It would be up to the blunt-spoken Ella White, one of only two women called to testify at the Senate inquiry (though five others gave affidavits) to throw some cold water on the selfless chivalry of the

Titanic

’s men:

They speak of the bravery of the men. I do not think there was any particular bravery, because none of the men thought it was going down. If they had thought the ship was going down, they would not have frivoled as they did about it. Some of them said, “When you come back you will need a pass,” and, “You can not get on tomorrow morning without a pass.” They never would have said these things if anybody had had any idea that the ship was going to sink.

Chivalrous or not, there was no denying that of the 1,667 men on board, only 338, or 20.27 percent, had survived as compared with a 74.35 percent survival rate for the 425 women. On April 21 the bodies of the

Titanic

’s victims began to be pulled out of the north Atlantic by the

Mackay-Bennett

, a cable ship that had been sent out from Halifax with a hundred tons of ice and 125 coffins on board. The

Mackay-Bennett

’s captain described the scene as resembling “

a flock of sea gulls resting on the water.… All we could see at first would be the top of the life preservers. They were all floating face upwards, apparently standing in the water.” John Jacob Astor’s body was found floating with arms outstretched, his gold pocket watch dangling from its platinum chain. To the ship’s undertaker it looked as if Astor had just glanced at his watch before he took the plunge. It is often written that

Astor’s body was found mangled and soot-covered and that he must therefore have been crushed when the forward funnel came down. Yet according to three eyewitnesses, Astor’s body was in good condition and soot-free, and like most of the other floating victims, he appeared to have died of hypothermia.

On April 25 the body of the Buffalo architect Edward Kent was recovered. In the pocket of his gray overcoat was the silver flask and ivory miniature given to him by Helen Candee on the grand staircase, and these were later returned to her by Kent’s sister. Frank Millet’s body was found on the same day and identified by the initials F. D. M. on his gold watch. The next evening the

Mackay-Bennett

left for Halifax with 190 bodies on board, another 116 having been buried at sea. A second ship, the

Minia

, had arrived on the scene, but after a week’s search it retrieved only seventeen bodies, and two other ships would find only an additional five. The

Mackay-Bennett

landed in Halifax on April 30 to the tolling of church bells and flags flying at half-staff. Horse-drawn hearses took the bodies from the dock to a temporary morgue set up in a curling rink.

Frank Millet’s eldest son, Laurence, had been waiting in Halifax for the

Mackay-Bennett

to arrive and at midnight was allowed to view his father’s body. Early the next morning he accompanied the casket to Boston on a train which also carried the bodies of Isidor Straus and a twenty-one-year-old passenger named Richard White. Heads were bowed at Boston’s North Station as the coffins were wheeled along the platform. Millet’s body was then taken to the chapel at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, where a funeral service was held that afternoon. On viewing the body after the service, Jack Millet wrote to his mother in Broadway that his father’s face was undamaged and had a calm expression. He also noted, “

We are so used to long absences that I can not quite get used to thinking that we shall never see him again.”

Meanwhile, Major Blanton Winship remained in Halifax, sent there by President Taft to examine every corpse in search of Major Butt, though Archie’s body was never recovered.

At Frank Millet’s funeral “Nearer My God to Thee” was not played, though the hymn was ubiquitous at most other

Titanic

memorials. It was sung by a congregation of twenty-five hundred at London’s Westminster Chapel on April 25, during a commemorative service for W. T. Stead that was attended by such notables as future prime ministers David Lloyd George and Ramsay MacDonald. The dowager Queen Alexandra sent a representaive and a message of condolence, and the service ended with the “Hallelujah Chorus.” Psychic messages had already been received from Stead in the afterlife reporting that it was he who had requested that the

Titanic

’s musicians play “Nearer My God to Thee.” The hymn also concluded a packed memorial service for Major Butt held in his hometown of Augusta, Georgia, on May 2. President Taft delivered an emotional tribute to his aide, giving an outline of Archie’s life and praising his loyalty and cheerfulness and noting that “

never did I know how much he was to me until he was gone.” He also spoke of Archie’s devotion to his mother and said, “It always seemed to me that he never married because he loved her so.” At another large memorial service held in Washington three days later by Archie’s Masonic Lodge, Taft broke down during his eulogy and could not continue. The entire assemblage then stood and sang with great emotion “Nearer My God to Thee,” the hymn that Archie had chosen for his funeral because it appealed to his sentimental side.