Generation X (21 page)

"Don't worry. It'll take his highness at least that long to decide b e t w e e n g e l a n d m o u s s e . "

" Y o u p r o m i s e t h e n ? "

"Fifteen minutes and ticking."

Have you ever tried to light thousands of candles? It takes longer

than you think. Using a simple wh ite dinner candle as a punk, with a dish underneath to collect the drippings, I light my babies' wicks—my grids of votives, platoons of

yahrzeits

and occasional rogue sand candles.

I light them all, and I can feel the room heating up. A window has to be opened to allow oxygen and cold winds into the room. I finish.

Soon the three resident Palmer family members assemble at the top

of the stairs. "All set, Andy. We're coming down," calls my Dad, assisted by the percussion of Tyler's feet clomping down the stairs and his back-ground vocals of

"new skis, new skis, new skis, new skis

. . . "

Mom mentions that she smells wax, but her voice trails off quickly.

I can see that they have rounded the corner and can see and feel the buttery yellow pressure of flames dancing outward from the living room d o o r . T h e y r o u n d t h e c o r n e r .

"Oh,

my

—" says Mom, as the three of them enter the room, speech-less, turning in slow circles, seeing the normally dreary living room covered with a molten living cake-icing of white fire, all surfaces de-voured in flame—a dazzling fleeting empire of ideal light. All of us are instantaneously disembodied from the vulgarities of gravity; we enter a realm in which all bodies can perform acrobatics like an astronaut in orbit, cheered on by febrile, lic k i n g s h a d o w s .

"It's like

Paris

. . . " says Dad, referring, I'm sure to Notre Dame c a t h e d r a l a s h e i n h a l e s t h e a i r —h o t a n d s l i g h t l y s i n g e d , t h e w a y a i r must smell, say, after a UFO leaves a circular scorchburn in a wheat field.

I'm looking at the results of my production, too. In my head I'm

reinventing this old space in its burst of chrome yellow. The effect is more than even I'd considered; this light is painlessly and without rancor burning acetylene holes in my forehead and plucking me out from my

body. This light is also making the eyes of my family burn, if only momentarily, with the possibilities of existence in our time.

"Oh, Andy," says my mother, sitting down. "Do you know what this is like? It's like the dream everyone gets sometimes—the one where y ou're in your house and you suddenly discover a new room that you never knew was there. But once you've seen the room you say to yourself,

'Oh, how obvious

—

of course that room is there. It always has been.' '

Tyler and Dad sit down, with the pleasing clumsiness of jackpot

lottery winners. "It's a video, Andy," says Tyler, "a total

video."

But there is a problem.

Later on life reverts to normal. The candles slowly snuff themselves out and normal morning life resumes. Mom goes to fetch a pot of coffee; Dad deactivates the actinium heart of the smoke detectors to preclude a sonic disaster; Tyler loots his stocking and demolishes his gifts. ("New skis! I can die now!")

But I get this feeling—

It is a feeling that our emotions, while wonderful, are transpiring in a vacuum, and I think it boils down to the fact that we're middle class.

You see, when you're middle class, you have to live with the fact

that history will ignore you. You have to live with the fact that history can never champion your causes and that history will never feel sorry for you. It is the price that is paid for day-to-day comfort and silence.

And because of this price, all happinesses are sterile; all sadnesses go unpitied.

And any small moments of intense, flaring beauty such as this

morning's will be utterly forgotten, dissolved by time like a super-8 film left out in the rain, without sound, and quickly replaced by thousands of silently growing trees.

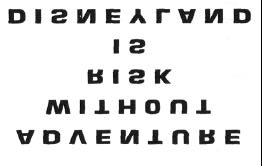

WELCOME

HOME

FROM

VIETNAM,

SON

Time to escape. I want my real life back with all of its funny smells, pockets of loneliness, and long, clear car rides. I want my friends and my dopey job dispensing cocktails to leftovers. I miss heat and dryness and light. 'You're

okay

down there in Palm Springs, aren't you?"

asks Tyler two days later as we roar up the mountain to visit the Vietnam memorial en route to the airport. "Alright, Tyler—

spill.

What have Mom and Dad been saying?" T'Nothing. They just sigh a lot. But they don't sigh over you

nearly

as much as they do about

Dee or Davie." "0h?"

"What do you

do

d o w n

there, anyway? You don't

have a TV. You don't

have any friends—" "!

do,

too,

have friends,

Tyler." "Okay, so you

have friends. But I worry

about you. That's all.

You seem like you're

only skimming the sur-face of life, like a water

spider—like you have some secret that prevents you from entering the mundane everyday world.

And that's fine

—but it scares me. If you, oh, I don't know, disappeared or something, I don't know that I could deal with it." "God, Tyler. I'm not going anywhere. I promise. Chill, okay?

Park over there—" f'You promise to give me a bit of warning? I mean, if you're going to leave or metamorphose or whatever it is you're planning to do—" "Stop being so grisly. Yeah, sure, I promise." "

Just don't leave

me behind.

That's all. I know—it looks as if I enjoy what's going on with my life and everything, but listen, my heart's only half in it.

GREEN DIVISION: To

You give my friends and me a bum rap but I'd give

all

of this up in a know the difference between

flash

if someone had an even remotely plausible alternative."

envy and jealousy.

"Tyler,

stop."

"I just get so

sick

of being jealous of everything, Andy— " There's no stopping the boy. " —And it scares me that I don't see a future. And I don't understand this reflex of mine to be such a smartass about

everything. It

really

scares me. I may not look like I'm paying any attention to anything, Andy, but I am. But I can't allow myself to show it. And I don't know why."

Walking up the hill to the memorial's entrance, I wonder what all

that

was about. I guess I'm going to have to be (as Claire says) "just a teentsy bit more jolly about things." But it's hard.

KNEE-JERK IRONY: The

tendency to make flippant ironic

At Brookings they hauled 800,000 pounds offish across the

comments as a reflexive matter of

course in everyday conversation.

docks and in Klamath Falls there was a fine show of Aberdeen

Angus Cattle. And Oregon was indeed a land of honey, the

DERISION

state licensing 2,000 beekeepers in 1964.

PREEMPTION:

A life -style

tactic; the refusal to go out on

any sort of emotional limb so as to

The Vietnam memorial is called A Garden of Solace. It is a Guggenheim-avoid mockery from peers.

like helix carved and bridged into a mountain slope that resembles

Derision Preemption

is the main

goal of

Knee-Jerk Irony.

mounds of emeralds sprayed with a vegetable mister. Visitors start at the bottom of a coiled pathway that proceeds upward and read from a

FAME-INDUCED APATHY:

series of stone blocks bearing carved text that tells of the escalating The attitude that no activity is

events of the Vietnam War in contrast with daily life back home in worth pursuing unless one can

become very famous pursuing it.

Oregon. Below these juxtaposed narratives are carved the names of

Fame-induced Apathy

mimics

brushcut Oregon boys who died in foreign mud.

laziness, but its roots are much

The site is both a remarkable document and an enchanted space.

deeper.

All year round, one finds sojourners and mourners of all ages and ap-pearance in various stages of psychic disintegration, reconstruction, and reintegration, leaving in their wake small clusters of flowers, letters, and drawings, often in a shaky childlike scrawl and, of course, tears.

Tyler displays a modicum of respect on this visit, that is to say,

he doesn't break out into spontaneous fits of song and dance as he might

were we to be at the Clackamas County Mall. His earlier outburst is over and will never, I am quite confident, ever be alluded to again.

"Andy. I don't

get

it. I mean, this is a cool enough place and all, but why should you be interested in Vietnam. It was over before you'd even reached puberty."

"I'm hardly an expert on the subject, Tyler, but I

do

remember a bit of it. Faint stuff; black-and-white TV stuff. Growing up, Vietnam was a background color in life, like red or blue or gold —it tinted

everything. And then suddenly one day it just disappeared. Imagine that one morning you woke up and suddenly the color green had vanished. I come here to see a color that I can't see anywhere else any more."

"Well / can't remember any of it." "You wouldn't want to. They were ugly times—" I exit Tyler's questioning.

Okay,

yes,

I think to myself, they

were

ugly times. But they were also the only times I'll ever get—genuine capital

H

history times, before

history

was turned into a press release, a marketing strategy, and a cynical campaign tool. And

hey,

it's not as if I got to see much real history, either—I arrived to see a concert in history's arena just as the final set was finishing. But I saw enough, and today, in the bizzare absence of all time cues, I need a connection to a past of some impor-tance, however wan the connection.

I blink, as though exiting a trance. "Hey, Tyler—you all set to take me to the airport? Flight 1313 to Stupidville should be leaving soon."

The flight hub's in Phoenix, and a few hours later, back in the desert I cab home from the airport as Dag is at work and Claire is still in New York.

The sky is a dreamy tropical black velvet. Swooning butterfly palms bend to tell the full moon a filthy farmer's daughter joke. The dry air squeaks of pollen's gossipy promiscuity, and a recently trimmed Pon-derosa lemon tree nearby smells cleaner than anything I've ever smelled before. Astringent. The absence of doggies tells me that Dag's let them out to prowl.

Outside of the little swinging wrought iron gate of the courtyard

that connects all of our bungalows, I leave my luggage and walk inside.

Like a game show host welcoming a new contestant, I say,

"Hello, doors!"

to both Claire's and Dag's front doors. Then I walk over to my own door, behind which I can hear my telephone starting to ring. But this doesn't prevent me from giving my front door a little kiss. I mean wouldn't

you?

Claire's on the phone from New York with a note of confidence in her voice that's never been there before—more italics than usual. After minor holiday pleasantries, I get to the point and ask the Big Question:

"How'd things work out with Tobias?"

'Comme çi, comme ça.

This calls for a cigarette, Lambiekins—hang on—there should be one in this case here.

Bulgari,

get

that.

Mom's new husbnad Armand is just

loaded.

He owns the marketing rights to those two little buttons on push-button telephones—the star and

the box buttons astrid e

the zero. That's like own-ing the marketing rights

to the

moon.

Can you