Fusiliers (41 page)

A general tiraillade began, with the light infantry of both sides using

what cover they could, blazing away at one another. ‘The action became very sharp,’ wrote Lee, ‘and was bravely maintained in both sides.’ Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton was hit in the hand by one shot. Soon it was the turn of the 23rd Fusiliers to be fed into the battle. Seeing larger numbers of redcoats filing up, Colonel Lee felt that discretion was the better part of valour, retiring his men back towards Greene’s position at Guilford Courthouse.

Each side had jockeyed for advantage in that short rencounter with the idea not of extirpating their enemy, but of gaining a feel for whether they were in the presence of one another’s main army or just a far-flung scouting party. Lee rode back to Major General Nathaniel Greene with the news that Cornwallis’s army was marching towards them, and would soon arrive.

A few days before Tarleton and Lee’s affair, Richard Tattersall of the 23rd and John Shaw of the 33rd had ‘made a push for the country’, moving away from their bivouac after a long day’s slog. Were they just looking for food and drink or had they decided to desert? Even they probably weren’t sure. The two and a half weeks since the British left Hillsborough in late February had been spent in a fruitless marching and countermarching about the interior of North Carolina. The excitement of daily exertions as they pressed up to the Dan had been followed by an uncertainty about what would become of them.

Tattersall was one of those scooped up in Lancashire the previous year by the army’s recruiting dragnet. He had joined the Fusiliers with the party of recruits that arrived in December 1780. The strain of months campaigning had evidently got to him. He and his friend Shaw found a farmhouse in the woods and announced themselves, hoping to find food. Lo and behold, the place was already packed with ravenous redcoats. On they went to another farmstead, where a doughty lady presented herself as the wife of Major Bell in the American service, but nevertheless invited them in for something to eat. Sitting beside the warm hearth, eating Johnny Cakes, the two soldiers soon began eyeing the major’s daughters. Why not join our side, asked Mrs Bell, promising them work and the hands of her own daughters. ‘Such good fortune was not to be expected,’ Shaw wrote later, ‘and we had no time to delay, my comrade and I, after we finished our meal, took our leave of the old lady.’ They emerged to find themselves surrounded by dragoons.

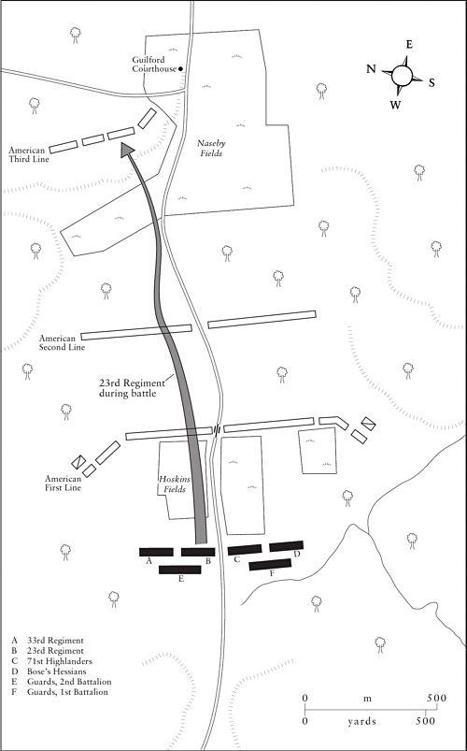

The 23rd’s line of action at Guilford Courthouse

Thinking them a part of Tarleton’s cavalry sent out to find deserters, Tattersall began crying. In fact Mrs Bell had sent word to Colonel Lee’s Legion that she had a couple of redcoats that could easily be made prisoner. By her deception, Mrs Bell thus robbed Earl Cornwallis of two more men, and gained information about what was going on in the British camp for her own side.

Cornwallis did not want to stay too long in one place, because thousands of enemy militia were collecting. Many Tories, on the other hand, had decided to wait and see, Colonel Pyle’s affair having frightened them into inaction. Uncertain of the best course of action, Cornwallis had begun to worry about re-supply. He was considering heading down to the coast, to Wilmington, where a British force sent from Charleston by Lieutenant Colonel Balfour had seized the port in order to open a new line of communications with the earl’s army inland.

Lieutenant General Cornwallis, however, had been receiving reports about General Greene, who was staying close to the British as he received reinforcements. Eight hundred soldiers of the Virginia line under Brigadier General Isaac Huger had joined, followed by nearly 1,500 militia from the same state (many of whom were actually troops seasoned by previous campaigns). While the redcoats marched about, closely observed by Colonel Lee’s corps, he and Greene exchanged messages, as the balance of advantage tipped. ‘One thing is pretty certain,’ Greene told Lee on 9 March, ‘which is Lord Cornwallis don’t wish a general action.’

Colonel Lee interrogated Tattersall and Shaw after they were brought into his camp on 10 March, and having heard what they had to say, decided it was time to egg on his chief, writing back to Major General Greene the following day, ‘It appears to me that his Lordship and army begin to possess disagreeable apprehensions. If you dare, get near him.’ The colonel sent the captured pair of redcoats on to Greene’s headquarters where the general questioned them himself.

The Americans had detected in the British meanderings of early March an aimlessness or lack of clear purpose. Greene gained a further insight into British morale from Tattersall and Shaw. Acute as the American commander was, he could not know all of the possible courses of action that were playing out in his adversary’s mind.

Cornwallis had three choices: first, he might march towards another British force that was operating not far to the north, raiding coastal areas in Virginia; second, he could head south to Wilmington, deposit the sick or wounded he was carting about, re-supply and receive dispatches; third, he could give up the game, accepting his failure to prompt a loyalist rising in North Carolina, returning to South Carolina. Whichever of these options he followed, the British commander would worry about moving with a larger American army to his rear. Greene’s ability, demonstrated in the race to the Dan, to move a little faster than he could had been frustrating when the British were advancing but it could spell disaster if they tried to retreat. Cornwallis, true to character, decided to fight. In any event, he needed to disperse his enemy and buy some weeks or months of freedom to act. He needed another Camden. Cornwallis’s advance guard commander, Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton, would later differ with his chief’s judgement, arguing that ‘a defeat would have been attended with the total destruction of Earl Cornwallis’s infantry, whilst a victory at this juncture could produce no very decisive consequences against the Americans’. Such critics, however, probably understood Greene’s calculations less well than Cornwallis did. If the British could temporarily disperse the Continentals then the caution exhibited so far in the campaign by the American commander would probably have dictated he break off any pursuit.

By mid-March Greene also was ready to give battle. He chose a point a little further up the same road from the skirmish of early on the 15th. It was more open, but undulating, ground, covered for the most part by woods of evergreen pine and some deciduous trees that were just coming into leaf. Greene’s main, or final, position was just in front of Guilford Courthouse, where he posted 1,400 Continental troops (Marylanders and Virginians). The land dropped quite steeply in front of these men to an area cleared of trees known locally as Naseby Fields. The open nature of this place made it a fine killing-ground, so two 6-pounder cannon were also positioned among the Marylanders, overlooking it. Heading towards the British from Naseby Fields, there was a rise, and here, among trees, Greene posted a line of Virginia militia. Hundreds of yards to the front of them, he drew up the North Carolina militia. They were deployed on either side of the road up to Guilford, along a fence where the woods stopped and another area of open ground, Hoskins’ Field, began. This was

another ideal place to engage the redcoats at longer range than in woods, so Greene put another two cannon in the centre of this line. Horsemen were posted on each flank – Lee’s to the right and Colonel Washington’s to the left, and some parties of riflemen assigned to act with them.

The deployment chosen by Greene thus put his 4,400 or so men in three distinct lines, with the British forced to fight their way through the worst troops first, then the Virginia militia in the woods, to the best men posted on the strongest ground. It was an admirable arrangement that married the lie of the land to the distinctive qualities of various contingents.

Most of the Americans were militia called up for limited periods of service. There was nervousness in the American camp about whether the disgraceful stampede of Camden would be repeated, and the North Carolina men once more prove first in flight. Brigadier General Morgan, obliged by sickness to abandon the campaign after his victory at Cowpens, had advised Greene to deploy in lines, and to put steadier militia behind the shakier companies, ‘with orders to shoot down the first man that runs’. Morgan clearly possessed a character even harder than that of Greene. At Guilford, Greene hesitated to give general instructions for one body of Americans to shoot down another, but one of his subordinates, Brigadier General Stevens, whose Virginia militia had also fled at Camden, did take picked men to the rear of his brigade, with orders to kill anyone who tried to flee or raise a panic.

Greene, it is clear, had thought of most things in his plan. He also had the advantage of outnumbering Cornwallis by a considerable margin, since the British army marching towards them mustered no more than 1,900 officers and men. Cornwallis knew the ground, for he had stopped in Guilford during the manoeuvring of the previous weeks, but had no idea exactly how his enemy would deploy. He went into battle, however, undaunted, and after a march of near 16 miles, at mid-day on 15 March.

As the leading redcoats crossed a small creek and saw the open ground of Hoskins’ Field ahead, they began deploying into their battle formation. Colonel Webster moved to the left of the road, keeping the 23rd next to that axis and pushing the 33rd out to his wing. Major General Leslie formed his brigade on the other side of the road to Guilford, with the 2nd Battalion of the 71st nearest to it (and the

23rd), the von Bose Hessian regiment to the 71st’s right. Cornwallis kept certain troops as a second line of his own, ready to plug gaps or rush to a threatened flank; the 2nd Battalion of the Guards was behind Webster, with some jaegers, the Guards Light and Grenadier companies. The 1st Battalion of Guards stood behind Leslie. The army’s small battery of guns was in the first line, on the road, commanded by Lieutenant John MacLeod, and Tarleton’s cavalry in reserve, in the centre but back beyond the Guards.

As at Camden, the British went forward as soon as they were in line. Captain Peter led the 23rd on as acting commanding officer, with the regiment effectively in two wings under captains Saumarez and Champagne. As they went forward, one of them noticed the ‘field lately ploughed, which was wet and muddy from the rains which had recently fallen’. On they trudged towards the fence that marked the end of Hoskins’ cornfield and the beginning of the woods to the fore, observing as they grew closer that the rails were lined with men. MacLeod’s cannon opened fire, sending their ball whooshing into the American lines.

Colonel Webster, on horseback, trotted to the front of his brigade and called out so that all could hear, ‘Charge!’ The men began jogging forward, bayonets fixed and muskets levelled towards the enemy. A crackling fire from their left, Kirkwood’s riflemen, began knocking down a redcoat here or there, but did nothing to check their impetus. When the British line was little more than 50 yards from the North Carolina militia everything seemed to stop for Serjeant Lamb: … it was

… it was perceived the whole of their force had their arms presented, and resting on a rail fence … they were taking aim with the nicest precision. At this awful period a general pause took place; both parties surveyed each other for the moment with the most anxious suspense …

Colonel Webster spurred his horse to the head of the 23rd and bellowed out, ‘Come on my brave Fusiliers!’ Some of the Americans started to run, but most held on for a moment; there was a rippling crash of American musketry when the redcoats were at optimum range, 40 to 50 yards away. Dozens of Webster’s men went down as the musket balls cut legs from under them or smashed into their chests. Lieutenant Calvert worried for an instant how his men might react to such a heavy fire: ‘They instantly returned it and did not give the enemy time to repeat their fire but rushed on them with bayonets.’

Captain Saumarez noted with pride, ‘No troops could behave better than the regiment … they never returned the enemy’s fire but by word of command and marched on with the most undaunted courage.’ Most of the Carolinians did not wait longer but broke and ran. Calvert spotted them disappearing into the trees and felt a pang of frustration that they had got away.

About 400 yards further on, behind a low ridge obscuring what had just happened, the Virginia militia waited with some trepidation. Samuel Houston, a man from Rockbridge County, Virginia, had been standing with others in Steven’s brigade for more than two hours. They had been told to pick a tree and take firing positions, but there were more men than trees, with the nervous Houston observing, ‘The men run to choose their trees, but with difficulty, many crowding to one.’ When Webster’s brigade hit the friends to Houston’s front, the Virginians could hear it all but not see it, adding to their feeling of suspense.

Coming over the ridge that separated the first and second of Greene’s defensive lines, Webster’s brigade had lost some of its order. The 33rd had moved off to the left somewhat, trying to force back Kirkwood’s riflemen. As the 23rd’s officers saw the Virginians in front of them they quickly perceived that some of Stevens’s militia companies had used their waiting time to advantage, piling up brushwood and branches in front of their position. They wheeled the 23rd slightly to the right to get around this obstruction. As Webster’s two regiments came down the gentle slope towards Stevens’s men, a considerable gap had opened between them, leaving the right end of the 33rd’s line and the left of the 23rd’s in the air.