Fusiliers (33 page)

By 29 March Cornwallis’s troops were establishing themselves on the Charleston peninsula itself, having come behind the city to invest it from the north. On 1 April the trenches were opened, the field engineers beginning their approaches and batteries, the vice of earthworks that would be slowly advanced towards the settlement’s landward walls, crushing the defence bit by bit.

The British engineers dug their first trench or parallel several hundred yards from the American works. As the siege progressed, and usually working at night, digging parties pushed their excavations forward, connecting these advances with two more parallels. The third parallel, the one from which the city would be stormed, was only 30 to 40 yards from the American guns. During the long hours of hard labour required to progress with pick and shovel, the defenders pelted Clinton’s men with cannon, grape and musketry. Work in the trenches was dirty and dangerous, all the more so because the usual rules of siege warfare were being violated – the attackers, with thirty guns, had barely one third of the number of the defenders.

Captain Ewald’s jaegers were ordered to work in the siege lines, acting as sharpshooters against the city’s defenders. ‘Our batteries opened,’ he wrote in his journal for 13 April, ‘several pieces of the besieged on the bastion on the left were dismounted.’ Pushing forward their excavations on the 17th Ewald recorded, ‘The besieged fired continuously with grapeshot and musketry, through which five Hessian grenadiers and three Englishmen were killed and 14 wounded.’

By late April the third parallel was being dug and a weary Ewald wrote, ‘The dangers and difficult work are the least of the annoyance:

the intolerable heat, lack of good water and the billions of sandflies and mosquitoes made up the worst nuisance.’ Scores of sick were treated in tents set back from the trenches, for no building suitable for a hospital could be found.

Clinton’s prosecution of the siege was so slow and deliberate as to frustrate many officers, but the defenders did nothing to take advantage of it. In fact day by day they played into his hands. The Continental regiments that had garrisoned the city from the start were reinforced by South Carolina militia, called up from all over the state. The Continental Army also made preparations to send more troops down to help.

Brigadier General Benjamin Lincoln, the American commander, would more wisely have left the city to the militia and kept his picked troops outside it. This, though, proved politically unacceptable to the city’s oligarchs, who insisted Lincoln’s men stay, and sucked as many troops as they could into Clinton’s trap. As the British guns pounded, day after day shattering windows and terrifying civilians, Charleston began to feel the effects of a siege proper – something that had not happened at New York. It became a contest to the finish in which a victorious enemy was expected to sack the town and seize millions in property from those who had resisted.

In addition to wrapping one hand around the neck of South Carolina’s great city, Clinton needed to use the other to fend off any attempt to relieve the siege from the inland side. This duty fell to Earl Cornwallis who arrayed troops in an arc up to fifty miles into the country.

Nisbet Balfour rejoined his regiment on 10 March, after a sea journey that had taken months because of the difficulties of bypassing the French fleet and catching the wind. He returned to find the regiment more than 400 strong, although fifty were already in hospital suffering from the southern agues, and several had been taken prisoner while the 23rd fought its way towards the city. After the trenches had been opened, a strong detachment, 120 men under Major Mecan, had been sent to guard a battery at Fort Johnson, an important point on James Island controlling access to the harbour. With little more than half his regiment left, Balfour bivouacked 40 miles up the Cooper River, sending out patrols to warn of any approaching enemy. This was less dangerous than being in the siege lines, but offered no opportunities for distinction that a fire-eater might seek.

Balfour wrote from his camp in some woods to a friend in New York that he was ‘in perfect health, except the amusement of a few muskettoes [

sic

] and rattlesnakes to look at in the morning’, and predicting that ‘this sun of your latitudes will pepper me’. During his long voyage and duty on the lines Balfour had plenty of time to consider his personal position. He had always operated on the principle that it was essential to be well connected, but his great patron remained in England removed from public life. By returning to America he had placed himself once more under Henry Clinton, a man whom he despised. However, the logic of operations and the balance of personalities in the army began to work in Balfour’s favour.

With each crash of British shot into the walls of Charleston the defenders’ time was reduced, and with each day on outpost duty, Balfour’s personal situation became less isolated. For the 23rd’s commanding officer was gaining the trust of Earl Cornwallis, and that noble general valued new allies because he was losing the faith of his commander-in-chief.

Clinton had been wary of Cornwallis since the campaign of 1776, when he discovered that a remark he made to the earl, disparaging William Howe, was promptly reported back to that general. In April 1780, with his grip closing on Charleston, Clinton jotted in his diary that Cornwallis was spreading rumours, but that when challenged, ‘Lord Cornwallis never writes an answer.’ Several days later the commander-in-chief was worried whether he had done the right thing sending Cornwallis to command the inland forces and fretting about the peer’s aide-de-camp Charles Ross: ‘He [Cornwallis] will play me false, I fear; at least Ross will.’ Even so, these suspicions or rivalries were kept in check as long as the army was successful and on 11 May, after four months’ campaigning, its operations were crowned with triumph.

By the night of 11 May, Captain Ewald’s jaegers were fighting from a storming trench just thirty paces from the enemy defences, enduring a ‘horrible’ fire that cut many men down and dismounted all of the forward British guns (although the Americans did not realise their success). Clinton forced matters by firing red-hot shot into the city, a grim tactic that, if kept up, would burn down the entire place. ‘During this murdering and burning, I heard the sound of a drum,’ wrote the Hessian jaeger. An American drummer had been sent up to the walls and was beating out the signal for a parley. Brigadier Lincoln had

previously refused to surrender, but with the British ready to storm or incinerate the town, further resistance was futile.

When the defenders marched out, the British realised the scale of defeat they had inflicted. In his dispatch to London, Clinton said he had taken 5,618 enemy troops as well as 1,000 armed sailors. The loss to the attacking forces was 76 killed and 189 wounded. The British were quite unprepared to deal with such a vast number of captives, and in any case it was the 2,600 Continental troops that formed the mainstay of the garrison – most of the remainder had played little active role in the defence, and were soon released on their word, or parole, that they would never bear arms against the King’s troops again.

In addition to the loss of these regiments and 400 cannon, the Americans had to surrender a squadron of frigates. The city merchants were further mortified by dozens of trading ships being impounded. There was a vast sum in prize money to be made from the Charleston business, and a tetchy dispute soon started between army and fleet over whether the sailors were entitled to half of the money. Clinton had made himself a fortune.

The fall of Charleston was in many respects worse for the Americans than Saratoga had been for the British. In addition to losing a large army, a city central to the prosperity and livelihoods of the southern states had been seized. Patriot spirits were depressed, and the war party in London received an enormous boost. That ardent Whig, Richard Fitzpatrick of the Guards, wrote to his friend Charles Fox, ‘The camps fired a

feu de joie

upon this occasion, because now as you may imagine

the war is finished

.’ The prediction proved erroneous, but many of those who had assumed since Burgoyne’s surrender that George III’s Ministry was simply looking for the right peace terms were disabused. After Charleston it became clear that the British army was fighting again, not for time but to win.

General Clinton quickly began re-embarking his

corps d’élite

, the light infantry and grenadiers, for a voyage back to New York. He intended to leave behind Lord Cornwallis and a small army that included the 23rd Fusiliers. Civil rule would be re-established in South Carolina as it had been in Georgia. Thousands of loyal inhabitants would be armed and formed into militia regiments so that Cornwallis’s regulars might move to North Carolina and repeat the process, working their way up the states. Cornwallis was given his orders, and General Clinton even had a task in mind for Lieutenant Colonel Balfour.

As they considered how South Carolina should be garrisoned, British commanders were conditioned by geography. Charleston’s immediate hinterland, stretching about 100 miles inland, was a swampy, unhealthy terrain crossed by several major rivers. This lowland was also the most economically productive part of the province, with its large plantations. Beyond the coastal strip, there was a distinct change, a rolling landscape of sand hills, the so-called piedmont, began; and beyond that, a further 100 miles or so from the sea, were the Appalachian mountains. The uplands had been colonised later than the coast, by settlers coming down from the north on the Great Wagon Road from Virginia. As for the mountains, they were home only to a few frontier communities.

Cornwallis soon realised that the piedmont would have to be dominated. There were three reasons for this: Continental Army troops marching down via Virginia and North Carolina along the Great Wagon Road would arrive in those sandy uplands, not on the coast; the main rivers were more easily forded there, so therefore less of a barrier to military operations; and there were some sizeable communities of loyalists among the new inland settlements that would have to be protected. So whereas some of the British generals who had fought in the north four years earlier thought that operations in America any further than 15 miles from their fleet were a dubious proposition, Cornwallis and his people would have to operate ten times that distance from their main base and stores at Charleston.

Although the war had been going on for five years, the army’s push deep into South Carolina was its first concerted attempt to establish control over a large inland territory. The few months of fighting in the Jerseys during the first half of 1777 were the only similar experience that Cornwallis, Balfour or Mecan had. Even so, the bases at New York or Rhode Island had been maintained for years with minimal garrisoning of the hinterland. In Georgia, captured the previous year, royal forces were thinly deployed away from the coast.

The task General Clinton had in mind for Balfour was to establish the new order in a far-flung part of the backcountry. On 22 May, he invited the lieutenant colonel to discuss this perilous mission. Clinton was a miserable physical specimen compared to Howe, Balfour’s handsome strapping hero of old. The man giving Balfour his orders was short, his few strands of grey hair were scraped across a bulbous pate, his lower set of teeth protruded beyond the upper and he tended

to mumble. Clinton, though, was cleverer and far more intellectually engaged than his predecessor, and as he spoke to the commanding officer of the 23rd the general detected the old prejudices of the 1777 campaign.

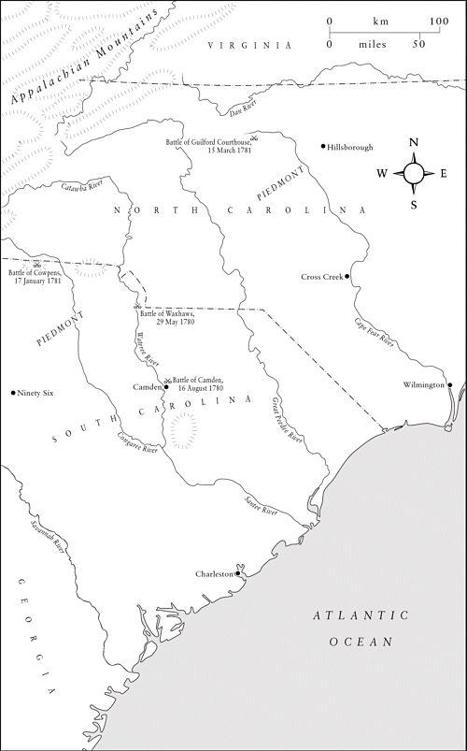

Principal sites of the southern campaigns

Major Patrick Ferguson was to be sent under Balfour’s command as inspector of militia. It was to be Ferguson’s task to raise several new regiments of Tories in the backcountry. Ferguson, an aggressive and innovative soldier, had fallen foul of Howe during the Philadelphia campaign, when the general had disbanded Ferguson’s special corps of sharpshooters equipped with rifles of his own design. Ferguson, though, had retained Clinton’s faith, so both Balfour and Cornwallis immediately suspected that Ferguson was being sent upcountry as Clinton’s representative.

Balfour wondered aloud to his commander-in-chief whether Ferguson was the right man for the job – it was generally reported that the new inspector of militia was violent-tempered and ill-treated his men. ‘I am not interested in “general” reports,’ replied Clinton, brushing Balfour aside, but noted to himself, ‘I see [the] infernal party still prevails.’ The general knew that Balfour was his enemy and yearned for an opportunity to trip him up, writing in his journal, ‘I wish this remark of

Balfour’s

turns out lucky.’ Perhaps Clinton even entertained the hope that Balfour might not return from his grim backcountry mission.

Several days later, Balfour set off with a small brigade of 580 under his command, including some light infantry and loyalists of the American Volunteers and the Prince of Wales’s Volunteers. A detachment of the 23rd Fusiliers would also travel inland with their commanding officer but most of the regiment would initially remain in Charleston.