Fobbit (37 page)

Authors: David Abrams

Sure, Abe Shrinkle thought of his fellow Americans—the ones out there on patrol every day, encased in Kevlar, the weight of the flak vests pulling down on their shoulders like a yoke; the ones out there cocking back their leg and kicking down the doors of suspected bomb makers only to find a mother and her three children huddled in the corner, even the drapery of her black abaya

fluttery with fear; the ones riding dusty mile after dusty mile down the Sadr City streets, scanning the rooftops, the doorways, the heart-stopping piles of trash; the ones who came back to Triumph each night, shucking their vests and helmets and collapsing on their cots, too tired to even lift a thumb for a quick round of Xbox. Yes, Abe still let them parade through his conscience but he could do nothing more than let them trudge along on their funereal march, bass drum beating a somber tempo and the trumpets and tuba bleating in a minor key. He could do nothing more than that, could he? He’d been fired—sacked, as Richard Belmouth would say—and he was no longer part of this war. Duret had removed him from the action, snatched him out of harm’s way, and, though his men—his

former

men—still chewed at Abe’s guilty conscience, he had to admit he was grateful. If for nothing else than to be given the opportunity to come over here to the land of nipples and Foster’s. He would forever be in Vic Duret’s debt for this small, incidental favor. He was an officer stripped of rank and responsibility and weapons. He could no longer order one man to kill another, nor could he legally do the killing himself. He was through with the war and he just needed to bide his time for another—what was it? Three months? No, two and a

half

. The beer was making his brain heavy and slow to process. Another two and a half months and he’d be home free, back to soil where, he’d already decided, he would resign his commission, shed his uniform, and grow a goatee. Yes, a goatee would be nice. Maybe just a soul patch if the hair didn’t come in as thick and full as he hoped. Something professorial, something hip and with-it, something completely unrelated to what he’d been through over here, something far removed from the person who had once flame-broiled an innocent man to death.

Abe leaned back in the inner tube, spread his arms and legs, and let the wintergreen pool water lick his fingers and toes. He was alive, goddamnit, he was alive and he would stay that way for the next two and a half months, even if that meant coming to float in this protective womb of a pool every day, then that’s what he would do. Jolly good.

He stared at the sky and marveled at how empty, how blank it was at that moment. Not a cloud, not a helicopter whisking someone to a combat support hospital, not even a stray bird.

He brought the Foster’s to his lips and heard someone in the poolside crowd whistling at him, making the cartoon sound of a falling bomb, and he saluted with the beer can and called out, “Cheers, mate!”

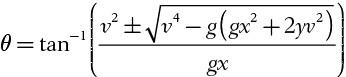

The mortar had a mind of its own. It knew what it wanted. Flesh, human flesh. And if it couldn’t have that, if it had to settle for the cobblestone of the street or the moist cushion of a farmer’s field, then it would concentrate all its effort into sending fragments into as wide a circumference as possible, the hot shards of shrapnel finding their own incidental stoppages of human flesh, chewing their way through epidermis, muscle, vein, viscera, and organ. The mortar still preferred a direct hit, and if it could start at the crown of a skull and bore down through brain, spine, heart, bowel, and leg, and finish with heel, then it could die knowing it had just eaten the perfect Last Supper. This is what the mortar lived for and, come to think of it, died for. This is why it concentrated so much thought and effort into the parabolas of trajectory and so carefully calculated rate, speed, wind resistance, and curvature of the earth: all for the direct hit. Taking into consideration launch velocity, inclination angle, horizontal distance, and maximum altitude, to hit a target at range

x

and altitude

y

when fired from (0,0) and with initial velocity

v

the required angle(s) of launch q are:

Precise calculation of variables is necessary when attempting direct hits.

The men who launched the mortar couldn’t have cared less about parabolas or direct hits, it didn’t matter one way or another to them if the mortar struck cobblestone or skull, as long as the end result brought maximum death and damage and bought them another day’s headline. The men with their goat-meat breath and tongue-tangling supplications to Allah cared only about quickly setting up the tripod and firing tube from the back of a Toyota pickup truck in some quiet out-of-the-way neighborhood and launching with hasty aim. They cared only about firing blindly, then making a clean getaway, and if the end result was severed limbs in the marketplace, all the better, praise Allah. If they missed—and the mortar landed in a canal or a remote cow pasture—then, oh, well, there was always another day.

But the mortar cared. It cared where it hit, who it struck, how it spent its final moments of life before the death that brought wholesale death to others. It cared about the final target, whether it was rock, soil, water, or flesh. This is all the mortar thought about on the upward flight, the peak of the arc, and the down tilt of final descent. Sometimes, the very thought of opening its maw and gobbling a bellyful of human flesh filled it with such anticipation that it started to whistle a happy tune in its final moments, keening a kind of joy unknown to man.

No one saw it coming, they would all testify later. They

heard

it, yes, but never saw it. They only witnessed the aftermath: the red jetted spurt erupting from the center of the water—the dead center, you might say—as if the mortar had struck from below, pushing up from the bottom of the pool instead of falling from the sky. By the time the whistle registered on their brains and they realized what that awful sound portended—

oh, bloody fuck!

—there was no time to react, nothing to shout, only enough time to throw an arm across their eyes, as if

that

would protect them. And when they finally lowered their arms, all of them in their bikinis and trunks and Speedos-with-a-bulge still standing intact and realizing how lucky they were the mortar had struck dead center in the pool which, thanks to all those gallons of water, had cushioned them from the impact, they could only stare with slow-gathering shock and sadness at the watery smoky hole that had once been their pool. At that point, they were only thinking of how rotten their afternoons would be now that they no longer had a pool. What now? Sit in their trailers and slow roast to death with warm Foster’s?

It was only when Glennice, reclining in tan-collecting bliss only moments before, sat up and started screaming that they looked over and saw the arm in her lap, the fingers still gripping the can of beer. It was only then that it hit them with a punch of nausea: that poor bloke Belmouth was gone. He’d taken a direct hit from the mortar while the rest of them had survived—drenched with the pink rain from the pool, yes, and suffering the unforgivable horror of a severed arm in one’s lap—but alive nonetheless.

Alive!

And just as quickly, with just as much certainty, Belmouth was gone, evaporated in the afternoon heat. It was almost too much for their minds to take in. Blink, he’s here, blink, he’s gone. Only a smoking, half-empty pool and an arm in a lap remained as evidence that their newest friend—

such a likable chap

—had ever walked the earth.

Someone suggested calling the British embassy but none of them moved. In the blistering Baghdad heat, they were all frozen as they stared at Glennice’s lap.

Poor bloody bloke.

28

LUMLEY

L

ieutenant Fledger, clad in full battle armor as if he’d already been prepared for the onslaught of grief his men were about to feel, burst through the door of the shower trailer and announced, “Men! He’s dead!”

And so that’s how they heard—three short, barked words. In the hiss and humidity of the water, Lumley and his men looked at Lieutenant Fledger, barely comprehending what he’d said. All they knew was that the company commander stood in their midst and they were naked.

The narrow trailer had been reconfigured with two rows of ten shower stalls and a long wooden bench running down the length of the trailer in the middle. The stalls had no curtains, so one was forced to keep his back turned to the room if one was modest; if not, if one was unabashedly proud of his manhood’s length and girth, then the soap down was done in full view for all to see. Those in the opposite stalls and those waiting their turn on the bench had nowhere else to put their eyes—especially those on the bench who were, unfortunately, dick-level to their comrades.

Because there were no shower curtains, water streamed freely out onto the floor, where it swirled in a grayish mix of shampoos, soaps, and body washes—not to mention the clots of pubic hair, urine (courtesy of those who thought of the shower stall as a free standing toilet), and snot-oysters (courtesy of those who thought of the shower stall as their personal Kleenex). The wicked-looking lake of shower water and detritus forced those soldiers waiting their turn to keep their change of clothes stacked in precarious piles along the bench. At any given time, upon entering the shower trailer, you’d see half a dozen half-naked soldiers perched on the bench, feet tucked under them like birds, anxiously keeping a mound of clothes in check, constantly patting and restacking the trousers and T-shirts. Waiting for the next stall to open up was always a tense game of balance and shepherding clothes. Pity the soldier whose fresh-laundered underwear took a tumble off the bench into the foul water below. They all wore flip-flops (dubbed “shower shoes” by the military) and no one but

no one

went barefoot in here—they sure as shit weren’t going to put their feet down in

that,

oh,

hell

no!

Long-handled squeegees were supplied in each shower trailer and a soldier, upon finishing his shower, was expected to do his part by pushing the water to the drain in the center of the trailer. The drain grates clogged easily and remained that way until the Twee maintenance crew from Thailand came at lunchtime to hand scoop the American filth into a plastic bag. And so sweeping with the squeegee had little effect on the water other than to create a system of ripples and waves that sloshed from one end of the trailer to the other.

When Lieutenant Fledger walked through the door and announced the bad news to those seventeen naked men of his, Specialist Zeildorf was in the midst of pushing a tide of water toward the drain. Gray soup splashed over Fledger’s boots and left a few dark curlies as it receded. Hardly the reception he, an officer in the United States Army, had been expecting. He lifted first one foot, then the other. This was like something out of a cartoon, but he—a reasonable officer in the United States Army—would choose to ignore it . . . for the time being. There were other pressing matters at hand. As a company commander of two months, he was untested in the task of delivering death notices to his men. Since Captain Shrinkle’s departure, Bravo Company had gone through a charmed period of zero KIAs.

Before coming to the shower trailer, Fledger had looked through his West Point textbooks and his class notes but there was nothing to properly prepare him for such heartrending moments as this. He was a Polar explorer, all alone on this ice cap of grief.

He cleared his throat and tried again. “Men! Listen up! I’ve got some bad news and I think you need to sit down for what I’m about to tell you.”

“I think we’ll stand, if it’s all the same to you, sir,” said Brock Lumley from over his shoulder. He’d already had his back turned and his hands cupped over his crotch before Fledger finished speaking.

“What’s going on?” Jacovich shouted over the static of his shower. “Who is that out there? I can’t see a fucking thing!” Jacovich, shampoo in his eyes, blindly groped for a towel.

“It’s okay, men. I know you’re upset. But trust me, time will heal all your wounds.”

“What the fuck’s he saying?” Harris whispered to Snelling, but none too softly.

“Beats me,” said Snelling from his crouch on the bench, wishing Harris would step back into his shower stall and take his hairy dick with him.

As the highest-ranking enlisted soldier in the shower trailer, Lumley spoke for the group. “Sir, I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but as you can see, we’re a little preoccupied right now. Is there something you needed?”