Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (24 page)

Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

Heat a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add the oil, then the garlic and sizzle for a few seconds, before adding the preserved vegetable. Stir-fry briefly together until they smell delicious (take care not to burn the garlic). Add the beans and stir-fry until everything is hot and fragrant, seasoning with salt to taste. Serve.

VARIATIONS

Fava beans with spring onion

Boil, refresh and drain the beans as in the recipe above. Then stir-fry them with four or five spring onions, finely sliced, a pinch of sugar and salt to taste. It’s best to add the spring onion whites at the beginning and the greens just before the wok comes off the heat.

Fava beans with spring onion, Sichuan-style

Use the method for fava beans with spring onion just above, but omit the sugar and sprinkle the finished dish with a little ground roasted Sichuan pepper or Sichuan pepper oil.

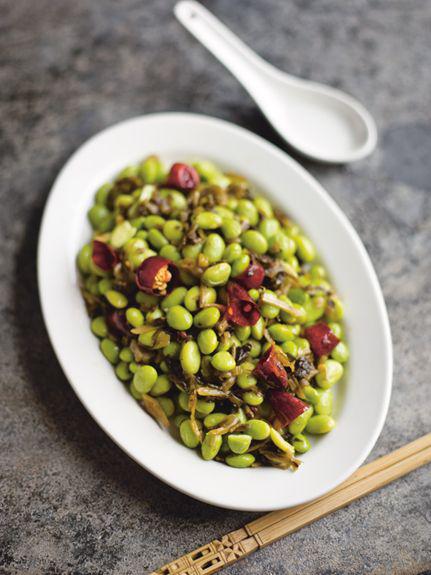

STIR-FRIED GREEN SOY BEANS WITH SNOW VEGETABLE

XUE CAI MAO DOU

雪菜毛豆

Young green soy beans, commonly known as edamame, are one of my favorite vegetables, small and exquisite, their color a sweet pea green that brightens up any supper table. You may serve them boiled, in their fuzzy pods, for the pleasure of popping them out and nibbling them with a glass of beer. Otherwise, they can be steamed or stir-fried, or used in colorful “eight treasure” stuffings. I’ve even had them, dried but still bright green, in mugs of salty green tea in rural Zhejiang Province!

The following dish is one that I enjoyed on a September noon in the Zhejiang hills, when my friend A Dai took me to visit an organic chicken farm. We explored the farm, where healthy-looking chickens pecked around a slope stocked with bamboo, persimmon, camphor and loquat trees, then walked down to the farmhouse for lunch. This recipe, made with “snow vegetable,” one of the favorite local preserves, was on the table that day and I’ve never forgotten it. You can add more or less snow vegetable as you please and you might like to pep it up with a little chilli and Sichuan pepper, to give it a Sichuanese twist. Either version is great served either hot or cold. The same method can be used to cook peas or fava beans.

Salt

9 oz (250g) fresh or defrosted frozen green soy beans (shelled weight)

2 tbsp cooking oil

5 dried chillies (optional)

½ tsp whole Sichuan pepper (optional)

2 oz (50g) snow vegetable, finely chopped

½ tsp sesame oil

If using fresh soy beans, bring a panful of water to a boil, add salt, then the beans. Return to a boil, then cook for about five minutes, until tender. Drain well. (Frozen soy beans are already cooked.)

Heat a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add the oil and swirl it around. If using the spices, add them now and sizzle them very briefly until you can smell their fragrances and the chillies are darkening but not burned. Then add the snow vegetable and stir-fry briefly until fragrant.

Add the beans and stir-fry briefly until everything is hot and delicious, seasoning with salt to taste. Remove from the heat, stir in the sesame oil and serve.

VARIATION

Stir-fried green soy beans

Take 9 oz (250g) fresh or defrosted frozen green soy beans (shelled weight). If they are fresh, boil them as described in the main recipe, then drain. Cut a strip of red bell pepper into small squares about the size of the soy beans. Add 2 tbsp oil to a wok over a high flame. Add the beans and pepper squares and stir-fry until hot, seasoning with salt to taste. Remove from the heat, stir in 1 tsp sesame oil and serve.

STIR-FRIED BEANSPROUTS WITH CHINESE CHIVES

JIU CAI YIN YA

韭菜銀芽

In China, mung beans and soy beans are both commonly sprouted. The thicker, coarser soy bean sprouts tend to be used in soups, while mung bean sprouts, which are those you find in Western supermarkets, are usually stir-fried, as here. They are known in Chinese, rather poetically, as “silver sprouts.”

4¼ oz (125g) Chinese chives

4 oz (100g) beansprouts

2 tbsp cooking oil

A few fine slivers of red bellpepper, for color (optional)

Salt

1 tsp Chinkiang vinegar

Trim the chives, discarding any wilted leaves, and cut them into sections to match the beansprouts. Keep the white ends and the green leaves separate.

Bring a panful of water to a boil. Add the beansprouts and blanch them for about 30 seconds to “break their rawness.” Drain well.

Heat a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add the oil and swirl it around. Add the chive whites with the red pepper, if using, and stir-fry briefly until fragrant. Add the chive leaves and stir a few more times. Add the beansprouts and stir-fry until everything is hot and fragrant, seasoning with salt to taste. Stir in the vinegar and serve.

VARIATION

Beansprouts with chilli and Sichuan pepper

Blanch the beansprouts as in the recipe above. Then heat oil in a wok, add some halved, deseeded Sichuanese dried chillies and Sichuan pepper and stir-fry until fragrant before adding the beansprouts. Season with salt to taste.

Leafy greens are one of the great unsung joys of Chinese eating. Often mentioned only as an afterthought on restaurant menus (usually as “seasonal vegetable”), they are a vital and essential part of the Chinese diet and no supper table is complete without them. There are varieties for almost every season and every region, from the commonest spinach, bok choy and Chinese leaf cabbage, to more exotic specialities such as garland chrysanthemum, wolfberry and purslane leaves. Many of these vegetables are very local, such as the exquisite green and purple rape shoots of Hunan, as subtly pleasing as asparagus, or the tender young alfalfa sprouts and Indian aster leaves adored by the Shanghainese. Often, such greens will simply be stir-fried with a little salt and perhaps ginger or garlic, but they may also be blanched and served cold as a salad, or boiled, braised or steamed.

And when it comes to Chinese-style greens, you can forget the idea that you will eat them only out of duty. Many Chinese recipes for such vegetables are so delicious that for me they are often the highlight of the meal. Chinese or any other kind of cabbage cooked with a handful of dried shrimp is so tasty that it’s almost a meal in itself, with a little steamed rice. Something amazing seems to happen in the wok when you cook spinach with ginger and garlic: an everyday vegetable transformed into an irresistible delicacy. Just taste it. And cooking doesn’t get much easier than Blanched Choy Sum with Sizzling Oil, but I defy anyone to find a tastier way of serving this everyday vegetable. (The same method works well for a host of other greens, including non-Chinese varieties.)

Many of these recipes use vegetables that are easily available in markets and supermarkets in the West; others can be found in the fresh produce sections of typical Chinese supermarkets. You’ll also find mention of some more unusual varieties that can only occasionally be found in Chinese shops, but are well worth hunting down. And I’ve also included a few cooking suggestions for vegetable varieties that are rarely found in China, but lend themselves well to Chinese ways of cooking, such as Brussels sprouts and purple-sprouting broccoli. I hope you’ll come to regard many of these recipes as basic cooking strategies that can be applied to whatever you find in your kitchen, or have growing in your garden or allotment.

In the long run, I do hope that a wider variety of Chinese leafy greens will become available to people living in the West and will be cultivated locally. Many are easy to grow and particularly nutritious. Supermarkets already stock bok choy and choy sum: why not young rape shoots, purple amaranth and Chinese broccoli?

Tips for stir-frying leafy greens

The wok-seared juiciness of leafy greens stir-fried in the volcanic heat of a professional wok stove is impossible to achieve on a domestic burner, but there are a few ways to make the most of stir-frying your greens at home.

– Most importantly, do not overload your wok: in general, I advise stir-frying no more than 11–12 oz (300–350g) raw greens in one go. Any more than this and you’ll find it hard to achieve sufficient heat.

– Before stir-frying raw greens, dry them as far as possible. (You can use a lettuce spinner.)

– Blanch bulky greens or those with thick stems before stir-frying to “break their rawness.” This will shrink them to a manageable volume and ensure that thick-stemmed greens are tender. You don’t need a lot of water, just enough to immerse the vegetables.

– Always stir-fry in a preheated wok, over the hottest possible flame.

– Season with salt towards the end of the cooking time and stir swiftly to incorporate; if you add salt too early, it will draw water out of the vegetables and they will be less juicy and wok-fragrant.

BLANCHED CHOY SUM WITH SIZZLING OIL

YOU LIN CAI XIN

油淋菜心

This dish of bright, fresh greens in a radiantly delicious dressing uses a common Cantonese flavoring method in which cooked ingredients are scattered with slivered ginger and spring onions, followed by a libation of hot, sizzling oil and a sousing of soy sauce. The hot oil awakens the fragrances of the ginger and onion slivers and the soy sauce gives the vegetables an umami richness. It’s one of the quickest and easiest dishes in this book and I can never quite believe how wonderful it tastes.

The same method can be used with many kinds of vegetables, including spinach, lettuce, bok choy, broccoli, Chinese broccoli and purple-sprouting broccoli. Just adjust the blanching time according to your ingredients: you want them to be tender, but still fresh-tasting and a little crisp. At the Wei Zhuang restaurant in Hangzhou, I once had a beautiful starter in which four ingredients—water chestnuts, romaine-type lettuce hearts, peeled strips of cucumber and bundles of beansprouts—had been separately blanched, then bathed like this in hot oil and soy sauce.

11 oz (300g) choy sum

2 spring onions

½ oz (10g) piece of ginger

A small strip of red chilli or red bell pepper for color (optional)

1 tsp salt

4 tbsp cooking oil

2 tbsp light soy sauce diluted with 2 tbsp hot water from the kettle

Bring a panful of water to a boil.

Wash and trim the choy sum. Trim the spring onions and cut them lengthways into very fine slivers. Peel the ginger and cut it, too, into very fine slivers. Cut a few very fine slivers of the chilli or bell pepper, if using.

Add the salt and 1 tbsp of the oil to the water, add the choy sum and blanch for a minute or so until it has just lost its rawness (the stems should still be a little crisp). Drain and shake dry in a colander.

Pile the choy sum neatly on a serving dish and pile the spring onion, ginger and chilli or pepper slivers on top.

Heat the remaining oil over a high flame. When the oil is hot, ladle it carefully over the spring onions, ginger and chilli. It should sizzle dramatically. (To make sure the oil is hot enough, try ladling a few drops on first, to check for the sizzle. As soon as you get a vigorous sizzle, pour over the rest of the oil.)

Pour the diluted soy sauce mixture over the greens and serve.

VARIATION

Purple-sprouting broccoli with sizzling oil

Purple-sprouting broccoli is not a Chinese vegetable, but it tastes spectacular when given the sizzling oil treatment. Blanch 11 oz (300g) broccoli as above, but add a few slices of peeled ginger and a couple of pinches of sugar to the salt and oil in the blanching water. Lay the drained broccoli on a plate and finish with 3 tbsp sizzling-hot oil and 2 tbsp diluted soy sauce, as in the main recipe.