Read Europe in the Looking Glass Online

Authors: Robert Byron Jan Morris

Europe in the Looking Glass (11 page)

IT WAS SCHILLER

, more than a hundred years ago, who first instilled into the younger generation of his countrymen that artificial restlessness which can only find expression in forsaking all and setting out upon a walking-tour. Under the disruptive influences of the immediate post-war years, with the fluctuations of the mark, the uncertainty of employment, the threat of starvation, and the consequent break-up of many homes, the vagrant impulse of every young German has been accentuated. Throughout the whole of northern Europe, with the exception of France, in all the countries that once comprised the Austrian Empire, in Switzerland, and above all in Italy, these couples of bare-kneed, khaki-clad figures, dirty, smelly, golden-haired and, perhaps, but probably not, redeeming their sordid exterior by the joint possession of a guitar, are to be seen on all the large main roads, plodding through the dust of summer and the mud of winter. It is said to be a wonderful spirit that actuates them, the love of the earth, of nature, of mankind. In these days, the glorification of YOUTH in capital letters has displaced that universal admiration for MANHOOD which characterized our parents. And so these temporary negations of civilization are condoned, encouraged and admired. It is

‘Wanderlust’

, say the young men; instead of becoming clerks, they set off into the unknown, chained to Freedom, carefully careless. With their spare money they purchase Baedekers and atlases.

A little time ago Cambridge scented a new era in this aged, but momentarily exaggerated, doctrine. A magazine bearing the word ‘Youth’ imprinted on a burnt orange cover, began a watery and vaguely improper existence. In the Youth

movements of modern Germany, asserted this particular facet of Cambridge opinion, lay the only hope for modern Europe. To us, therefore, at a loss for occupation in the cat-, cow- and chicken-ridden interstices of the

Iperoke

, the two Messiahs out of Albania presented an opportunity to examine more closely this phenomenon that we had hitherto observed only at a distance or in print. We invited them to a bottle of red wine.

Their names were Herbert Fleischmann and Ludwig Schwert. Fleischmann was five feet eleven inches in height, with matted fair hair, a pleasant, broad, smiling mouth, and a long plebeian nose with a bulbous end. Schwert was short, but well proportioned, with dark hair and skin. His eyes twinkled and his mouth was elfin with a firm though protruding upper lip. He was Bavarian, Fleischmann Silesian. Both were clothed in a prevailing tone of khaki, varied with occasional knitted garments colourless with age and wear. Fleischmann sported a pair of laced field-boots. Schwert’s legs were encased in Bavarian stockings cut short at the instep to display the tops of two brilliantly-patterned, knitted socks.

For four years they had been at the University of Heidelberg together. At a glance the age of each would have appeared to have been about twenty-two. Fleischmann, however, had served in the war for two years. Then at the end of his time as a student, he had spent eighty-four thousand marks on a woman in Breslau. ‘Four thousand pounds,’ translated David; while I computed it at four and six. In any case disaster had followed. On top of this extravagance the whole of Fleischmann’s family, father, mother, and sister had followed one another to a succession of early graves. Schwert, the faithful Jonathan of old days, had come forward, and they had set off on their

Weltreise

. In England they would have gone out to the colonies. As Germans, the call to Perpetual Youth had transformed them into parasites.

Schwert provided the brains and resource of the party. This was evident from the overwhelming volume of Fleischmann’s conversation. His sentences were pitched in a monotonous but authoritative key, like those of a guide to St Paul’s. He was,

in fact, a guide to his own achievements. His remarks were punctuated with metallic imperatives. ‘

Hören Sie

!’ and ‘

Wissen Sie

?’ and he had a habit of emphasizing his facts by wagging a forefinger in front of the bulb of his nose. Whenever he began to speak he gave a heave and threw back his shoulders.

They had already been away three years and they rattled off a sing-song account of their itinerary. First they had made their way to Odessa, and gone thence in a diagonal line across the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to Helsingfors. Then, though ostensibly on their way round the world, they had come south. They were absolutely without funds. Schwert, in fact, had lately been obliged to have some gold stopping removed from his teeth, with which to raise money. David said that this was heroic. On the ship they had had nothing to eat all day, until the Albanian shepherd with pleasant smiles had given them some of his melon. Their plan, they said, was to land at Patras, and there find enough work to take them to Athens. David then offered to take them there instead.

This constituted a bond of gratitude. Like chorus girls on the ramp, they produced from their breast pockets photographs of themselves arrayed in their elaborately

Wandervögel

garb, and posed in manly attitudes before a studio backcloth of classical urns and foliage. These photographs form an important part of the equipment of every professional young German beggar. He can occasionally sell them, or accept charity under the pretence of doing so, thus avoiding obligation. Beneath the pictures in question was announced in almost all European languages the fact that they were going round the world. Fleischmann even boasted an armlet embroidered to the same effect.

It was indeed their real intention to beg, borrow or steal their way over all the five continents. They hoped to be home in 1936. Thus can Youth and Wanderlust convert into a haphazard walking tour the life of a boy and then a man up till the age of 35; and what then?

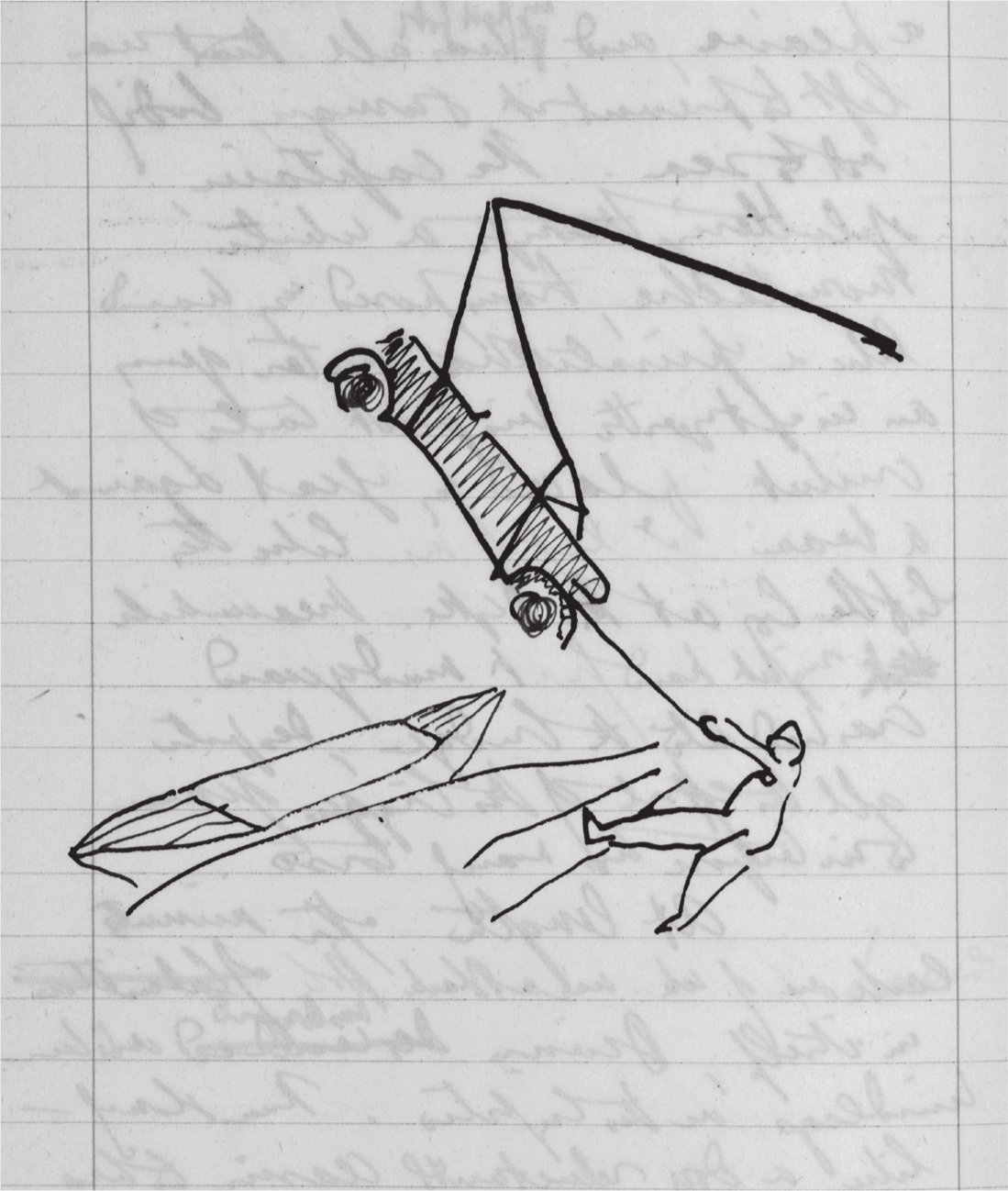

They drank about half a bottle of wine each, and this began to affect their demeanour. Fleischmann, with excusable pride,

produced his stick, proportioned like an ogre’s club. Beneath the knotted handle lay a silver shield embedded in a pointed wreath of bay leaves of the same metal, bearing an inscription of Gothic congratulation and good wishes for the round-

the-world

trip. The body of the stick was covered with deeply incised names, in all varieties of lettering and alignment. These appeared to be relics of the old Heidelberg days – the

Trinknamen

of the other members of the drinking-corps of which Fleischmann had been a member. Fleischmann’s own had been

‘Apollon’

he begged us to note.

On Schwert’s stick, which was less like the bole of a giant oak, there were three names only. It was not difficult to visualize how popular Fleischmann had been, how mediocre the devoted Schwert. The couple reproduced many of the more commonplace aspects of the English public school.

They told us of their experiences in Albania. The Mpret or Governor of the country, a bishop, lately a waiter in New York, had at one period of his life had an injured arm cured in Vienna. The Germans had, therefore, pretended that they were Viennese; with the result that he had taken them under his wing and finally presented them with souvenir

cigarette-holders

, multi-coloured and square in shape, an inch broad, half-an-inch deep and four long. Of these they were forgiveably proud, smoking Simon’s cigarettes with avidity. The Governor, they said, went about armed to the teeth.

Meanwhile more wine had disappeared. Though from all accounts a German university drinking-corps teaches its members to consume as much alcohol in an evening as a modern mother at a dinner table, the formality of our party began to dissolve. They started to play upon a mouth-organ and sing. Fleischman, infinitely the louder of the two, was neither in time nor tune. Schwert had a good voice and some technique. They sang mainly war songs:

‘Der Wacht am Rhein’

, and an anti-French ditty which delighted Simon, and made me angry. But the epic of the evening was a long-drawn ballad about a mother visiting her son in hospital and the son’s

eventual decease. This would have wrung tears from a stone in 1917. Even on the waters of Greece in 1925 we became thoughtful and serious; though the dramatic intensity with which it was rendered, would, in any case, have necessitated a demonstration of genuine and profound feeling. An elderly Greek asleep in a corner remained entirely unaffected, both by the sentiment and the noise.

The evening ended about one o’clock, after our having vindicated the Union Jack with ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ on the ship’s tin piano. The Germans went out to curl up in our deck-chairs; we to our cabin-de-luxe, whence I retired to the dining-room. The cows were getting restless, and sleep did not come easily.

Such is the Youth movement in so far as it was brought to our notice. Both Schwert and Fleischmann became eventually very confidential, and the above facts are substantially true. Whether they are interesting I hesitate to say. Perhaps in days to come, the memory of this couple of young men, floating fortuitously over the surface of the earth, will serve to recall not only the miserable tragedy of a European war, but also the unsettled mentalities and bitter disappointments created by the Peace that followed.

AT FOUR O’CLOCK ON THE MORNING

of Saturday, September 5th, the lights of Patras twinkled out of a rather muddy dawn, as the

Iperoki

glided into the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth. To our alarm, instead of mooring up alongside the quay, she dropped anchor 400 yards out to sea; and was immediately surrounded by a swarm of rowing boats anxious to disembark passengers. There followed one small lighter. What was to happen to Diana?

As the darkness disappeared and the mountain-tops began to take shape above the motionless surface of the water and the faintly distinguishable outline of the town, the black form of a larger lighter became apparent, moving silently towards us. This possessed a small deck at either end, perched above an uncovered hold in the middle. Gradually she drew up against the

Iperoki

. With the aid of the derricks the hold was first filled with barrels. Then the crew, joined by a host of swarthy stevedores, turned their attention to Diana. Fortunately the ropes by which she had been embarked had not been removed; and a second hour’s argument was thereby saved. David and Simon were not present – or if they were, only in the manner of a harem, seeing but invisible. The Germans elbowed their way about, anxious to display their efficiency and make sure of their ride to Athens.

A fiery altercation ensued over the two pieces of wood that the Germans and I insisted should be inserted between each of the pairs of lifting ropes, in order to prevent their crushing the sides of the car. After an infinite variety of abuse and persuasion, two heavy beam-like boards were lifted from the

roof of the

Iperoki

’s hold and appropriated to the purpose, leaving two yawning cavities in the main deck. The derricks creaked. Shivering all over, Diana, like an unwilling bull, was raised slowly by the nose, and continued thus until she was hanging at an angle of 60 degrees to the horizontal. With a heave, her hind wheels rose up on to the roof of the hold. There was a crash. One wheel had fallen into the slot left by the absent board, and the car came down heavily on the petrol tank, back light and luggage carrier. The Germans, assuming the postures of a platoon caught by a modern sculptor in its own barbed wire, flung themselves beneath Diana’s body, straining every particle of their beings, muscles a-quiver, veins standing in relief. Sweat dripped from their foreheads. Paralysed by the horror of the moment, I was keeping aimless hold upon a rope attached to the luggage carrier, when, with a desperate spasm, the car rose again and threatened to swing right out over the sea. All that was to prevent it was the rope of which I was unwittingly letting go. The captain, choking like a master of foxhounds, seized my hands and transposed them after the fashion of a schoolmaster giving an inept youth his first taste of cricket. My feet he jammed against a beam. I was left like the little boy at the dyke, clinging like grim death to my rope, as the car swung helplessly in the air. Finally the off front mudguard crashed heavily into the bridge, despite the heroic efforts of Fleischmann to interpose his torso as a buffer.

At length, after minutes of suffocating suspense, Diana’s hind wheels descended upon one of the lighter’s decks. Then, very slowly, in the manner of a dog reluctantly ceasing to beg a lump of sugar from an obdurate mistress, the front wheels were lowered also. By some miraculous good fortune they, too, landed on the lighter. Faithful to the end, the Germans clambered down with them, while we went off with luggage and coats in a rowing boat, leaving the spare tyres on board.

Landing without having had our passports examined, we walked up to the customs house and presented the

douanier

with a letter from the Greek Minister in London. The effect was magical. Wreathed in smiles, the official waved our luggage past on the back of a remarkably active old woman, assuring us meanwhile that no difficulty would be made about the entry of the car into the country. There remained, however, to translate it to dry land. We marched in a procession down to the quay where the lighter was expected, the luggage on a hand-cart bringing up the rear.

No sooner had we reached the quay, than the luggage, which we had placed in charge of a small, peaky interpreter, vanished. Simon went in search of it in one direction, I in another. Then David disappeared as well. After a second exploration, I came back to find the interpreter resurrected, having deposited the trunks at his office. David and Simon were nowhere to be seen. Then the lighter arrived. Other schooners had to be moved. Eventually three rough-hewn boards, cracked with age and flaking with decay, were flung casually from the shore to the car. The Germans heaved, their countenances contorted with righteous exaltation. A crowd of loafers, half naked beneath a fog of rags, pushed with them. Up over the parapet of the lighter the tyres moved, then slowly down the creaking bridge and on to dry land once more. David returned; the engine started; with one triumphant bound Diana leapt like a gazelle up on to the promenade; then stopped with a grunt, from lack of petrol. A large crowd collected, from the depths of which the chief stevedore and the shipping company’s agent clamoured for money. When petrol had been provided, we went off to the main hotel, which consisted superficially of no more than a door and a passage, and ordered breakfast in a café outside it.

Patras is a town sloping up a hill from the sea, at right angles to the quay-side. The streets cross and re-cross also at right angles. The buildings are all of that indefinable age and style that pervades the modern East – ‘East’ inasmuch as the Greeks invariably refer to their partners in western civilization as ‘Europeans’, using the word as a term of distinction. The main streets are arcaded. The stucco peels, without conveying an impression of antiquity. Most of the houses are characterless boxes.

As we waited for our breakfast, the sun gradually dispelled the early morning haze, and began to throw the shadows of the buildings upon the mud of the lately-watered roads. Looking down the main street to the harbour, the Gulf of Corinth was visible through a web of masts and rigging. The ships lay at anchor in hundreds, all brightly painted, in brilliant

contrast to the piercing blue of the Grecian sea-blue into the depths, unlike the flat turquoise of the Italian waters. While beyond, rose the high range of mountains that embattle the further shore throughout the whole eighty miles of the Gulf, with wisps of misty cloud wreathing round their peaks like scattered thistledown.

Even at this early hour the streets were full of people, picking their way through the slush created by the

water-cart

. The modern Greek is of less than ordinary height, delicately made, and, at first sight, undistinguished. Both men and women, though seldom repulsive, appear mediocre and perhaps dirty. Then, on second view, the traditional type of the ancient Greek statue is often apparent, beneath a

thickly-plaited

straw hat and a small black subaltern moustache. The girls, though for the most part commonplace, are sometimes of great beauty, with nose and forehead forming an unbroken line, smooth brown skins, sensitive plum-coloured lips, and proud, rounded chins. The priests seem to tower above their fellows, upright commanding figures with long chiselled Byzantine noses and dark eyes flashing beneath their black cylindrical hats, rimmed at the top, their beards flowing down to their pectoral crosses, and their hair neatly screwed into grizzled buns behind.

The fustanella, despite its association with the Victorian geography book and the oft-told epics of pre-Victorian Liberty, is still commonly worn among the peasants. There is a certain unreality about any form of national dress, when seen for the first time in actual everyday wear. One recalls the meticulous horrors of some Turkish massacre, purchased by one’s great-great-aunt, from the Royal Academy of 1833. Or some faded photograph of a fancy dress ball in the seventies springs to the mind from out its gilt-bevelled cardboard archway. However, as we spread our tinned jam upon our rounds of dry bread, the dirt and squalor of the old men who passed by, their short tunic skirts either black or white, frilling out above their knees and their whole legs swathed in bulky

white wrappings tied here and there like parcels of washing, belied any suggestion of self-conscious picturesqueness. There does exist, as a matter of fact a Society for the Preservation of National Costume. It has its representative in each town. But he struts about in full ceremonials, his white jacket elaborately embroidered in black, and a red fez seated on his head, from which depends a tassel that reaches to the small of the back. This has little connection with the ordinary utility dress. The shoes are large and flat, like barges, turning up at the toes, on which are perched immense black bobbles.

Thus we sat at small rickety iron tables upon the pavement in Patras, a prey to the fact that we were in Greece, when up walked two persons. The first was Mr Constantinopoulos, born at Salford, in Devonshire, the secretary of the local British consulate. He was dressed in white linen, and long flowing white moustaches projected on either side of his burned, haggard face. Simon, before discovering his name, informed us that his pronunciation was lowland Scottish. His English was colloquially Edwardian. He assured us that not only was there no road from Patras to Athens, but not even so much as a path.

The other newcomer was destined to play a larger part in our day. His name was Christian Teeling, and he had been born and educated at Dulwich. A small man, youngish and bald, with rimless pince-nez, he elbowed his way out of the crowd, and addressed himself to us in a voice of breeding and education.

‘I see that you are countrymen of mine,’ he said. ‘Believe me, I shall be only too gratified to render you any small assistance that may lie within my power.’

He assured us that in these out-of-the-way parts a strange face, especially an English one, was always welcome. He was of the opinion that there might possibly be a road to Athens. He would fetch a naval survey of 1912, which would tell us for certain.

Meanwhile we drank our coffee. The Germans were ravenous and swallowed all the milk out of the jugs. Some distance away, at the top of the street, stood a castle on a high hill. Opposite, across the road, the shell of the old cinema, burnt down in the

exuberance of the April carnival, remained. Posters of six months ago, advertising ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’, clung sadly to their boards. Mr Teeling soon returned. After consultation with everyone of his acquaintance, he was forced to confirm the forebodings of Mr Constantinopoulos. The survey of 1912, which he had very kindly fetched, supported him. There literally did not exist a road from Patras to Athens. The mountains shelved straight into the sea and the railway ran along a ledge cut from their face. Could we drive along the railway? Unfortunately the ravines were only crossed by trestle bridges. Besides, what course should we pursue in the eventuality of a train coming in the opposite direction? From Corinth to the capital the road was excellent.

Reluctantly, therefore, we decided to put the car on the train. The interpreter, in league with the hotel, discovered that we could not obtain a waggon that day. So we booked some bedrooms, brought out the Keatings, and with a ‘so long’ from Mr Teeling, who was a schoolmaster and had to be off to his class, set out to bathe.

The sun was now blazing at its height. With the Germans in the back, we drove some five miles along the road to the west. Then, since it turned off into the mountains, came back a little way. After some discussion we discovered a small strip of beach overspread with matted but sharp-leaved seaweed and screened from the drowsily-moving carts on the road by a row of maize. Why is it that maize is never grown in more than one row? The Germans produced red bathing dresses from their packs. Leaving our clothes in heaps upon the edge of the grass, we ran down into the water. After walking twenty yards over the tortuous weeds, the bottom suddenly went from under our feet, and we were swimming gaily about the spot where the battle of Lepanto was fought.

There is a unique rapture about a Greek bathe. The mystery of Ancient Greece unfolds itself. Those petty wars, those city states! Those burdens of the classroom! And now, lying back and blinking at the sky, defying the sun from the cool shadows

beneath the surface, the endless succession of mountain tops, the foothills, half brown, and the scrubby olive trees, rocks and patches of cultivation, all combined to reveal the enigma of that legendary country, where Europeanism evolved in miniature and for whose sake men of all ages, ranks and riches, have sacrificed their lives in gratitude for their inheritance. The very air inspires a feeling of nobility.

We returned in time for lunch. I had trod on a sea urchin, and was obliged to assume a Byronic limp. Mr Teeling met us. The meal, which was served in a fly-blown restaurant with heavy, red plush curtains drooping round its windows, lasted from two to three hours. It was too hot to move. Mr Teeling informed us that, unfortunately, his wife was in the old country at the moment, else she could have entertained us. His quarters were limited owing to financial embarrassment resulting from his having started his career under the auspices of a Venizelist Government. Nevertheless could we bring ourselves to take tea with him? He had some roseleaf jam.